After leading the polls in July, August and much of September, the New Democratic Party (NDP) now seems likely to place third after next Monday’s election.![]()

Much of the NDP’s fall is attributable to the corresponding rise of support for the Liberal Party under the leadership of Justin Trudeau, who spent much of the summer languishing in third place. Not so long ago, Mulcair appeared the favorite among Canadian voters to become the next prime minister. Today, however, polls suggest he will not only fall short of government, he’ll fall back from opposition leader to third-party status.

How did the NDP end up in such a strong position, as recently as a month ago, and how did it and its leader, Thomas Mulcair, squander such a historic opportunity?

If you’re just tuning in, the conventional wisdom goes something like this:

- Liberal thumping in 2011: In the May 2011 election, the center-left Liberal Party, under its third leader in five years, fell to just 34 seats in the House of Commons, an absolutely disastrous effort for a party that spent most of the 20th century in power.

- Orange wave in 2011: In the same election, a wave of support for the more progressive New Democratic Party (NDP), most notably in Québec, where its leader Jack Layton won two-thirds of ridings (and dooming the once-dominant separatist Bloc québécois to just four seats) made the party, for the first time, the official opposition.

- Mulcair era begins in 2012: Layton’s death from cancer in August 2011 threatened to blunt the party’s momentum, despite the Mulcair’s election in March 2012 as the new NDP leader. A former provincial minister in Québec’s government and a member of the more centrist wing of the NDP, Mulcair was deemed most able to position the party as the moderate alternative to prime minister Stephen Harper and the Conservatives.

- Trudeau era begins in 2013: Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff, an academic, stepped down shortly after the election and after a nearly two-year interim leadership of Bob Rae (who himself served one term leading an NDP government in Ontario in the early 1990s), the party elected as its leader Justin Trudeau, the son of the mostly beloved late prime minister of the 1960s and 1970s, Pierre Trudeau.

- Liberals regain top spot nationally: Between Trudeau’s election in April 2013 and May 2015, the Liberals generally held a lead in polls, given the strength of the Trudeau name, and the youthful exuberance of its new leader, despite his often vacuous stands on policy. The NDP sank slowly back to third-place territory in polls.

- Alberta upset puts NDP on top: Amid tumbling oil prices, the Albertan provincial election in May 2015 swept a 44-year Progressive Conservative government out of office on the strength of a relatively business-friendly, capable government headed by Rachel Notley — the first NDP government in Alberta.

- Trudeau’s stumbles send him back to third place: Between May 2015 and September 2015, voters gave Mulcair and the NDP a second look, and they seemed to like what they saw. After months of ads from the Conservative Party decrying Trudeau as too inexperienced to become prime minister, Mulcair appeared a sensible alternative. Whereas Trudeau ultimately supported Harper’s controversial anti-terrorism Bill C-51, Mulcair and the NDP opposed it on the grounds that it violated personal and civil liberties. That initially had the effect of cementing left-leaning voters in the NDP camp.

That brought us well through the start of the autumn election campaign, with a consistent — if always narrow — NDP lead.

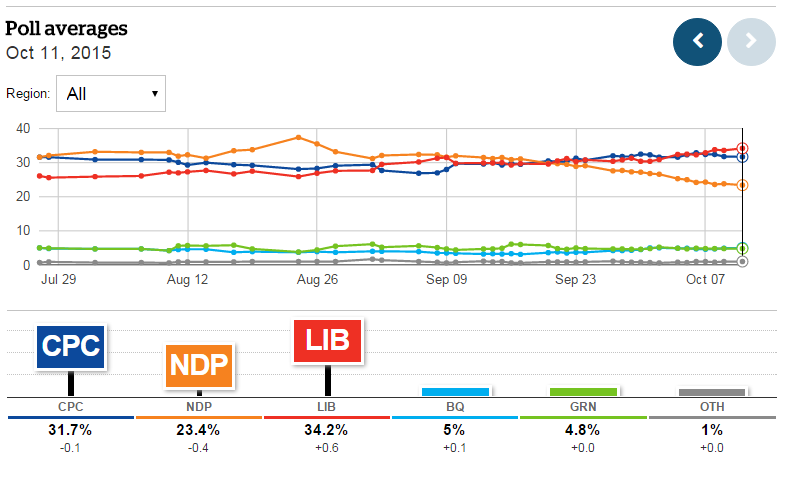

Though the picture is somewhat clouded by the nature of a first-past-the-post contest in 338 discrete ridings, it seems clear that the NDP is now struggling to hold onto the support it claimed earlier in the summer. Here’s the CBC’s poll tracker, as complied from an aggregate of national polls by ThreeHundredEight‘s Éric Grenier, as of October 11, nationally:

If the election were held today, the NDP would win around 80 seats, though the projections show that it could win as many as 122 (which would actually mean an increase from 2011) and as few as 35. The Liberals are now projected to be the big winners, with a projected 134 seats, and the Conservatives would hold onto 119 seats, down from the 166 they won in 2011. No party would win a majority. Barring snap elections, two parties (almost certainly the Liberals and the NDP) would have to form some kind of coalition or governing arrangement.

So how has everything changed so suddenly?

1. Trudeau outflanked Mulcair on the economy

As it became clear in August and September that Canada was entering a narrow recession, Trudeau, languishing in third place behind the NDP and the Tories, made his move — a pledge that he would engage in classical Keynesian deficit spending to boost employment and GDP growth at a time when the commodities price glut has so weakened Canada’s economy.

Mulcair’s strategy to continue to target balanced budgets was designed to reassure centrist voters that Canada’s first potential NDP government could be trusted on economic matters. But by playing things so safely (and hugging, in essence, the Tory position on deficit spending — and for that matter, the Liberal position in the 1990s and early 2000s), Mulcair came to be seen as the less progressive option vis-à-vis Trudeau. It didn’t help that ‘Tom Mulcair’ was viewed, rightly or wrongly, as saying one thing to voters in English and ‘Thomas Mulcair’ viewed as saying another in French.

With the Green Party’s leader, Elizabeth May, castigating both the Liberals and the NDP for their stands on environmental matters, and with Mulcair bogged down in cultural debates in Québec, Trudeau’s stand on deficit standing became the keystone issue that set him apart from both Mulcair and Harper on the economy. In the span of a couple of weeks, the Liberals re-emerged in first place in the polls as the NDP began its slow sink back down to third.

In the next six days, Mulcair will cross the country attacking Harper for finalizing the Trans-Pacific Partnership and alleging that Trudeau will ultimately support the trade pact. Focusing on the TPP could boost the NDP among manufacturing workers, especially in Ontario and Québec, and Trudeau has hedged his bets, embracing a pro-trade outlooks without necessarily supporting the TPP. But it may be too late for Mulcair to bring left-leaning voters back to the NDP camp so close to election day.

2. Mulcair got caught in the ‘niqab’ trap in Québec

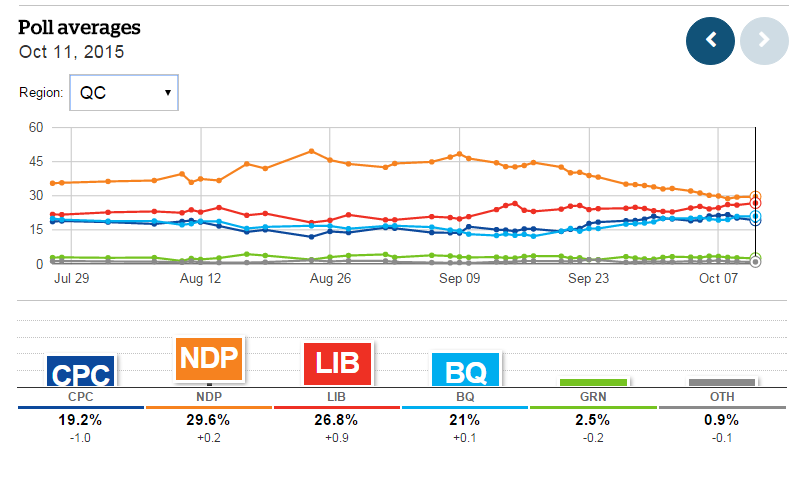

Meanwhile, in Québec, Mulcair’s noble stand in favor of allowing Muslim immigrants to continue to wear the niqab cost him voters, while the Bloc and the Tories used the issue to stir anti-Muslim sentiment. The result is that while the NDP still leads narrowly, it is set to lose some of the ridings that it won in 2011, mostly to the Liberals, but also to the Conservatives and, possibly, even the Bloc, once again under the leadership of Gilles Duceppe.

It’s all the more amazing when you consider that the NDP maintained its lead in Québec through even the tough years that followed Trudeau’s near-coronation as Liberal leader. Trudeau, after all, represents a riding in Québec, as did his father.

Here’s the poll tracker, as of October 11, in Québec, which shows just how damaging the niqab and deficit spending issues have been to the NDP, which has watched a 20-point lead evaporate to just three points — and that may fall further in the six days until election day:

3. Ontario was always the soft underbelly

of the 2015 ‘orange wave’ narrative

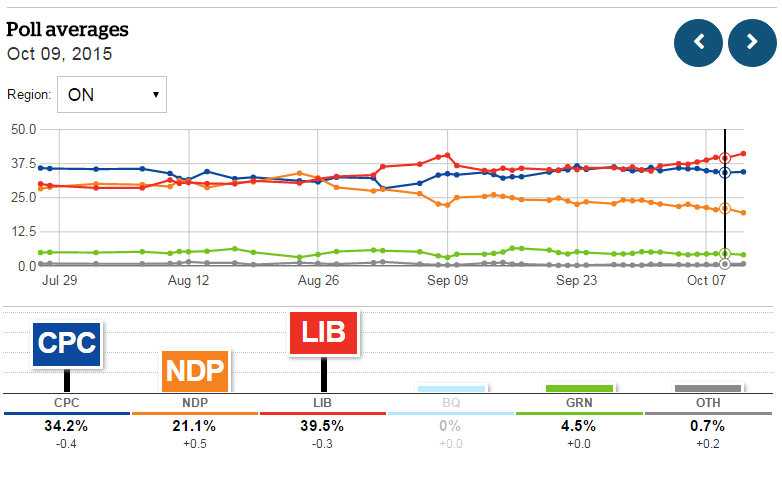

The NDP’s national lead always disguised the fact that it was playing defense in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, with 121 of the seats up for grabs in the expanded House of Commons.

Part of that may have had to do with the legacy of Bob Rae, who led an increasingly unpopular one-term government in the province between 1990 and 1994 (never mind that Rae subsequently joined the Liberals when he moved to federal politics and served for nearly two years as its interim leader).

But Ontario never really warmed to the NDP, even in the 2011 election, when the NDP won just 22 seats there (the Tories won 73, while the Liberals held onto just 11). Many rural ridings are as reliably Conservative as in western Canada. In downtown Toronto, the NDP was always going to have to compete with a longstanding Liberal tilt, and in the suburbs, Mulcair was already facing skepticism from the same voters that supported Rob Ford and Doug Ford in Toronto’s mayoral elections.

As the CBC’s poll tracker shows, the NDP was almost always tied or trailing in the province at the height of the national NDP swoon, and the Liberals would have certainly taken advantage of the NDP’s enduring weakness there, especially given the full-throated support of Ontario premier Kathleen Wynne for Trudeau’s campaign:

But it wasn’t just in Ontario. The Liberals have long held an advantage in the relatively poorer Atlantic Canada region. The strength of the Green Party drew voters away from the NDP in British Columbia (one reason why Adrian Dix’s seemingly unbeatable provincial campaign in 2013 lost to the BC Liberals). Manitoba’s premier, Greg Selinger, has led the province since 2009, and his unpopularity would have made an NDP win there difficult. Moreover, polls in Alberta have always shown the Conservatives with a strong lead, notwithstanding the wave that brought Notley and the Albertan NDP to power just five months ago.