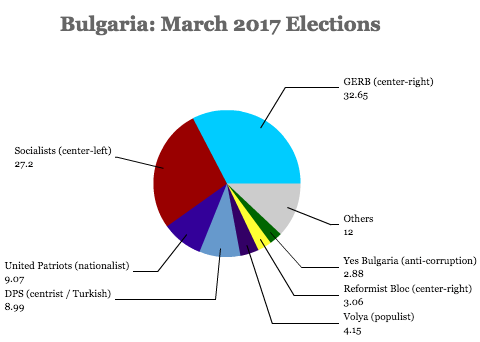

It’s been nearly two-and-a-half years since the last election, but Bulgarian prime minister Boyko Borissov’s center-right party won just about the same percentage of the vote that it did in 2014 — around 32.7%. ![]()

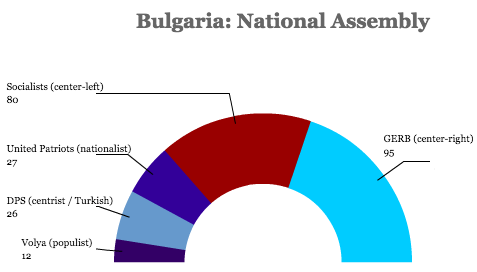

That performance was good enough for an 11-seat increase in the National Assembly (Народно събрание), making Borissov more likely than not to retain the premiership. It’s a remarkable turnaround after Borissov, dogged by allegations of corruption within his government and after his party suffered a humiliating defeat in last November’s presidential election, resigned earlier this year and triggered snap elections.

If he can form a governing coalition, it would be Borissov’s third non-consecutive stint as prime minister, his first coming in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2009. At a time when Russian president Vladimir Putin is working to undermine European democracy, top European leaders and EU officials alike view Borissov as a soothing center-right ally firmly devoted to European integration. EU leaders will certainly far prefer a Borissov government with Bulgaria set (for the first time) to assume the six-month rotating EU presidency in early 2018.

As both an EU and NATO member, Bulgaria is a key ally on the eastern periphery of the European continent. It’s a northern neighbor of the economically depressed Greece and the increasingly autocratic Turkey and just across the Black Sea lies a divided Ukraine and Russian-annexed Crimea. These days, it’s an increasingly tough neighborhood. Despite European anxieties about reliance on Russian natural gas, Borissov last year was already considering the resurrection of the on-again, off-again South Stream gas pipeline from Russia (talks began in 2006, but ended after Borissov won the 2014 election), even as the country’s new president called for better relations with Russia. While the number of ethnic Russians in Bulgaria is negligible (far less than ethnic Turks, which comprise nearly 9% of the population), a large majority of Bulgarians belong to the Orthodox church, sharing important cultural touchstones with Russia.

Earlier this year, voters seemed likely to punish his party, the center-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, Граждани за европейско развитие на България) for years of economic malaise and widespread corruption. GERB’s presidential candidate last November, Tsetska Tsacheva, the former chair of the National Assembly, lost a second-round runoff by a 23% margin to Rumen Radev, an independent and former Bulgarian Air Force commander endorsed by Bulgaria’s center-left.

At the time, coming days after Donald Trump’s successful, if once implausible US presidential campaign, Radev’s victory was yet another incremental geopolitical victory for Russian president Vladimir Putin, given Radev’s call for closer ties with Russia. Indeed, Tsacheva’s defeat was the proximate cause for Borissov’s resignation.

Instead, after the March 26 elections, GERB won 95 seats, the largest bloc in the National Assembly.

The center-left Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP, Българска социалистическа партия) improved on its dismal performances of the last eight years, increasing its representation in the National Assembly by a whopping 41 seats. But its leader Kornelia Ninova must be disappointed in what last November seemed like it would be an easy win. Indeed, throughout the campaign, the BSP had more momentum than GERB.

The 48-year-old Ninova invigorated voters with a healthy dose of populism and nationalism, blasting EU officials for treating Bulgaria like a ‘second-class’ member and welcoming closer ties with Russia (far stronger than anything the BSP-backed Radev promoted either as candidate or as president), including a veto on EU sanctions against Moscow.

A week ago, Ninova had hopes of forming a new government and firmly ending the Borissov era. Now, she has to decide whether the Bulgarian Socialists will (once again) remain in the opposition, provide support to a ‘grand coalition’ government with Borissov and GERB or find a way to form an even more implausible government of her own.

With his former centrist ally, the Reformist Bloc (Реформаторски блок) falling below the 4% electoral threshold, Borissov has few good choices to find a parliamentary majority. A new anti-corruption party, Yes Bulgaria (Да, България!) formed in January by former Borissov justice minister Hristo Ivanov fared even worse than the Reformist Bloc. That’s despite Bulgaria’s abysmal record, which ranks worst in the European Union. Per the 2016 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, Bulgaria ranked 75th worldwide (compared to just 57th for neighboring Romania, which entered the European Union at the same time, and comparable to 75th-ranked Turkey and Tunisia or 79-ranked Belarus, Brazil, China and India).

Though Ninova has ruled out a grand coalition, it remains by far the best option for a stable long-term Bulgarian government. The only remaining parties include the Turkish-interest Movement for Rights and Freedoms (Движение за права и свободи) and two new nationalist and eurosceptic parties, the largest of which is United Patriots (Обединени Патриоти), an alliance formed last year among three parties, all of which are traditionally conservative, populist, protectionist, eurosceptic and anti-Islamic. Tension between anti-Muslim nationalists and Turkish Bulgarians were common in the lead-up to the vote. That makes a coalition with ethnic Turks and nationalists farfetched. Perhaps the likeliest outcome, if least fulfilling, is a minority Borissov-led government with outside support from the nationalist parties or a formal coalition.

Though it’s more likely that the nationalists will use Ninova for leverage, there’s a chance that she might wind up leading a vaguely populist and economically nationalist government herself. Both the Bulgarian Socialists and many of the Bulgarian nationalists share ties to the Orthodox Church. Beyond better ties with Russia, Ninova hopes to replace the country’s 10% flat tax with a more progressive rate and hopes to derail the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) that’s approaching finalization. It’s a result that would cause fits in Berlin and Brussels, smiles in Moscow and perhaps some delight in Washington — that is, if the Trump administration even has a foreign policy in respect of Bulgaria.

The country has faced difficulties in the decade since joining the European Union. EU accession, in some ways, is exacerbating long-established and ominous trends for a country in economic and demographic decline. In just three decades, the country’s population has dropped from 9 million to barely 7 million as the country’s more ambitious head for Berlin, Frankfurt, Milano or (for now, at least) London. Between 1996 and 2007, the date of Bulgaria’s EU accession, its per-capita GDP rose from around $1,200 to $5,900 as the country emerged from Soviet-era communism. But GDP growth stalled after the 2008-09 financial crisis and 2010 eurozone crisis and today, GDP per capita is still depressed from its highs earlier this decade (around $7,000 in 2015), and Bulgaria remains the poorest member-state of the European Union.

If he forms a goverment, Borissov will have a rare third chance to implement the kind of reforms he has long pledged to reduce corruption and boost employment, pensions and the economy more generally.

One thought on “Bulgaria’s Borissov (and EU) gets reprieve from dissatisfied voters”