In a region rife with lopsided one-party democracies dominated by independence-era freedom movements (South Africa, Mozambique, and Namibia) and clear autocracies (Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zimbabwe), one country stands out for free and fair elections that aren’t also forgone conclusions.![]()

It’s Zambia, a country of 16.2 million people, which will hold its fifth presidential election in ten years on August 11, a rematch of last year’s election that takes place as the Zambian economy, the continent’s second-largest producer of copper, enters a troubled period as global commodity prices remain depressed. That’s meant fewer revenues for the Zambian government over the last two years, a wide increase in public debt and a gaping hole that’s led to power outages, deep rises in the price of food and other economic difficulties.

The winner of the Thursday election will almost certainly be forced to seek a bailout package from the International Monetary Fund this autumn, along with the kinds of conditional austerity that will cause real economic pain in the years ahead.

A re-run of the January 2015 by-election — with higher stakes

The 2016 election amounts to a rematch from the January 2015 by-election to replace the late Michael Sata, who died unexpectedly in October 2014. Sata’s governing party, the Patriotic Front (PF), ultimately chose Edgar Lungu (who is now just 59 years old), who had previously served as Sata’s justice minister and defence minister. Briefly, Sata’s vice president, Guy Scott, a white Zambian, held the title of acting president and, for a short time, considered running against Lungu for the presidency.

Instead, Lungu’s chief competitor became four-time presidential contender Hakainde Hichilema, a businessman and the candidate of the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND).

Lungu narrowly won — by a margin of less than 28,000 votes, on a populist campaign that rested largely on the record that Sata accumulated before he died. Hichilema campaign largely on a campaign that promised greater fiscal and technocratic competence in a period when copper prices were already falling. They are, to a large degree, running on the same rationales in 2016.

Lungu and the PF dominated in the north, center and east of the country, including the densely populated urban areas in the capital city of Lusaka and, to a lesser degree, Copperbelt province. Hichilema easily won the south, the west and the northwest.

This time around, the two candidates are locked into a rematch, but with much larger stakes — the 2016 winner will govern Zambia for five years, not just 18 months. That, perhaps, explains why the campaign has veered into a troubling amount of political violence this summer. The violence, which forced Zambia’s electoral commission to ban campaigning in Lusaka for 10 days in mid-July, has caused some hand-wringing among both local and foreign observers, who worry that the violence is a sign that the campaign could erode democracy in Zambia. It’s true that the Lungu government shut down the country’s largest independent media organization, the Post, earlier in the spring, eroding the concept of press freedom across the country.

Zambia’s democratic bona fides remain strong

Headlines in Western news outlets about Zambian democracy ‘hovering on the precipice,’ however, are certainly overblown. Democracy is more deeply institutionalized in Zambia than in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa, and it features one of a handful of just a few truly competitive political systems in southern and central Africa.

Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s first post-independence president, conceded defeat to Frederick Chiluba of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) after Kaunda’s lopsided defeat in the 1991 election, which followed a 27-year grip on power.

That landmark 1991 vote established a pattern of consistent elections every five years. Two decades later, the MMD’s sitting president, Rupiah Banda, peacefully transferred power after narrowly losing the 2011 election to Sata and the Patriotic Front.

Of course, the two-decade period of MMD rule wasn’t a model of perfect democracy. The Chiluba and Mwanawasa eras were imperfect, marked with corruption and abusive curbs on freedoms. But instead of sliding into an autocracy, enough MMD officials defected to Sata’s movement. In 2016, there’s some sense that many one-time Sata partisans are doing the same to the Lungu government, as several key politicians have abandoned the PF for Hichilema.

If Hichilema wins on Thursday, and if Lungu peacefully transfers power, it will mark three such benign handovers from one party to another. It’s an imperfect comparison, but it took the United States of America nearly a half-century to mark three such transfers of power, when Martin Van Buren (a Democrat) ceded victory in 1840 to William Henry Harrison (a Whig).*

Voters will also choose 150 members of the National Assembly through first-past-the-post districts across Zambia, with the president to appoint eight additional members and a speaker elected from outside the parliament. Even more notably, they will also vote on introducing a new Bill of Rights to the new Zambian constitution, which will supplement the current civil and political rights and add new economic, social, cultural and environmental rights. (Here’s a comic book from the Zambian government that describes the referendum in greater detail).

The new Bill of Rights, if approved, will make it even more difficult for future Zambian administrations to roll back democratic norms that have only deepened for the last three decades.

New year, new election, new rules

This year’s presidential contest, however, takes place under a slightly revised electoral system, following constitutional reforms that the Lungu government finalized earlier in 2016. If no candidate wins over 50% of the vote, the top two finishers will compete in a direct runoff. Notably, no Zambian candidate has won the presidency with over 50% of the vote since 1991 and 1996 (when Chiluba won over 70% of the vote), and in some cases, like in 2001, Levy Mwanawasa won the presidency with less than 29% of the vote in a multi-party candidate field.

For example, in the 2015 by-election, even though he won more than 48% of the vote, Lungu would have been forced into a runoff against Hichilema, which (theoretically) might have boosted Hichilema to the presidency. In the 2016 race, again, only Lungu and Hichilema have a serious shot at the presidency, but it’s important to note that seven other contenders could win enough marginal support to deny one of the two major candidates a clean absolute majority, making it more likely than not that Lungu and Hichilema will face off again. (The seven also-rans include Tilyenji Kaunda, the son of Zambia’s former president, who in his prior 2015 bid won all of 0.58% of the vote).

The new rules also require each presidential candidate to choose a running mate who can serve upon the death or incapacitation of the elected president. That makes sense, given that the last two elected presidents have died in office, each case necessitating a by-election. Levy Mwanawasa, the MMD candidate elected in 2001 and reelected in 2006, died in August 2008, forcing a by-election in October 2008, in which Rupiah Banda very narrowly defeated Michael Sata. When Sata won his own mandate in the regularly scheduled 2011 election, of course, his death in October 2014 forced yet another by-election.

While Lungu is sticking with his vice president, the 77-year-old Inonge Wina, previously the minister for gender and child development under Sata.

But Hichilema shrewdly reached out to a former PF minister as his running mate, Geoffrey Bwalya Mwamba, a former PF member from northern Zambia (traditionally the PF stronghold), who served as Lungu’s predecessor in the defence ministry.

There’s an ethnic element to the vice-presidential calculus as well.

Sata and Mwamba — unlike Lungu — was a member of Zambia’s largest ethnic group, the northern-based Bemba, so many voters in northern Zambia might be far less enthusiastic about supporting Lungu.

Hichilema, a member of the southern Tonga ethnic group, has a track record (over four prior elections) of delivering high voter turnout in the south, and that could push him to victory if turnout in the north and in urban areas is low, especially if Hichilema manages to attract the suppot of a few former Sata voters.

Economic decline is scrambling old coalitions in 2016

Mwamba is just one of several members of Sata’s inner circle to defy Lungu and leave the PF. Guy Scott (the short-lived acting president, who was for a short period the only white president in continental Africa) has also now endorsed Hichilema, as have several members of the Sata family, including the late former president’s son, Mulenga Sata.

Rupiah Banda, however, the man who briefly served as president between 2008 and 2011, has endorsed Lungu. But the 79-year-old Banda has not campaigned nearly as hard for Lungu this year as in 2015. The MMD, the party that dominated Zambian government between 1991 and 2011, isn’t even fielding a candidate in 2016, so many of its lingering supporters are up for grabs. Nevers Mumba, the nominal leader of the MMD, now a divided remnant of its former juggernaut, has endorsed Hichilema, however. So is Maureen Mwanawasa, the widow of the former president, who is also, incidentally, running for mayor of Lusaka.

Hichilema, for the better part of a decade, has retained strong support in his stronghold, Southern province; Sata and the PF have dominated the urban Copperbelt and Lusaka provinces. But the MMD triumphed in 2006 and 2008 by sweeping up votes everywhere else — in the Northern, Central, Eastern, North West and Western provinces. Those dwindling MMD supporters, therefore, might be crucial in the current race. If Mumba and the Sata loyalists can deliver just a few of their supporters in the northern and eastern half of the country, Hichilema will be the favorite to win on Thursday.

Is it all China’s fault?

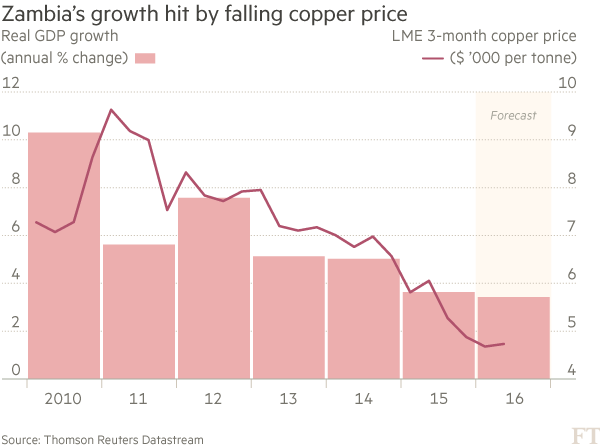

The rationale of the Hichilema juggernaut, Banda aside, seems simple enough by political logic. As the price of copper has collapsed, so has GDP growth — from over 10% six years ago to around 4% today.

Sata rode to power on a populist campaign five years ago that responded to growing unease with the outsized Chinese influence in Zambia (especially in the copper mining industry). In office, he raised royalties on open-pit copper mines from 6% to 20%, which gave Sata the funds to develop Zambian infrastructure and effect a public sector pay increase. When the price of copper collapsed, however, the Zambian deficit ballooned (from a nominal amount when Sata took power in 2011 to the unsustainable rate of nearly 7% of GDP today). Like many emerging economies, the value of Zambia’s currency, the kwacha, has collapsed — losing nearly 80% of its value against the US dollar in 2015 alone (though it has rcovered some of its value in 2016). Lungu, having won the January 2015 by-election, was stuck figuring out how to pay Sata’s bills.

That’s made Lungu, predictably, an unpopular figure presiding over a difficult economy. Though he has campaigned on the infrastructure gains that Sata put into place (and those projects are indeed substantial), voters are naturally asking: ‘What have you done for me lately?’

The problem with China in 2016 is that its own economic slowdown has depressed the market for Zambian copper, nearly obliterating the country’s exports.

If Alberta’s premier Jim Prentice was the first official to lose an election over the current collapse in global oil prices, Lungu could be the first president to lose power as a direct result of China’s economic slump. A Lungu defeat could be a harbinger of political change (in democracies and otherwise) across Africa and Asia in the years ahead if China’s GDP growth doesn’t bounce back.

Given economic conditions, Lungu has few good answers to that question. Historically, no matter where you are in the world, that’s never a great position from which to wage a reelection campaign.

* The first transfer of party-to-party power took place in 1800, when Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic Republicans defeated John Adams and the Federalist Party; the second was in 1828, when Andrew Jackson’s populist Democrats defeated John Quincy Adams and the Democratic-Republicans.