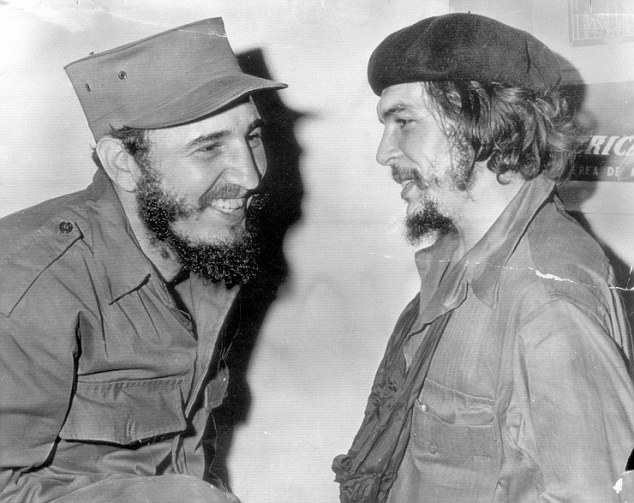

History will remember him in the same breath as Mandela or Gandhi for 1959.![]()

History will remember him in the same breath as all the other 20th century monsters for every year that followed.

That’s the tragedy and the shame of the Castro legacy.

Americans today bid farewell to a figure who played the role of foreign bogeyman for three generations, across the lengths of 11 American presidencies from Eisenhower to Obama. (Apparently, not even Fidel cared to stick around to watch the Trump administration, but could you imagine that showdown playing out at the United Nations or at the Organization of American States?).

In Cuba, and especially across Latin America, however, Castro more than anyone else in the 20th century delivered full independence to the region after years of sometimes malevolent and misguided American intervention. Before 1959, it was difficult to argue credibly that Cuba was truly independent. By showing that Latin America could go its own way, Castro became to many Latin Americans a modern-day libertador (even those that opposed his communist ideology — an ideology of necessity in the early 1960s for someone who wanted to thumb his nose at the United States).

Thirty years after Castro’s rise, and with the end of the Cold War, that’s an independence that even American policymakers begrudgingly admitted, bringing (mostly) an end to the days of CIA intervention and American shenanigans in Central and South American and the Caribbean. When US secretary of state John Kerry announced the end of the ‘Monroe Doctrine’ in 2013, the most striking thing was that no one really cared — to everyone else in the hemisphere, he was stating a blinding glimpse of the obvious.

That’s why so many prominent Latin Americans, from Gabriel García Márquez to beleaguered former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, with admirers in the United States, forgave in Castro so much.

Now that’s one hell of an ‘on the one hand…’

The Castro story with which most Americans are familiar is the one of the 1963 missile crisis, the Cold War brinksmanship, the tyrant that so animated the Cuban exiles in Miami, the Mariel boat lift, the camps for homosexuals and dissidents (long before his niece Mariela Castro decided Cuba should decree a full embrace of the LGBT community over the last decade). It’s not an incorrect story. But it’s important to acknowledge the role that Fidel Castro played in an entire region that stretches from Havana all the way to the icy tips of Argentina is far different from the role Castro played in the American imagination. It’s no exaggeration to say that soured US-Cuban relations had become the chief sticking point in American foreign policy in the 2000s and early 2010s.

Cubans themselves seemed weary and exhausted, at least from early reports out of Havana. For Cubans, Fidel has in every practical sense been gone for years.

It’s been a decade-long farewell, and as Raúl Castro, his brother, increasingly took power from an ailing Fidel, there were not-so-subtle signs from Fidel that he disliked his brother’s turn toward liberalizing the Cuban economy and restoring diplomatic relations with the United States. Both steps, long overdue and necessary for Cubans to have any chance at the kind of prosperity increasingly enjoyed throughout Latin America today, repudiated Fidel’s legacy. The hard Cuban left often spoke of Fidel in his final years as something like the leader of the opposition, in spirit if not actually in substance.

Though the world may now be done with Castro, Cuba has no such luxury, and the sighs of relief heard in Miami and elsewhere, coupled with hopes for a post-Castro opening to democracy and political freedoms, seem at odds with the reality today (however much you share the goal of a prosperous, democratic and free Cuba). Even a decade ago, Castro’s death might have caused a significant rupture; in 2016, the system that Castro built long ago outgrew the man himself, just as it seems likely to outlive his brother Raúl.

Fidel’s 85-year-old younger brother Raúl remains in power, and for all the talk of a peaceful handover in 2018 to a new president, Rául’s son Alejandro has increasingly strengthened his footprint in both the Cuban military and government. Don’t be surprised if, when all the smoke clears from the transition away from Cuba’s founding revolution generation, yet another Castro emerges, perhaps in the name of stability or continuity. The lurch in 2016, even among developed democracies like the United States and the United Kingdom, and among developing democracies like The Philippines, Hungary and Poland, toward illiberal populism, makes that possibly more likely.

Though the current favorite to succeed Raúl today might be first vice-president Miguel Díaz-Canel, the Cuban system is opaque enough to take that prediction with caution. But the names matter less than the reality for everyday Cubans.

There’s no guarantee (or, perhaps, even likelihood) that the transition to a market-oriented Cuba in a new diplomatic relationship with the United States, will become a place of any great political freedoms. Many Cubans that I spoke to in Havana in spring 2015 worried that the rapprochement with the Americans would leave their country stuck between the worst of both worlds — exposed to market capitalism without the previous decades of socialist protections for education, health care and welfare and stuck in the same authoritarian repression.