Everyone in Zambia always expected that its August 11 presidential election would be close.![]()

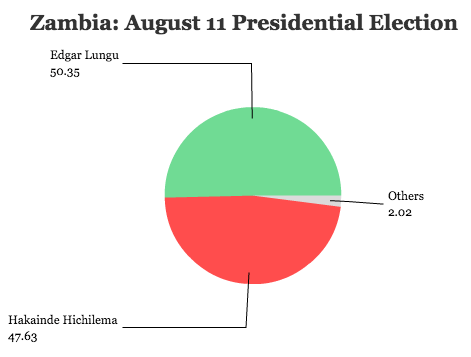

But the circumstances of Edgar Lungu’s narrow victory, officially pronounced on Monday by election officials, do not bode well. By a margin of around 13,000 votes, Lungu edged the 50% threshold required to avoid a runoff with his chief opponent, Hakainde Hichilema, a five-time presidential contender and the leader of the opposition.

The result leaves the country divided sharply on political, regional and ethnic lines and subject to weeks or even months of additional political uncertainty.

Hichilema has demanded a recount and is challenging the result in court. He has good reason, starting with the four-day lag between election day and the final tabulation of results. No results, as of Wednesday, were available for the constitutional referendum or the parliamentary elections that also took place August 11 to choose all 156 members of the National Assembly. A delay in counting votes from the capital, Lusaka, has cast additional suspicion on the possibility that the Lungu government might have won the election through fraud. Even the European Union’s observers have expressed their skepticism about the fairness of the voting.

It hasn’t helped help that Lungu leaned on state media significantly throughout the campaign, and that his government went out of its way to shut down The Post, one of the leading opposition newspapers in the country earlier this year. Nor did it help that Zambia, which has seen several peaceful transfers of power from one party to a different party, endured a greater amount of political violence than in past election years (though still quite mild by, say, Kenya 2007 standards).

* * * * *

RELATED: Hichilema hopes to win rematch in Zambia’s presidential race

* * * * *

Hichilema, meanwhile, expected to benefit from disenchantment with Zambia’s ailing economy and a depressed global market for its most important export, copper. His party, moreover, the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND), benefitted from the support of several high-profile defectors from Lungu’s Patriotic Front (PF). Results show that Hichilema did predictably well in the south of the country, Lungu won most of his votes in his northern base and, however narrowly, in the vote-rich capital, Lusaka, and in the Copperbelt province in central Zambia.

In fact, the results don’t look especially different from the results of last January’s presidential by-election, when Lungu (then Zambia’s defense minister) succeeded the late Michael Sata, though Lungu’s margin of victory (around 100,000 votes) is much wider in this year’s election than in the 2015 race (around 28,000). The 2016 election, moreover, featured much higher turnout — perhaps befitting the fact that Lungu, if his victory is confirmed, is now set to serve a full five-year term through 2021.

But the troubled economy, an increasingly polarized electorate and outrage from Hichilema’s supporters (especially in his stronghold, Southern province) about the conduct of the election have only amplified the notion that the vote tally may have been fraudulent. Earlier this week, the government arrested around 150 opposition protestors, fueling the divisions that have already been so fraught throughout the 2016 campaign.

Hichilema has valid concerns about the vote count.’s integrity While it’s plausible that Lungu genuinely (if not especially fairly) outpolled Hichilema, a successful businessman who was contesting his fifth consecutive presidential election, Zambians may never know if Lungu truly avoided a direct runoff without rigging the counting in Lusaka and elsewhere. Though support for third party candidate fell from around 5% in the 2015 race to just around 2% in the 2016 vote, a second-round vote between just Lungu and Hichilema might have gone a long way to assuage the opposition’s concerns, given that the country’s electoral laws were changed earlier this year to ensure than no president can be elected without a clear absolute majority.

Lungu would typically be inaugurated as soon as possible after the victory. To his credit, he is following a new law that stipulates a delay of his swearing-in until after Hichilema exhausts his judicial options. Lungu’s opponent has filed a court challenge to the election results, and the court will have up to two weeks to make a ruling on the UPND’s judicial challenge. If the vote is nullified, a new election must be held within 30 days.

Beyond the delays and the unfair nature of the competition, Hichilema hopes to point to specific examples of fraud:

Incidents ranged from the arrest of a suspected ruling party hacker caught in the verification room of the national totalling centre where official results were finalised, to mysteriously disappearing ballots, and claims that official forms with the final figures from polling stations and constituencies had not been given promptly to opposition party agents.

xx

i zambia we love upnd party and the reasons why upnd lost elections is hh we don’t want hh as a parpy president this why we voted for lungu,