‘France est de la retour,’ declared its new, powerful prime minister Édouard Philippe last week. ‘France is back.’![]()

Ultimately, it wasn’t the coming of a new ‘Sixth Republic.’ Nor was it unprecedented in the political history of the Fifth Republic, nor did it exactly herald the death knell of France’s established political parties.

But the June 18 victory of French president Emmanuel Macron’s La République En Marche! — a party founded only last year as the vehicle boosting what was once a longshot bid for the French presidency — in the second round of France’s legislative elections is nothing short of an astonishing accomplishment for a brand-new party that brands itself as neither left nor right.

The elections leave Macron’s party, together with its ally, the Mouvement démocrate (Democratic Movement) founded by longtime centrist figure (and now Macron’s justice minister) François Bayrou, with 350 seats in the Assemblée nationale, the lower house of the French parliament. It’s one of the largest majorities since the dawn of France’s Fifth Republic in 1958, though it’s a victory tarred by a record-low turnout of just between 42% and 43%. (That compares to around 60% turnout in 2007 and 55% in 2012).

While the French electorate may be fatigued after four rounds of voting — two presidential rounds in April and May, followed by the first round of parliamentary elections on June 11 — it’s far lower than turnout in the 2002, 2007 and 2012 elections, all of which followed the same pattern, synchronizing legislative elections just a month after the presidential.

The most important lesson for Macron is that, while the French electorate is giving him a green light to push forward with aggressive plans to shake up the public sector, it’s not an irrevocable grant, given the depressed turnout.

Macron’s accomplishment isn’t unprecedented, it’s just unprecedented for such a nascent movement in French political life. It gives Macron and his government, headed by Édouard Philippe, the 46-year-old prime minister who previously served as mayor of Le Havre (on the Norman coast) since 2010 and an ally of former prime minister and foreign minister Alain Juppé. Unlike Macron, who previously served in François Hollande’s administration as an economy minister and a former member of the center-left Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party), Philippe was until his appointment a member of the center-right Les Republicaíns and a prodigy of former foreign minister and prime minister Alain Juppé. Together with a handpicked set of ministers from the center, the center-left and the center-right, Macron and Philippe have a good chance at introducing the reforms that Macron (and many of his predecessors) have long promoted, starting with legislation to liberalize the French labor market.

Macron’s 350-seat majority, smaller than projections of up to 455 seats is still larger than typical. But it isn’t so far outside political tradition, and that’s a healthy reminder for Macron not to take for granted his political invincibility. Since 2002, the French electorate has granted recently elected presidents a strong working majority in ensuing parliamentary elections, avoiding the messy cohabitation governments of the 1980s and 1990s.

After Hollande’s narrow presidential victory in 2012, the Socialists won 258 seats (compared to REM’s 308 this year), and with their allies, they commanded 306 seats (compared to 350 this year). But those Socialist MPs owed little to Hollande, an unlikely president who emerged as a weak consensus choice when former IMF managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn’s candidacy imploded after allegations that he sexually assaulted a hotel maid. Today, many of the newly elected En marche MPs are neophytes to politics and owe their careers to Macron, aides carefully chose who would run under the REM banner.

Nevertheless, in 2007, Nicolas Sarkozy’s center-right party won 313 seats and, with their allies, commanded 345 seats, just about the same margin that Macron will enjoy. And after Jacques Chirac won reelection against the Front national‘s Jean-Marie Le Pen in a veritable landslide in 2002, the center-right and its allies commanded 399 seats.

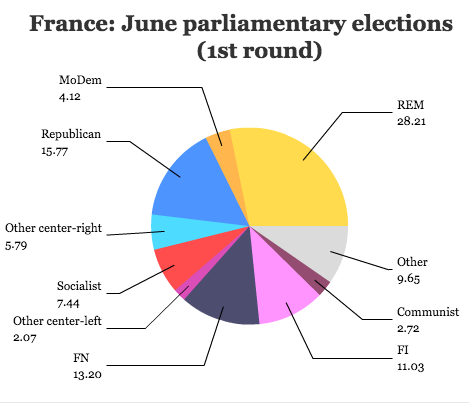

Moreover, in the first round of the parliamentary elections last week, Macron and his allies together won around 32.3% of the vote, while around 21.6% for the center-right Republicans and their allies. The outgoing Socialists and their allies won 9.5%, while presidential runner-up Marine Le Pen and the Front national won 13.2%, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s left-wing La France insoumise (‘Unsubmissive France’) won 11.0%. Those results, if anything, show that the French electorate, aside from record-high numbers who chose not to take part, divides deeply and widely on political views that run from the deeply eurosceptic to deeply enthusiastic about European integration, from hard-right xenophobia to hard-left socialism.

As Macron and his aides hope to project a ‘Jupiterian’ stance for a more dignified presidency that’s cool, regal and removed from the cut-and-thrust of daily politics, Macron risks projecting disinterest, detachment and haughtiness. In five years’ time, Macron’s En marche could evaporate with as much velocity as it arrived. That might restore the established parties, however reformed; it might facilitate way for a Le Pen resurgence. However impressive Macron’s 2017 has been, he’ll have five long years to fall from the grace of some very lofty expectations.

For now, though, Macron’s honeymoon continues.

In an election season that ended the careers of two former presidents (Sarkozy and Hollande) and two former prime ministers (Juppé and François Fillon), it’s not surprising that two rounds of parliamentary elections also vanquished other long-term fixtures of French politics. Republicans saw the defeat of a rising star in former environmental minister and Paris mayoral candidate Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet (known in France simply by her initials, ‘NKM’). Socialists saw the defeat of former education minister Benoît Hamon, their 2017 presidential nominee, as well as party leader Jean-Christophe Cambadelis, who promptly resigned on Sunday.

Former prime minister Manuel Valls, a centrist who lost the Socialist presidential nomination to Hamon in January, nearly lost his own seat to a far-left candidate in his own seat in Essonne’s 1st district. While Macron’s centrist En marche rejected Valls’s hopes to become a candidate for REM last month, it also extended Valls the rare courtesy of not running an En marche candidate against him; Valls still struggled to win his seat, so tarnished is his legacy after nearly three fruitless years as Hollande’s prime minister.

The new REM legislators represent a generational and cultural sea change, and their election will result in a National Assembly with a record-high 233 female deputies (nearly 39% of the entire National Assembly) and that’s, on average, 10 years younger. They include Hervé Berville, a 27-year old economist who was born in Rwanda, survived the genocide and was adopted into a family in Brittany. They also include the 43-year-old Cédric Villani, a foppish dandy known for his spider brooches and eccentric neckware, who also happens to be a brilliant mathematician who won the Fields Prize in his mid-30s.

While the traditional parties weren’t quite annihilated, as some projections suggested, there’s no doubt that the Socialist Party lies in shambles after five years of a president in Hollande whose approval rating plummeted to single digits and whose presidential candidate won just 6.4% of the first-round vote. Mélenchon, who won a seat from the 4th district of the Bouches-du-Rhône constituency, will be thrilled that his movement won 17 seats, and that the Parti communiste français (PCF, French Communist Party) won an additional 10 seats.

But the lesson of the 2017 elections for the French left, at every level, is that it must unite or die. Had Hamon dropped out and endorsed Mélenchon in the first round, and had Hamon’s voters backed Mélenchon, the leftist would have placed first (nearly 2% higher than Macron) and waged a far more competitive runoff campaign against Macron than Le Pen. In the legislative elections, even more incomprehensibly, the French left split into four camps — what’s left of the Socialists and their allies, the Mélenchon hard-left, the Communists and the Green/Ecologists. That means that many leftist candidates lost in the first round and never made it to the June 18 runoffs. Unless the four camps can find some common ground in the future under a common leader, there’s virtually no chance that they can hope to win power in 2022. With so many high-profile Socialists eliminated, that role may now fall by default to the fiery, outspoken 65-year-old Mélenchon.

Marine Le Pen, too, faces an uncertain future. Although she won her race in 11th district of the northeastern Pas-de-Calais constituency, her party won just eight seats nationally — more than at any time since 1986, but still something of a letdown. Adding to her unexpected low runoff support (33.9%) and her unsteady performance in the presidential debate against Macron, she will face questions about her leadership going forward and her judgment in running such a stridently anti-Europe campaign that called for a referendum on withdrawing not only from the single currency but from the European Union altogether. Marion Marechal-Le Pen, Marine’s 27-year-old niece, didn’t even attempt to win reelection from her southern French seat, and Florian Philippot, a leading Le Pen aide who engineered the FN’s eurosceptic program, lost his race.

Lost in the Macron wave? The nationalist Pè a Corsica (For Corsica) won three of Corsica’s four seats in the National Assembly, reflecting gains from local elections in recent years.

The Republicans, meanwhile, will constitute the largest opposition force in the next National Assembly. Perhaps the most important lesson for the French center-right is not to nominate a presidential candidate (in Fillon) who’s undergoing indictment for a corruption scandal in real time, thereby conceding a presidential race that had been the center-right’s to lose.

If there’s one silver lining, it’s the campaign of that former budget minister François Baroin, a Sarkozy acolyte. Though Republicans briefly hoped to win the largest bloc of seats in the National Assembly, the party’s 113 seats far outshines the Socialists and exceeded expectations. While Baroin failed to convince Philippe and Bruno Le Maire, now economy minister, to leave the party, he convinced many others, like NKM, to contest seats as Republicans instead of defecting to Macron. The next five years will likely feature the same fights of the last five — a reform-minded center-right (personified by Baroin, Juppé, NKM and others) that will be eager to support Macron’s liberalizing efforts versus a cultural right that hopes to win back Front national voters by emphasizing immigration, terrorism and socially conservative values (personified by Laurent Wauquiez). The problem for Baroin is that with so many of the reform camp’s former leaders now taking starring roles in the Macron government (like Le Maire and Philippe), the only way for the Republicans to differentiate themselves is by pulling hard to the right, especially with a sense that the failure of Le Pen and her brand of hard-right populism might give Republicans an opportunity to win many of those FN voters.

“That might restore the established parties, however reformed; it might facilitate way for a Le Pen resurgence”

I disagree that https://mikelangcinevariety.wordpress.com/cine-variety-memories-of-a-forgotten-era/

Mitzie