It was first set of regional elections in the United Kingdom since Brexit. ![]()

![]()

But the impending conundrum of Brexit’s impact on Northern Ireland — the future of vital EU subsidy funds and the reintroduction of a land border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland that had become all but invisible within the European Union — wasn’t the only issue on the minds of Northern Irish voters when they went to the polls last Thursday.

The snap election followed a corruption scandal implicating first minister Arlene Foster — leader of the pro-Brexit Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) — that caused then-deputy first minister Martin McGuinness to resign from the power-sharing executive, forcing new elections, just 10 months after the prior 2016 elections.

* * * * *

RELATED: Why Northern Ireland is the most serious

obstacle to Article 50’s invocation

* * * * *

Politics in Northern Ireland runs along long-defined sectarian lines. Most of the region’s Protestant voters support either of the two main unionist parties — the socially conservative and pro-Brexit DUP or the more moderate Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), which backed the ‘Remain’ side in last June’s Brexit referendum. Most of the region’s Catholic voters support either of the two republican parties — the more leftist Sinn Féin or the more moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), both of which are fiercely anti-Brexit. An increasing minority of voters, however, support the non-sectarian, centrist and liberal Alliance Party.

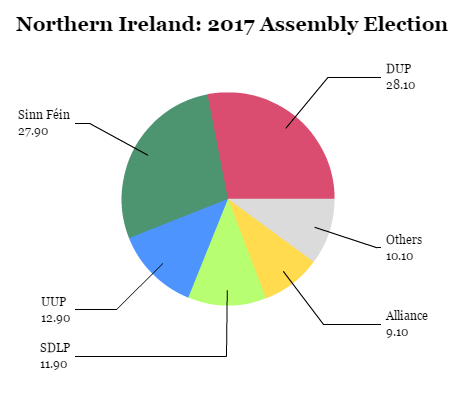

Since the late 1990s, when the Blair government introduced devolution and a regional parliament at Stormont, and when the DUP and Sinn Féin displaced the UUP and the SDLP, respectively, as the leading unionist and republican parties, the DUP has always won first place in regional elections. That nearly changed last Thursday, as Sinn Féin came within just 1,168 votes of overtaking the DUP as the most popular party.

It leaves the DUP with just one more seat than Sinn Féin and below the crucial number of 30 that it needs to veto policies. Without 30 seats, the DUP will no longer be able to block marriage equality (Northern Ireland lags as the only UK region that hasn’t permitted same-sex marriage) or an Irish language bill that would give Gaelic equal status with English in public institutions. It was high-handed for Foster — and Peter Robinson before her — to block the popular will on both of those issues over the last decade. That, in turn, is not helping the DUP in its bid to negotiate a new power-sharing deal with Sinn Féin.

More consequentially, it leaves unionists with a clear minority for the first time since devolution — just 40 seats in the 90-seat parliament (the number of deputies dropped from 108 members for the 2017 election). Most crucially of all, the election result creates a new equilibrium for the post-election talks between the DUP and Sinn Féin, which are now one week into a three-week deadline to form a new power-sharing executive, as guided by the British government’s secretary of state for Northern Ireland, James Brokenshire.

If the two parties do not reach agreement within the next two weeks, Northern Irish voters could head back to the polls for a second snap election in 2017 (and the third in a year). In a worst-case scenario, however, Brokenshire could reintroduce home rule from Westminster — a possibility that would disenfranchise Northern Irish voters as tensions run high over Brexit and its aftermath. With Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon threatening to call for a second post-Brexit referendum on Scottish independence and with the House of Lords forcing a final vote on any negotiated Brexit deal, a crisis in Northern Ireland is the last thing prime minister Theresa May needs.

So far, the negotiations aren’t exactly going well.

McGuinness, the militant-turned-peacemaker-turned-statesman, is not in the best of health, and he stepped down as his party’s leader when he resigned as deputy first minister. Michelle O’Neill, the new leader of Sinn Féin (in Northern Ireland; Gerry Adams remains leader in the Republic of Ireland) is taking a hard line, demanding at a minimum that Foster step down as first minister.

That’s not exactly outrageous, given that the DUP’s vote share dropped nearly 4% since the 2016 elections, and that the snap vote came about because of the ‘Cash for Ash’ scandal over a program — the Renewable Heat Incentive — that Foster herself put into place as the former minister of enterprise, trade and investment. The idea was to pay businesses to use renewable heating sources like wood pellets through subsidies. Eventually, recipients found ways to abuse the system to get ever larger subsidies to the tune of £490 million in spending. Some businesses and farms began heating otherwise empty buildings solely to receive the subsidy, which actually provided that for every £1 spent, recipients received fully £1.60 in subsidy.

It was as much boneheaded policy as it was fraud, and plenty of Foster’s DUP colleagues would be relieved to see Foster agree to step down.

But ‘Cash for Ash’ has deflected from the more serious debate over Brexit, which nearly 56% of Northern Irish voters rejected in last June’s referendum (lower than in Scotland, but obviously higher than in most of England and Wales). The Good Friday settlement that ended the ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland was finalized only 19 years ago, and it rests in large part on a seamless border between Ireland and Northern Ireland under the broad EU aegis that Brexit has now shattered. Any kind of border, however, might inflame tensions that had largely subsided.

There’s literally no good answer for May as she implements Article 50. A harder border could alienate both Catholic nationalist and inconvenience anyone who lives near the border. But May’s hard-right critics argue that no border — the status quo — leaves a wide-open back door to illegal migrants and trade from within the European Union (because the Republic of Ireland will remain an EU member-state). Border checks could once again become reality, though Brexit minister David Davis has tried to reassure Northern Irish citizens that a return to a ‘hard’ border with armed checkpoints is not under consideration.

In the post-Brexit world, Northern Irish republicans are now talking seriously about Irish unification for the first time in decades, and Adams openly points to Sinn Féin’s electoral success last week as an impetus to renewal calls for Irish reunification. Protestants (who skew toward unionism) make up around 43.5% of the Northern Irish population, and Catholics (who skew toward nationalism) comprise 40.5%. That’s a much narrower gap than in past decades, especially as atheism and agnosticism have grown. So a debate on Irish reunification will be based somewhat less on religious terms (as in the past) but on the policies, practicalities and benefits of unification — both for Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The 40-year-old O’Neill, a member of Stormont since 2007, was barely an adult when the Good Friday Agreement was signed. A generation removed from the armed conflict of the Irish Republican Army, she represents a new wave of Irish republicanism — like Sinn Féin’s deputy leader in the Republic of Ireland, 47-year-old Mary Lou McDonald — less weighted by the history of militant nationalism and defined by traditional social democratic views on social and economic policy.

The risk for O’Neill, Adams and Sinn Féin, however, is that they are overplaying their hands. Conceivably, there are many ways that London, Dublin and Belfast might ameliorate the adverse fallout from Article 50 (though not without some level of hassle for some group), and Northern Irish citizens are applying in record numbers for Irish passports.

There’s no doubt that, ‘Cash for Ash’ or not, Brexit was always going to catalyze a serious debate about Irish reunification and a potential border poll, both in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. But even with the DUP on the ropes, Sinn Féin still placed second overall. Moreover, the Sinn Féin surge came as a result of depressed unionist turnout. Unionists, perhaps jolted by republican success on March 2, might turn out in higher numbers in a second snap election. After the UUP failed to make significant gains and UUP leader Mike Nesbitt stepped down in the wake of the party’s disappointing result, the DUP might also consolidate what’s left of the UUP’s supporters, thereby emerging stronger than ever from fresh elections.

One possibility is that Sinn Féin has no intention of returning to a power-sharing deal, and so Brokenshire will have no choice but to introduce home rule. Perhaps that will chafe voters, thereby pushing undecided voters into the unification camp for an eventual referendum. But that seems far too attenuated a strategy for now, with plenty of space to backfire on O’Neill and Adams.

Needless to say, Belfast is quickly becoming a more painful headache for May, Brokenshire and the Conservative government in London.