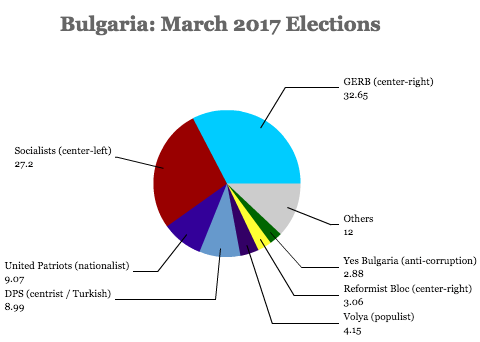

It’s been nearly two-and-a-half years since the last election, but Bulgarian prime minister Boyko Borissov’s center-right party won just about the same percentage of the vote that it did in 2014 — around 32.7%. ![]()

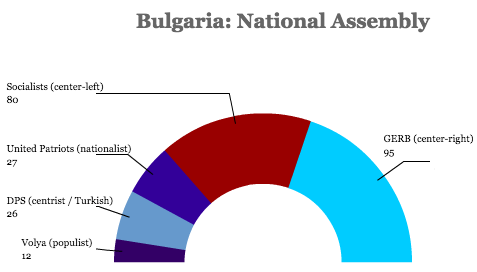

That performance was good enough for an 11-seat increase in the National Assembly (Народно събрание), making Borissov more likely than not to retain the premiership. It’s a remarkable turnaround after Borissov, dogged by allegations of corruption within his government and after his party suffered a humiliating defeat in last November’s presidential election, resigned earlier this year and triggered snap elections.

If he can form a governing coalition, it would be Borissov’s third non-consecutive stint as prime minister, his first coming in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2009. At a time when Russian president Vladimir Putin is working to undermine European democracy, top European leaders and EU officials alike view Borissov as a soothing center-right ally firmly devoted to European integration. EU leaders will certainly far prefer a Borissov government with Bulgaria set (for the first time) to assume the six-month rotating EU presidency in early 2018.

As both an EU and NATO member, Bulgaria is a key ally on the eastern periphery of the European continent. It’s a northern neighbor of the economically depressed Greece and the increasingly autocratic Turkey and just across the Black Sea lies a divided Ukraine and Russian-annexed Crimea. These days, it’s an increasingly tough neighborhood. Despite European anxieties about reliance on Russian natural gas, Borissov last year was already considering the resurrection of the on-again, off-again South Stream gas pipeline from Russia (talks began in 2006, but ended after Borissov won the 2014 election), even as the country’s new president called for better relations with Russia. While the number of ethnic Russians in Bulgaria is negligible (far less than ethnic Turks, which comprise nearly 9% of the population), a large majority of Bulgarians belong to the Orthodox church, sharing important cultural touchstones with Russia.

Earlier this year, voters seemed likely to punish his party, the center-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, Граждани за европейско развитие на България) for years of economic malaise and widespread corruption. GERB’s presidential candidate last November, Tsetska Tsacheva, the former chair of the National Assembly, lost a second-round runoff by a 23% margin to Rumen Radev, an independent and former Bulgarian Air Force commander endorsed by Bulgaria’s center-left.

At the time, coming days after Donald Trump’s successful, if once implausible US presidential campaign, Radev’s victory was yet another incremental geopolitical victory for Russian president Vladimir Putin, given Radev’s call for closer ties with Russia. Indeed, Tsacheva’s defeat was the proximate cause for Borissov’s resignation.

Instead, after the March 26 elections, GERB won 95 seats, the largest bloc in the National Assembly. Continue reading Bulgaria’s Borissov (and EU) gets reprieve from dissatisfied voters