The hand-wringing about Turkish democracy turned out to be overwrought — electoral churn is alive and well, despite the efforts of its president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, to consolidate the power of his ruling party, the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party).![]()

For the first time since the AKP came to power in 2002, Erdoğan wasn’t technically leading the party after winning the presidency last year. Nevertheless, his presence was clear enough in the weeks leading up to the vote, threatening journalists and campaigning openly in defiance of the traditional independence of the office of the presidency, which Erdoğan hoped to strengthen significantly by changing Turkey’s constitution.

* * * * *

RELATED: Turkish election a referendum on

Erdoğan-style presidentialism

RELATED: Who is Selahattin Demirtaş?

* * * * *

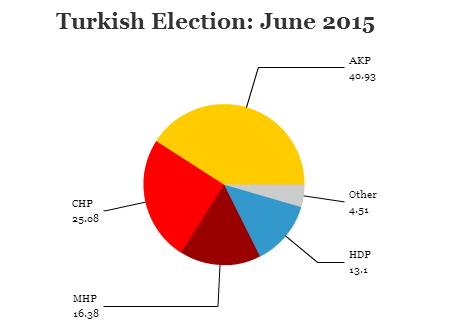

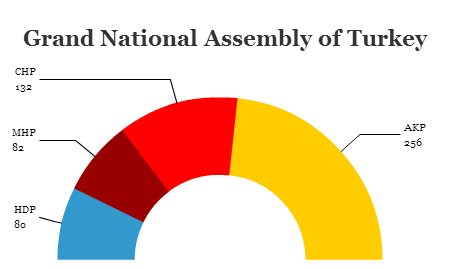

Erdoğan hoped to win the 330 seats necessary to initiate constitutional changes to shift power permanently to the presidency and away from the assembly. Instead, the AKP fell to just 256 seats, 20 short of a majority. While that’s enough for the AKP to remain the largest party, by far, in the Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (Grand National Assembly), voters rewarded Erdoğan’s overreach by forcing the AKP to seek a coalition partner, a novelty after nearly a decade and a half of one-party rule.

Accordingly, the results bring more questions than answers. Though the election is probably good for the long-term stability of Turkish democracy, the result could mean a considerable amount of short-term instability, a prospect that’s already spooked Turkish markets this morning.

For the first time in Turkish history, an explicitly Kurdish party will hold seats (as a party) in the Turkish parliament. It’s a great opportunity for political pluralism, but it also brings risks. If Erdoğan turns too sharply against his Kurdish rivals, he could tragically damage the strengthening trust that he’s built over the past decade between the Kurdish minority and the Turkish government.

Prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, Erdoğan’s former foreign minister, had pledged to resign in the event that the AKP failed to win enough seats to form a government, so his future is very much in question. If he goes, Erdoğan will be hard-pressed to find a reliable ally who satisfies both wings of the AKP and who will also govern in deference to Erdoğan’s wishes.

Moreover, shifting to coalition politics will prove difficult for the AKP, most especially Erdoğan. Even if he manages to find a junior coalition partner, Erdoğan might be anxious to hold new elections to restore the party’s majority. As much as the June 7 elections affirmed the resilience of Turkish democracy, snap elections might prove an even more serious test if Erdoğan is willing to resort to extralegal steps — especially after he flouted presidential impartiality and the AKP devoted significant state resources to its election victory.

Erdoğan, over the years, has gradually consolidated authority into a narrowing group of advisers, to the point that he’s sidelined senior AKP figures, including co-founders like deputy prime minister Bülent Arınç and former president Abdullah Gül, who might otherwise challenge his authority. Increasingly, Erdoğan gradually shifted away from democratic best practices that emphasize liberal freedoms and consensus-building. Turkish voters are also becoming impatient with a slowing economy after years of booming expansion.

The clearest winner of the election was the Halkların Demokratik Partisi (HDP, People’s Democratic Party), a merger of several left-wing groups and the Kurdish Democratic Regions Party, and its charismatic co-chair, Selahattin Demirtaş, a 42-year-old Kurdish human rights attorney. Given that Turkey has the world’s highest parliamentary threshold (10%), his decision to contest the general elections as a party (and not, as in years past, with a slate of independent candidates) wasn’t without risk. The HDP easily surpassed the 10% mark by appealing beyond the Kurdish minority, but that’s not guaranteed in the future.

Nevertheless, the victory marks an inflection point as Turkish Kurds address lengthy grievances about minority rights through the Turkish political system and not, as in the 1980s and 1990s, through armed guerrilla warfare. The HDP’s success likely deprived the AKP of 80 seats it otherwise might have easily expected to win, and that’s ironically a result of the Kurdish political integration that represents one of Erdoğan’s most important legacies. Under Erdoğan, restrictions on the use of Kurdish language were relaxed or eliminated altogether, and he has joined peace talks with the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, Kurdistan Workers’ Party), an armed Marxist group led by the imprisoned Abdullah Öcalan.

Make no mistake, however — the AKP remains the most dominant political force in Turkey today, and it dominated the election across the Anatolian heartland and even in the urban centers of Istanbul and Ankara. Despite growing enthusiasm for Demirtaş’s social democratic vision for a more liberal Turkey, the HDP is still just the fourth-largest party. The Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party), Turkey’s chief opposition party, actually lost support compared to the 2011 elections, with stale policies, listless leadership and a sense that it’s still too tied to the corrupt, military-backed Kemalist regime that preceded Erdoğan. It struggled to expand beyond its strongholds along the Aegean coastline.

Each of the opposition parties have, to varying degrees, ruled out coalitions. But that will almost certainly change in the days ahead.

The AKP’s most likely coalition partner is the right-wing Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP, Nationalist Movement Party). The party has its roots in secular, right-wing Turkish ethnocentrism, and it has an ugly and sometimes violent past, with a youth organization, the Grey Wolves, that arguably functions as a paramilitary unit. Since 1997, when Devlet Bahçeli assumed the party leadership, however, the MHP has moderated somewhat and assumed a more Islamist mantle. It joined forces with the CHP to support a consensus opposition candidate in last summer’s presidential election, and Bahçeli (pictured above) himself served as a deputy prime minister in a coalition government between 1999 and 2002. Though Demirtaş may have made the largest splash during the campaign, it’s now Bahçeli who is in position to shape the tone of Turkey’s sudden turn to a new coalition-based politics.

Bahçeli has made it clear that his party’s support is available only through a formal coalition, not an informal arrangement to bolster an AKP minority government. Turkish Kurds will worry that if Erdoğan brings the MHP into power, it will mean a freeze on the peace talks, which the MHP strongly opposes, and a return to anti-Kurdish policies. Moreover, a deal with the MHP would force Erdoğan to abandon his plans for a more powerful presidency, a price that Erdoğan may not be willing to pay.

If those coalition talks fail, it’s hard to believe that the AKP would form a coalition with either the CHP or the HDP. Demirtaş, whose appeal lies in projecting himself as a charismatic anti-Erdoğan, ruled out a coalition during the election campaign. Lacking a credible coalition partner, Erdoğan could call elections within 45 days. It’s not quite clear who would benefit from a second vote, however — the AKP’s opponents have a credible case that they’ve pierced Erdoğan’s seeming invulnerability, establishing fresh expectations among Turkish voters for a post-AKP government.

That’s a far cry from last year’s presidential election, where pro-Erdoğan posters made it clear that the AKP hoped to be in power for a century or more — or at least in 2023, the centennial anniversary of the modern Turkish republic’s founding, and far beyond.