Aleppo, the most populous city in Syria, has become in August the center stage for one of the most tragic urban battles of the country’s five-and-a-half year civil war.![]()

![]()

The first battle of Aleppo that began in July 2012 and lasted for months, brought some of the worst of the earliest fighting to an industrial and cultural capital home to some 2.5 million Syrians before the war.

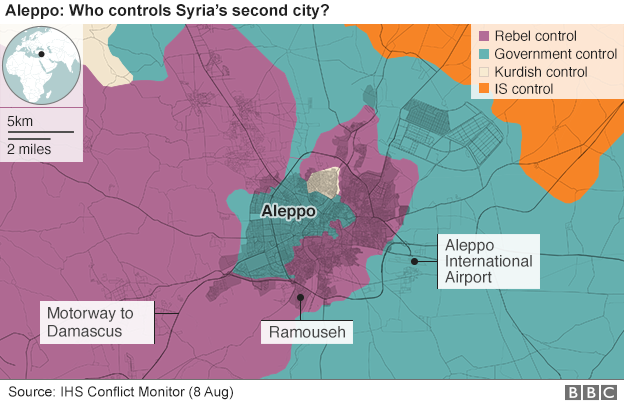

By early 2013, after thousands of deaths and widespread urban destruction (including parts of Aleppo’s old city and the Great Mosque of Aleppo), a stalemate developed between the eastern half, controlled by various Sunni rebel groups and the western half, controlled by the Syrian army that supports president Bashar al-Assad.

Last week, rebel forces — including the hardline militia formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra — broke through to Ramouseh, a key sector in the southwest of the city. Among other things, Ramouseh is home to some of the most important bases in the area for the Syrian army. More importantly, the rebel offensive hoped to open and secure a corridor between the besieged eastern half of Aleppo to other rebel-controlled areas to the south of Aleppo that could provide a pathway to food, water, power and other supplies to the rebel-controlled portions of Aleppo.

As of last week, the rebels had the upper hand after pushing into Ramouseh. Over the weekend, however, the Syrian army reclaimed some of its territory and effectively halted the rebel advance with punishing support from the Russian military.

Meanwhile, civilians across Aleppo (in both the government- and rebel-controlled areas) face a growing risk of a humanitarian crisis, lacking access to basic necessities like electric power, food and water in fierce summertime conditions. Intriguingly, Russia’s defense minister Sergei Shoigu also claimed over the weekend that Russian and U.S. forces were close to taking ‘joint action’ on Aleppo. It’s odd because Russian president Vladimir Putin firmly backs Assad, while US officials have expressed the view that Assad’s departure alone can bring about a lasting end to the civil war. One possibility is a pause in hostilities to allow aid workers to provide food, water and medical care to civilians caught in what has become one of the deadliest battles in the Syrian civil war to date.

As the battle for Aleppo dominates headlines about Syria’s war, it is quickly becoming a symbolic fight for Syria’s future.

A rebel victory in Aleppo would mean a grievous setback for Assad and the Syrian army, but also for the Russian army, the Lebanese Shiite militia, Hezbollah, and other Assad allies, like Iran. A government victory in Aleppo would give Assad a significant boost, because Aleppo has been the largest urban holdout for rebel forces.

Continued stalemate would subject Aleppo’s civilian population (especially on the eastern rebel-controlled side) to continued threat of a humanitarian crisis.

If you want a quick peace, you might hope that a renewed Assad/Russian counterattack can break rebel control of Aleppo for good, facilitating the end of the war (albeit on terms favorable to Assad, Russia and Iran). An emboldened rebel victory could prolong the war for months or years, and a rebel victory might easily end in a de facto or de jure divided Syria, with spillover effects in Turkey, Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan, and with new Syrian leaders potentially far more barbarous than Assad, including those who would like to engage in jihad against Europe and the United States.

So as U.S. officials continue to talk with Russian officials over a solution and, hopefully, meaningful peace talks, what role should the United States play in Aleppo? It’s hard to imagine that any joint Russian-American operation could do much more than to create a space for humanitarian relief and, even then, it’s hard to imagine that the two countries have developed enough trust to coordinate even that effort.

The Obama administration, though it backed down from launching air strikes in August 2013 at the Assad government, notably worked with Russia for a diplomatic solution to remove a chemical weapons arsenal out of Syria. Though Obama has received massive criticism domestically for backing away from his own ‘red line’ on intervention, the outcome was, on balance, successful. It was an opportunity to further diplomacy with Russia, and it resulted in the peaceful evacuation of the most lethal chemical weapons in Syria. Nevertheless, there are reports of chlorine gas attacks in Aleppo in recent weeks and, while chlorine isn’t as potent as chemical agents like sarin, its use is increasing disconcerting.

Since 2011, the Obama administration’s view has been that Assad must go. So any intervention in favor of the Syrian military would ally the United States with one of the most brutal dictators in the world today, who launched his country into civil war and opened Syria’s territory to takeover by hardline extremists like ISIS because he refused to countenance moderate protests that were taking place across the region in the 2011 ‘Arab Spring’ movement. Assad (or at least officials close to Assad in the Syrian military) have clearly shown their willingness to attack civilians, including with sarin and other chemical weapons, in their quest to take control of Syria in the last five-and-a-half years.

All along, many American voices have argued that the Obama administration should arm and train the more moderate of Syria’s rebel forces, including former US secretary of state Hillary Clinton, now the Democratic Party’s nominee to succeed Obama as president. Among the anti-Assad forces, the initially strongest in 2011 and 2012 were the Free Syrian Army, a group of military officials who defected from Assad’s military, disgusted at the way he was willing to put down peaceful protests.

By 2013, however, other more militant groups came to dominate the anti-Assad efforts, some aligned with al-Qaeda and some with ISIS, which declared a caliphate in eastern Syria and western Iraq, and which governs its territory with barbarous cruelty — though Kurdish militias, the peshmerga, with US air support are having some success in beating back ISIS.

Groups like ISIS and the Qaeda-linked Jabhat al-Nusra were willing to use more extreme tactics, like suicide bombings, to win decisive victories against the Syrian military. With those successes came increasing dominance among the Sunni rebels, generally. Those who criticized U.S. intervention argue that arming the Free Syrian Army in 2011 and 2012 only would have resulted in American arms in the hands of extremist Sunni groups, including ISIS. (Supporters argue that early, firm intervention by the Obama administration might have prevented the emergence of extreme groups, though that’s not necessarily clear). Sunni rebel groups have killed Christians across Syria, engaged in beheadings of their enemies and destroyed long-standing sites of cultural heritage.

Most recently, Jabhat al-Nusra has taken the lead in the fight for Aleppo, in part by using extreme tactics like suicide bombing. In July, it changed its name to Jabhat Fateh al-Sham and denounced its ties to al-Qaeda. By denouncing links to al-Qaeda, the group might more easily integrate with other anti-Assad groups and, in theory, that should make US support more palatable. But Jabhat Fateh al-Sham remains an extremist rebel group and its growing dominance in Aleppo limits any kind of US intervention on behalf of the anti-Assad forces.

An Assad victory? A victory for Jabhat Fateh al-Sham? Prolonged stalemate, widening refugee crises and growing enclaves of jihadist Sunni rule? None of these, from any perspective, are good results for the United States.

So as Aleppo’s siege becomes a widespread humanitarian crisis and there’s a crescendo of calls for the Obama administration to ‘do something,’ it’s important to realize that there really are no good options.

Syria’s civil war, despite Russian, Iranian, Turkish, Saudi, Kurdish, Qatari and Lebanese intervention, is still for Syrians to fight.

It’s a sobering thought that even a mighty superpower like the United States cannot solve it (even though American operations in Iraq helped to inflame the sectarian passions now fueling the Syrian war). The best that the Obama administration, or Obama’s successor, can do is to assist as possible to facilitate humanitarian aid, smooth the path for Syrian refugees abroad (including in Lebanon) and keep diplomatic lines open for a peace deal that, ultimately, may keep Assad in power or split Syria into one or more smaller states.

There’s no magic bullet. Americans cannot guarantee, with any intervention, the kind of stable and prosperous Syria that so many of its citizens yearn for. Indeed, as in Iraq and Libya, American or NATO intervention might make matters worse. That’s not a satisfying conclusion. But it is, at least, honest.

I hope the Syrian government wins. Whatever the insurrection was in 2011, it is now taken over by Salafist terrorists. Al Qaeda, by whatever name, is in charge. Rebels we have backed have either joined in al Qaeda’s battles or have fled the field turning over their weapons to terrorists. President Bush declared war on international terrorists. We have given up our liberties to fight this war. We have spent billions of dollars on this war. Thousands of Americans have died in this war. Tens of thousands of American soldiers have returned with physical and mental injuries. To ally ourselves with the very people we have sacrificed so much for would be an insult to all America and especially for those who lost a loved one. Everyone criticized Trump for his comments about the Khan family, those who now advocate to supply more weapons or provide air cover for these terrorists are no better.