It’s not every day that hopes for reform and good government lie more with reelecting the dominant party that’s held power since 1977 than with opting for the opposition.![]()

But increasingly, that seems to be the case in Tanzania, where the October 25 general election pits John Magufuli, the standard-bearer of the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM, Party of the Revolution) against Edward Lowassa, one of the CCM’s former presidential hopefuls and a disgraced former prime minister. Lowassa is running as the candidate of the Ukawa opposition front that includes Chama Cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (popularly known simply as Chadema), a liberal opposition party formed in 1992, and Chama Cha Wananchi (CUF, Civic United Front), the Zanzibar-based opposition party.

Changing places?

Though Lowassa is the wilier politician, the CCM is still favored to hold onto power after Sunday’s elections. Since multi-party politics were introduced in 1992, the CCM has had little trouble maintaining its lock on the Tanzanian government. On the mainland, at least, the CCM (and before 1977, its predecessor, the Tanganyika African National Union) has been virtually interchangeable with government.

But Lowassa’s popularity as a former CCM official, the desire for change among the country’s powerful youth, and growing opposition strength in Zanzibar have made this year’s elections particularly unpredictable.

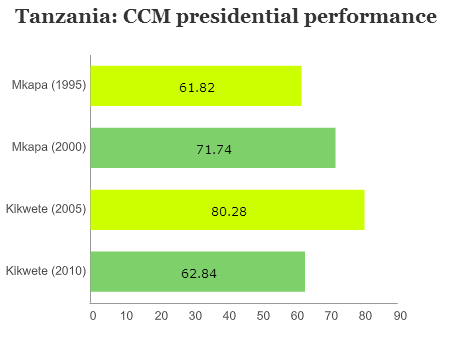

The current contest between Lowassa and Magufuli has its roots in the tussle earlier this year to determine the CCM’s successor. Jakaya Kikwete, Tanzania’s fourth post-independence president, is term-limited and, while he’ll continue to lead the CCM until 2018, he will leave the presidency after a decade in office, generally maintaining Tanzania’s stable path to greater development.

Lowassa, a longtime figure within past CCM governments, served as Kikwete’s first prime minister from 2005 until 2008, when he resigned over a bribery scandal involving a fraudulent contract between a Houston-based energy company and Tanzania’s publicly owned power generation company. When Lowassa launched his presidential bid in May, however, Kikwete and the CCM’s national executive committee excluded Lowassa from a shortlist of five final candidates — a shortlist that included Magufuli, former UN deputy secretary-general Asha-Rose Migiro and Kikwete’s apparent favorite, foreign minister Bernard Membe.

Unable to compete, Lowassa and his allies worked to deny the CCM nomination to Membe, paving the way for Magufuli, Tanzania’s minister of works since 2010 and a previous minister of lands and human settlements and a minister of livestock development and fisheries. Needless to say, he is something of a dark-horse to lead the CCM into the 2020s:

Magufuli has a reputation for being serious, honest and hardworking, and also for being one of the government’s best ministers, but he is not regarded as a party insider or heavyweight. Magufuli’s elevation to be the CCM’s candidate was a political accident – an accident that could hurt the CCM’s chances of retaining its large majority in parliament or retaining the presidency.

With the CCM path to the presidency closed to him, Lowassa promptly decamped to Chadema, which welcomed him with open arms as its presidential nominee in August. The decision, however smart politically, came at odds with the party’s anti-corruption platform. Chadema‘s 2010 candidate, Wilbrod Slaa, endorsed Magufuli in light of Lowassa’s well-known and widely discussed record of corruption. Unlike most opposition movements in sub-Saharan Africa, Chadema in 2015 is hardly mounting a traditional anti-corruption campaign against an entrenched ruling elite because Lowassa, much more than Magufuli, represents the corrupt elite. Nevertheless, Lowassa has genuine support in northern Tanzania, and he has brought traditional CCM supporters to the Chadema effort with a flashy campaign during which Lowassa has criss-crossed the country by helicopter. It will certainly be the closest presidential contest in Tanzanian history.

The CCM’s superior organization and Lowassa’s reputation for corruption means that the ruling party is probably still favored to win, but the campaign has been a rigorous showcase for democracy.

It’s happened before. In 1995, home affairs minister and former deputy prime minister Augustino Mrema defected from the ruling CCM in what would become the first multi-candidate presidential election in Tanzanian history. In that race, the soft-spoken, technocratic minister for science, technology and higher education, Benjamin Mkapa easily held off the more powerful Mrema.

But 20 years ago, the TANU/CCM was much more powerful, linked to the memory of Tanzanian independence, and Nyerere himself was still actively mobilized supporters. Today, the median age in Tanzania is 17.4, making it the 11th youngest country in the world. Nyerere, it’s worth noting, died in October 1999, just over 16 years ago. Barring any post-election violence or credible accusations of vote-rigging, a close race could make Tanzanian politics much more competitive in the future.

Zanzibar’s election even tighter

That future seems to have already arrived in Zanzibar. Despite the headlines about the Magufuli-Lowassa contest, it’s the Zanzibari presidential election that you should watch with even more interest.

Given a remarkable amount of autonomy in 1964, Zanzibar elects its own president and parliament, and those elections also take place on Sunday. Given the CCM’s political hegemony, however, Zanzibar’s autonomy has never really been tested by adverse governments. Culturally, Zanzibar is more like Kenya’s Somali coast or Mombasa than the rest of Tanzania. Unlike the mainland, where both Christianity and Islam are both predominant, Zanzibar (home to just 1.03 million people) is almost entirely Muslim.

The CUF only narrowly lost the 2010 presidential election, with the CCM’s Ali Mohamed Shein taking a slim victory of 50.1% to 49.1%, a vote that the opposition blamed on fraud. This year, the incumbent once again faces his 2010 opponent, the CUF’s Seif Sharif Hamad. Post-election violence flared after the 2000 vote, and if the CUF is once again denied the Zanzibari presidency, it could be even worse in 2015. Though the CCM’s grandees argue that a CUF victory could destroy the Tanzanian union, Zanzibar’s elections could show that the country’s federal structure can withstand a peaceful transfer of power.

From ‘ujamaa’ to regional standard-bearer

As far as African post-independence stories go, Tanzania’s is essentially one of modest success. The country is a federation of Tanganyika, the mainland that lies to the south of Uganda and Kenya, and the neighboring Indian Ocean islands of Zanzibar, a former sultanate unified as part of Tanzania in 1964, after a short-lived, left-wing violent revolution on the islands that overthrew Zanzibar’s sultan.

Julius Nyerere, Tanzania’s first post-independence presidency was a respected visionary whose socialist ideals failed to develop the country economically.

Its first leader, Julius Nyerere, was an honest visionary whose socialist ideas for Tanzania were higher on promise than actual performance. Under the banner of his ujamaa (‘familyhood’) doctrine, rural villages were collectivized, sometimes by force, to disastrous results. The country’s poor didn’t starve thanks to an influx of foreign aid. The Nyerere era, however, boosted the country’s education and health care systems and it solidified a Tanzanian national identity over ethnic, religious or other identities, unlike in neighboring Kenya. Today, Tanzania is a relatively united country of nearly 52 million people, making it the most populous country in east Africa and a crucial hub between the east African and southern African markets.

Nyerere stepped down in 1985, and his successor, Ali Hassan Mwinyi (a Zanzibari) quickly introduced market reform and a structural program guided by the International Monetary Fund. Since the late 1980s and 1990s, Tanzania’s economy has generally grown at galloping rates of between 5% and 10%. In the past decade, Kikwete has reduced the public debt load and boosted exports to India and China. Shortly after taking office, Kikwete received two boons — the cancellation of $640 million in public debt by the African Development Bank and a key set of agreements with China’s premier at the time, Wen Jiabao, to help develop the Tanzanian economy. As with his predecessors, Kikwete hasn’t avoided the whiff of corruption, though in 2008 it was Lowassa himself who was at the heart of the scandal. More recently, after Kikwete’s 2010 reelection, he welcomed Chinese president Xi Jinping to the country in March 2013 and oversaw the 50th anniversary of the Tanganyika-Zanzibar union.

Voters will also elect the 357 members of the Bunge la Tanzania, the country’s unicameral parliament. The CCM currently holds 265 seats, while Chadema holds 49 and the CUF holds 35. With the two opposition parties joining efforts to pry away the presidency from the CCM, they will almost certainly both reap record-making gains in the parliamentary elections as well.