Alexis Tspiras’s victory in Sunday’s snap elections in Greece is reminiscent of Richard Wagner’s four-opera marathon Ring cycle — at the end of hours of drama, the ring ends up more or less right where it began, with the Rhinemaidens.![]()

So it was in Greece, where voters have faced a tumultuous eight months under the first Tsipras government that began when Tspiras led the fiercely anti-austerity SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς) to a near-landslide win in January’s parliamentary elections.

Influenced by hardline academic Yanis Varoufakis, his initial finance minister, Tsipras tried (and failed) to extract concessions from European lenders with respect to the often harsh conditions tied to Greece’s first two bailouts. Back in January, Tsipras promised Greek voters that he would reduce the country’s austerity conditions while keeping Greece within the eurozone. However, with a looming default to the International Monetary Fund in late June, Tsipras called a July 5 referendum to give voters a chance to weigh in on the terms that eurozone finance ministers were offering Greece in exchange for extending its second bailout.

* * * * *

RELATED: Why this weekend’s election in Greece doesn’t really matter

* * * * *

Though Tsipras won a resounding “No/Oxi” against the bailout deal, the political victory came at a cost. His government was forced to introduce capital controls within hours of calling the referendum, and Greece officially defaulted on its IMF payment. During the nine-day referendum campaign, Greece’s financial condition deteriorated so much that Greece faced its most serious risk in five years of being pushed out of the eurozone. Dismissing Varoufakis in favor of the more moderate Euclid Tsakalotos, Tsipras reversed course and ultimately entered talks for a third bailout of €86 billion, with at least a vague, face-saving promise to consider debt relief later this year. The new bailout, in turn, led to a massive rebellion within SYRIZA, so much so that Tsipras needed opposition support to enact the key parliamentary votes on the third bailout. By the end of the summer, former energy minister Panagiotis Lafazanis and 24 far-left SYRIZA MPs, including the fiery parliamentary speaker Zoe Konstantopoulou, split into a new party, Popular Unity (LE, Λαϊκή Ενότητα), dedicated to reintroducing the drachma.

As a result, Tsipras called snap elections for September 20 as a way of winning an electoral mandate for his considerable volte face and as a way of consolidating his control over the increasingly centrist SYRIZA, purged of its far-left wing.

So, after all of that, what happened?

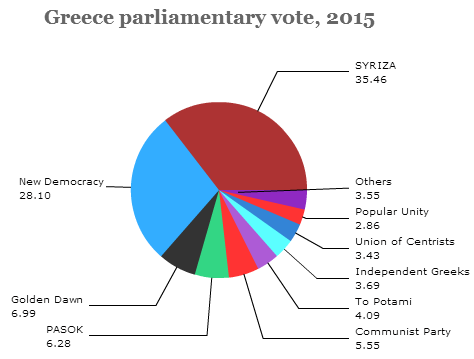

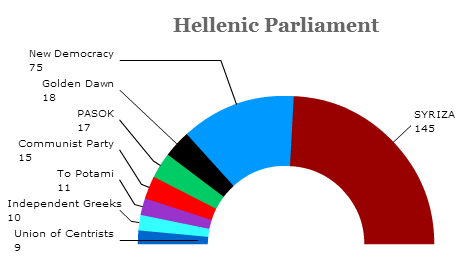

Not much. Despite a turnout that was around 800,000 lower than in January, the end result was a Hellenic parliament that now looks almost exactly the same as it did when Tsipras resigned late last month to call elections. Defying polls that showed SYRIZA tied with the center-right New Democracy (ND, Νέα Δημοκρατία), Tsipras’s party (newly purged of its anti-bailout rebels) defeated ND by a margin of over 7% — SYRIZA lost just 0.88% support versus the January result, ND gained merely 0.29%.

That was enough for SYRIZA to win 145 seats, just a loss of four from January, and strong enough that Tsipras will continue to govern with the same junior partner, the ‘anti-austerity,’ right-wing nationalist Independent Greeks (ANEL, Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες). Despite fears that ANEL’s support would fall below the 3% threshold to enter parliament, the party cleared the hurdle and will lose just seven seats.

Together, it’s enough for a fragile majority, but the best news for Tsipras is that the SYRIZA rebels in Popular Unity fell just short of the 3% hurdle.

What does that mean for Greece’s future?

Tsipras is committed to implementing the third bailout and, indeed, some of the VAT increases will take effect in early October. With New Democracy and the center-left PASOK (

Given that so much of Greece’s fiscal policy is now dictated by Brussels and Berlin, the election wasn’t really about whether Greek voters wanted to choose a far-left progressive government or a conservative government. Instead, voters were choosing which team that it prefers to implement the terms of the latest bailout deal.

Perhaps Greeks simply believed that, having negotiated the third bailout, Tsipras should be forced to carry it through (and many European policymakers believed that had Tsipras lost, he would eventually turn against the bailout, comfortable from the opposition benches). Given a fresh mandate from the electorate and a more compliant SYRIZA caucus, Tsipras will have clear responsibility for his second government’s results.

Tsipras is also relatively popular, despite the fact that he appears to have broken just about every promise he made in January and immediately switched his position in July on a new bailout. But it may be that Greeks also realize that Tsipras worked as hard as possible (right to the brink of Grexit) to get better terms for his country. Indeed, he may have won, at long last, a discussion on debt relief. It may not have been worth the collateral damage to the economy, wiping out what seemed like a nascent recovery last year, but voters appear to be giving Tsipras credit for fighting so hard for relief from Greece’s creditors.

However, Greeks also seemed reluctant to turn power back to the old elites. Though PASOK recovered a little support yesterday, the two traditional parties, PASOK and New Democracy, still won just over 34% cumulatively — down from around 80% in 2007. New Democracy’s interim leader since July, Vangelis Meimarakis, has worked credibly to pull the party to the center, and he argued throughout the campaign that he would try to build a grand coalition, open to including SYRIZA if he won the election. Though Meimarakis is more popular than former prime minister Anotnis Samaras, he’s still the son of an MP and represents the entrenched political aristocracy that has controlled Greek government since before the military junta of 1967-74. Greeks may not be thrilled with Tsipras’s first eight months, but they believe political newcomers will do a better job than a corrupt and longstanding elite.