There’s no way for the German left to sugarcoat Sunday’s regional election result in North Rhine-Westphalia.

![]()

It’s the clearest sign yet that after flirting with Martin Schulz earlier this year, German voters are coming back to Angela Merkel and the center-right Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union).

North Rhine-Westphalia is Germany’s most populous state, and it’s one of the industrial and technological heartlands of Europe. It’s a relatively left-leaning state — since 1966, the only CDU leader to run the state’s government was Jürgen Rüttgers, from 2005 to 2010. Moreover, it’s the state where Schulz, the SPD’s chancellor candidate for this September’s federal elections, grew up. It’s home to 17.8 million of Germany’s 82 million-plus population. So four months before the national election, NRW has as more predictive power than you might typically expect for a state election, considering that its electorate equals just over one-fifth of the electorate that will decide the national government in September.

It’s too soon to guarantee that Merkel will win a fourth consecutive term, even with the decisive victory last weekend — the third and most important CDU win in three state elections this year. But the result is a clear sign that Schulz’s center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) is struggling to connect with working-class voters who are turning increasingly to alternatives from the anti-immigrant right to the protectionist left to the reassuring stability of the Merkel-era CDU. Indeed, the CDU campaigned throughout the spring on the notion that Merkel and her allies amounted to a ‘safe pair of hands.’

Schulz had campaigned hard in North Rhine-Westphalia, arguing that if the SPD were to win reelection in the state, it would show that Schulz was on the path to election as chancellor. The loss is a bitter pill for a party that hoped Schulz’s emergence would end 15 years stuck in opposition or the purgatory of serving as the junior partner to Merkel in two periods of Große Koalition since 2005. Even as Schulz has called for rolling back part of the landmark labor reforms put into place by the last SPD chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, in the early 2000s, his slightly more populist brand of pro-European social democracy hasn’t managed to keep enough working-class Germans.

Even more devastating for the SPD is the loss of Hannelore Kraft, the talented minister-president who ran the state’s government since 2010 and who won a decisive victory in the 2012 election. Though she routinely declaimed any interest in running for chancellors, polls showed that in 2013 (as well as in 2017), Kraft was one of the most popular figures within the Social Democratic Party. She promptly resigned as the head of the state party, and her defeat will be a sharp loss of one of the SPD’s most dynamic figures who might have played an important role in a future Schulz chancellorship. Kraft, over seven years, developed a record as a capable administrator and a neo-Keynesian counterpart to Merkel’s more austere approach to fiscal policy.

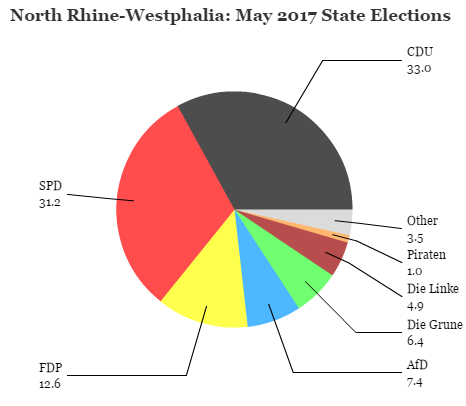

The result leaves no party with an absolute majority in the 199-seat Landtag, the state’s legislative assembly. Economic liberals, however, will be encouraged by the stronger-than-expected performance of the center-right liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democrats), who won 28 seats — just enough to give the two parties a majority coalition.

Under the 38-year-old Christian Lindner, a Düsseldorf resident who heads both the national party and the local FDP in North Rhine-Westphalia, the Free Democrats expect to return to the Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament, this September. In 2013, the party narrowly fell below 5% support, leaving the FDP with no federal representation for the first time in the postwar era. If the FDP succeeds, Lindner might well become the next vice-chancellor or foreign minister. The CDU and FDP governed in a national coalition during Merkel’s second term from 2009 to 2013.

In any event, Armin Laschet, a former state minister in the last CDU-led government in North Rhine-Westphalia, is expected to form the next government — either in a CDU-FDP coalition or a ‘grand coalition’ with the SPD.

The SPD’s defeat is the third of three state election defeats this spring. It followed a defeat in the state election in Saarland on March 26, when the CDU won 40.7% of the vote to just 29.6% for the SPD. (The Greens, at 4%, lost all of their seats.) It also follows a CDU victory in the far-northern state of Schleswig-Holstein on May 7, where minister-president Torsten Albig and his SPD-led coalition lost power; the CDU defeated the SPD by a margin of 32.0% to 27.2%.

It was easy enough to blow aside the CDU victory in the smaller Saarland, a traditional CDU heartland, and even the Schleswig-Holstein result, with its smaller population. Schulz and the SPD, however, will not be able to deflect the clear message that the NRW result sends.

In February, foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel (then economy minister) withdrew from consideration to lead the SPD in the 2017 elections. That paved the way for the more popular Schulz, who promptly resigned as an MEP, the leader of the EU-wide Socialists and Democrats group (since 2004) and president of the European Parliament (since 2012). Schulz, viewed as a slightly more populist figure in touch with the working class, never served as a minister in any of Merkel’s CDU-SPD ‘grand coalitions,’ unlike Gabriel and the previous two SPD chancellor candidates.

Almost immediately after the announcement, Schulz and the SPD were tied in the polls with the CDU. Over the last three months, however, Merkel’s CDU has calmly retaken the lead. The latest YouGov poll, from May 8 to 11, shows the CDU leading the SPD by a margin of 37% to 25%.

Though Germans might have initially viewed Schulz as a safe choice for change, they are now returning to Merkel, in office for 12 years and running, a champion of pro-European, pro-immigration liberal democracy. In an era of Brexit and Donald Trump, Merkel may be benefiting from the sense that she is an experienced hand in a world that’s suddenly far more unstable than it appeared even a year ago. Though Schulz has four months to repair his party’s standing, Merkel — like Emmanuel Macron, the new French president — is now winning voters for her strong pro-migrant, pro-EU views, the liberal backlash to the rise of xenophobic nationalism across much of the developed world. Whereas Merkel seemed like she could suffer mightily for her 2015 decision to welcome a million migrants into Germany, especially after the Cologne violence on New Year’s Eve 2015, voters are instead flocking to Merkel as a focal point for stability, even in North Rhine-Westphalia, which took in more migrants than any other German state.

The SPD’s traditional ally, Die Grünen (the Green Party), is struggling even more, coming dangerously close to falling below the 5% threshold to win seats in the Landtag. That’s an embarrassing result, and it too is ominous for the autumn federal election. In aggregate, NRW voters swung away from the SPD and the Greens by 12.8% since the last election in 2012. Even at the higher polling numbers it boasted earlier this winter, the SPD will be hard-pressed to form a government if Green support plummets the way that it did in North Rhine-Westphalia.

Part of the SPD’s traditional support seems to have drained away to the eurosceptic and anti-migrant Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany). Though the AfD is down in national polling from a high of 15% last summer to around 8% to 10% today, it won 7.4% of the vote in the North Rhine-Westphalia election — still enough to make it the fourth-largest block in the Landtag. Exit polls suggested that AfD supporters were more likely to come at the SPD’s loss than the CDU’s.

The democratic socialist Die Linke (Left Party) doubled its support from 2012, though it fell just below the 5% threshold. Meanwhile, the Piraten, a group of disparate activists who support direct democracy and intellectual property reform, have fallen out of the Landtag altogether, losing the 17 seats they had won in 2012. Though a popular movement in various northern European countries in the early 2010s, the ‘Pirate’ movement has lost support everywhere except Iceland, where it holds 10 out of 63 seats in the national parliament.