When pro-Leave campaigners argued that, by leaving the European Union, Great Britain could ‘take back control,’ one of the clear things over which Brexit proponents seem to want to take control was national borders.![]()

![]()

Given that Great Britain itself is an island, that’s mostly a theoretical proposition, because you can’t step across the border into England, Scotland and Wales — their ‘borders’ are through their seaports and airports.

That’s not true in Northern Ireland, the only region in the United Kingdom that does share a land border with another European Union member-state. It’s also one of the most delicate tripwires for British prime minister Theresa May in her dutiful quest to invoke Article 50 of the European Union’s Lisbon Treaty next year and begin negotiations for a British EU withdrawal.

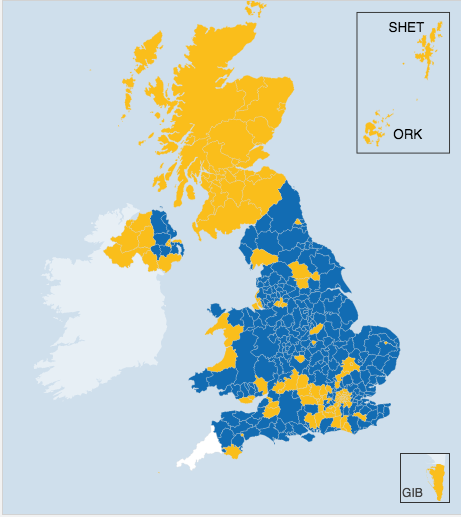

Scotland has garnered more headlines because Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon has argued that Scots, who voted strongly for Remain, deserve a second independence referendum when the British government finally does leave the European Union. But if ‘Remain’ proponents are looking to the one part of the United Kingdom that could impossibly prevent Article 50’s invocation, they should look to Northern Ireland, where Brexit could unravel two decades of peace, and where Brexit is already causing some anxiety about the region’s future.

May, just days after replacing David Cameron at 10 Downing Street, visited Belfast earlier this week in a bid to reassure both unionists and republicans. But it’s not clear that May’s first journey to Northern Ireland, which preceded a meeting with Ireland’s leader a day later, was a success.

May boldly claimed that Brexit need not result in the return of a ‘hard border’ between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. But settling Northern Ireland’s Brexit border issue is virtually intractable for the May government — at least without alienating one of three crucial groups of people: first, the mostly Catholic republicans of Northern Ireland; second, the most Protestant unionists of Northern Ireland or finally, those Brexit supports across the entire country who voted ‘Leave’ in large part to close UK borders to further immigration.

As in Scotland, Northern Ireland’s voters narrowly titled against Brexit — 55.78% supported ‘Remain,’ while just 44.22% supported ‘Leave.’ Generally speaking, republicans widely supported ‘Remain,’ and unionists leaned toward ‘Leave,’ including first minister Arlene Foster.

Under the terms of the 1998 Belfast Agreement — more popularly known as the Good Friday Agreement — the border has been open for nearly two decades, without so much as a customs agent waiting to stop motorists on a line between Irish territory and British territory that has largely disappeared. Today, more than 30,000 people cross daily what amounts to an invisible border between the two countries. The Good Friday agreement, moreover, rests precisely on the premise that the border has become increasingly invisible, and that agreement built upon the foundations of the Common Travel Area established in the 1920s.

Fitting three groups of people into a two-dimensional Brexit

For Northern Ireland’s republicans, that’s enough to make the entire island of Ireland ‘feel’ like a united country, and it’s largely settled the once-raging issue of Irish reunification. Until June 23, the idea of holding a referendum on a united Ireland seemed extremist and outlandish. But if May re-introduces the Irish border, however ‘soft’ she wants to make it, the move will almost certainly stoke Irish nationalist sentiment.

For Northern Ireland’s unionists, the open border is one element of a deal that has brought increasing peace and prosperity to Northern Ireland after the 30-year Troubles, which caused sporadic fighting between the two groups and that often forced British forces to intervene with bloody and sometimes lethal results.

It should come as no surprise that borders, once erased, are difficult to reintroduce.

Yet without at least some border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, workers from the rest of the European Union (or, potentially, smugglers hoping to evade future British or EU tariffs) could easily enter British territory by flying first to Ireland, driving to Belfast, the Northern Irish capital, and flying onward to Britain. For all the talk of taking back the United Kingdom’s borders, it would be impossible to do so without at least some land border, ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ as it may be.

One alternative might involve a special check for all passengers arriving in Scotland, England or Wales from Northern Ireland. But that would be an insult to all Northern Irish citizens, who would be subject to internal checks in their own country. It would, in particular, rankle unionists who supported Brexit, to find that it would mean a curb, however slight, to their own freedom of movement. May seems to have already ruled out this option.

On Monday, May met with Foster, Northern Ireland’s first minister and a member of the center-right and mostly Protestant Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and with deputy first minister Martin McGuinness, a member of the Irish republican Sinn Féin, hoping to reassure both officials and their two disparate constituencies:

“What we do want to do is to find a way through this that is going to work and deliver a practical solution for everybody – as part of the work that we are doing to ensure that we make a success of the United Kingdom leaving the European Union – and that we come out of this with a deal which is in the best interests of the whole of the United Kingdom,” she said.

Foster, who supported Brexit, only became first minister in January, when she succeeded Peter Robinson, a social conservative who had served nearly eight years as first minister. Under the unique power-sharing system, the two parties govern together at Stormont, the Northern Irish parliament, with 67 of the Northern Irish assembly’s 108 seats, despite holding very disparate views of policymaking. It’s an arrangement, settled by the Good Friday Agreement, that has largely kept the peace in Northern Ireland.

What does a ‘soft’ border between Ireland and Northern Ireland mean?

May welcomed Enda Kenny, the Irish taoiseach (prime minister) to 10 Downing Street on Tuesday, the first EU leader to visit the new prime minister. Both maintained that Brexit could work without a ‘hard’ border.

It all begs the question — what, in May’s view, would a ‘soft’ border look like? Customs checks for goods coming into Northern Ireland? Full passport checks? Would it be feasible or cost-effective to play border agents, however innocuous, on every country lane along a 499-kilometer border? A ‘soft’ border, without the barbed wire or gun-toting soldiers of the past, would nevertheless prove an inefficient hassle for those who cross today’s near-invisible border. Even a ‘soft’ border could reinforce divisions in Ireland, which could agitate republicans in both countries for a referendum on reunification — or even a return to violence.

To make matters worse, the financial impact of Brexit on Northern Ireland could be far more severe than in the rest of the United Kingdom, both because the open border has facilitate trade between Northern Ireland and Ireland and because Northern Ireland receives significant regional funding from the European Union as a result of the Good Friday agreement — up to £2 billion alone between now and the year 2020. That’s on top of nearly £9 billion that London currently pumps annually into Northern Ireland’s state-heavy economy already.

Since becoming prime minister, May has reiterated that she wants to make Brexit work for all parts of the United Kingdom, above all for Scotland and Northern Ireland. But at some point, she’ll have to make hard choices about economic, border and other trade-offs, and the Northern Irish issue will be just one of dozens of difficult issues. She’ll have no particular amount of goodwill across the region, even from her natural allies in the unionist camp. Her new secretary of state for Northern Ireland, James Brokenshire, has been a Conservative MP from greater London since 2005, grew up in Essex in the south of England and has no real experience on any issues of particular significance to Northern Ireland.

Will Article 50 lead to mayhem… or Irish unification?

Nevertheless, how many violent incidents in Northern Ireland could May tolerate before delaying (or scrapping altogether) her invocation of Article 50? A return of sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland wouldn’t just spook Belfast. It could spook Dublin, and it would unsettle global markets about security in London. It will be tough enough for May and the new ‘Brexit’ secretary David Davis to secure for London’s financial services industry access to the European single market. But the possibility that a new Northern Irish conflict could erupt would weigh heavily on London as it seeks to secure a continuing role as a global financial capital in a post-Brexit world.

Irish republicans clearly certainly know that the looming threat of a new land border gives them leverage. McGuinness himself, just hours after the Brexit vote, recognized that leverage. He almost immediately demanded a referendum on Irish reunification, arguing that the British government had ‘forfeited any mandate to represent the economic or political interests’ of the Northern Irish people. Indeed, the Good Friday Agreement permits the British government to allow a border poll on Irish unification, if it reflects popular sentiment.

But the DUP and their unionist supporters would not likely support unification. The two largest unionist parties (the DUP and the Ulster Unionist Party) together won 41.8% of the vote in the May 2016 regional elections, while Sinn Féin and the nominally republican Social Democratic and Labour Party together won 36%. It would be an ugly and divisive fight.

May will have her hands full enough preventing the calls for a fresh Scottish vote on independence and navigating the British government through the Article 50 negotiations. The border poll calls leave her in a lose-lose scenario. If she refuses a referendum in Northern Ireland, she risks inflames republican sentiment even further. If May, however, consents to a border poll, she risks highlighting the real cracks in public sentiment between republicans and unionists. All of this, by the way, could come at a time when the entire country is enduring a Brexit-triggered recession and Northern Ireland, in particular, fears bearing the brunt of a Brexit-induced economic gap that will take years or possibly decades to fill.

In the days after Brexit, a rush of Northern Irish citizens rushed to complete forms to apply for an Irish passport. Anyone born (or whose parents were born) on the island of Ireland can automatically qualify for a passport, and the grandchildren of Irish-born grandparents can apply for a passport. So one answer, of course, might be to give everyone in Northern Ireland an Irish passport, making everyone on the island of Ireland, in essence, an Irish citizen — and an EU citizen, will all the rights than their British brethren will no longer receive.

It would, incidentally, add 1.8 million Northern Irish citizens, many of whom are highly trained, highly educated and English-speaking workers, to an Irish workforce. That’s significant for a country with just 4.6 million people today.

In the long run, however, that could hollow out Northern Ireland demographically, economically and politically, and you’d hear a ‘giant sucking sound’ from Belfast to Dublin. Within a generation, unification’s supporters would grow, out of sheer efficiency and to give Northern Ireland a fighting chance at real economic development. (Full EU rights for the Northern Irish would also turn the more fervently pro-European Scotland, and its ever-widening base of nationalists, green with envy).

Kenny and Irish foreign minister Charlie Flanagan have for the first time broached the topic of Irish unification. Kenny himself compared it to the reunification of West and East Germany, though the partition of Ireland has endured since 1922, far longer than Germany’s 41-year division. At least one economic study last year showed that unification could land Ireland a windfall of up to €35.6 billion in output in its first eight years, much of it going to Northern Ireland. That’s a mighty incentive.

Nevertheless, a border is still a border. And if tensions do rise, May might one day be forced to make the hardest choice of all, between respecting the democratic will of a country that (narrowly) voted to leave the European Union, on the one hand, or risk plunging Northern Ireland back into the violence that ended with the Good Friday Agreement, on the other hand.

“James Brokenshire” Ironic name! Just hope it doesn’t become “Brokenstate”! Since this does appear to be a critical issue I can’t understand why he was selected to head this post?

Re: “Yet without at least some border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, workers from the rest of the European Union (or, potentially, smugglers hoping to evade future British or EU tariffs) could easily enter British territory by flying first to Ireland, driving to Belfast, the Northern Irish capital, and flying onward to Britain.”

Not necessarily. Even to board a domestic flight (for example, here inside the United States), a traveler needs to present an identity document. Without even a “soft” boarder between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland, the UK could still police third-country transiting by permitting holders of UK and Irish passports to travel to the Big Island without further ado, while referring holders of all other passports to UK entry checks.