When she was elected in September 2013 as Norway’s new conservative prime minister, one of Erna Solberg’s top priorities was to bring down the value of the Norwegian currency, the krone.![]()

Boosted by its spectacular oil wealth, Norway is today one of the world’s wealthiest countries, so strong that it’s shunned not only eurozone membership but accession to the European Union altogether. Like many other oil-producing countries, however, the sudden drop of oil prices since July from over $100 per barrel to nearly $60 today has adversely affected Norway’s economy. If prices drop even lower, or the $60 level sustains itself through 2015 or beyond, it could endanger Solberg politically, who leads a minority government consisting of her own center-right Høyre (the ‘Right,’ or the Conservative Party) and the more controversial Framskrittspartiet (Progress Party), a more populist, anti-immigrant party that has its roots in the anti-tax movement. The Progress Party’s leader, Siv Jensen, now holds the unenviable task of serving as Norway’s finance minister as oil prices tumble. Solberg ousted the popular two-term prime minister Jens Stoltenberg, who is now NATO secretary-general.

But for a country that was facing inflationary pressure when the rest of Europe continues to battle deflation, the fall in oil prices may bring additional benefits to a country long topping the list of the world’s most expensive places. As of July 2014, Norway still led The Economist‘s ‘Big Mac Index‘ — the price of the iconic McDonald’s sandwich was a whopping 61% higher in Norway than in the United States.

There’s no doubt that a sustained fall in oil prices will harm Norway’s bottom line. It will reduce the revenues available for public spending (already estimated to fall by over $9 billion because of the price drop), and it could easily cause Norwegian GDP growth to fall in 2015 from estimates of 2% or so (still robust compared to the eurozone), thereby causing the country’s relatively low 3.4% jobless rate to climb.

But it’s also caused the krone to fall to a 13-year low, declining to parity with neighboring Sweden’s currency, the krona, for the first time since 2000. As recently as May, one US dollar was worth 5.8 Norwegian kroner. Today, that’s skyrocketed to 7.5 kroner and, as Russia and other oil-exporting countries see their own currencies tanking, investors could push the krone even lower.

Aside from reducing concerns about inflation, the krone‘s fall could provide all kinds of benefits to Norway. For now, Solberg remains incredibly popular with Norwegians. Also for now, Jensen and the government doesn’t seem panicked, though the central bank cut interest rates from 1.5% to 1.25% last week. The current 2015 budget cuts taxes, while holding social welfare spending steady and increasingly spending on the country’s infrastructure.

For shopkeepers along the country’s eastern border with Sweden, it means that Norwegian consumers will stop crossing into Sweden to buy regular goods and services, boosting the local economy at Sweden’s expense. It will also make Norway’s exports cheaper in Europe and elsewhere abroad. Though 60% of the country’s exports are energy-related, the weaker currency will give Norway’s manufacturing and fisheries sectors a chance to become much more competitive. Those sectors have stagnated since 1969, when North Sea oil deposits were first discovered, starting an economic boom that’s delivered fabulous wealth to the Nordic country for decades — so much so that most of the oil revenues have been stashed away in Norway’s oil wealth fund, which now amounts to the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund with just under $890 billion in assets.

Tourists from the United States, Europe and elsewhere in the developed world who travel to Norway for its pristine wilderness and beautiful coastal fjords will have a little less sticker shock at the prices in Oslo and Bergen as the krone‘s value drops further.

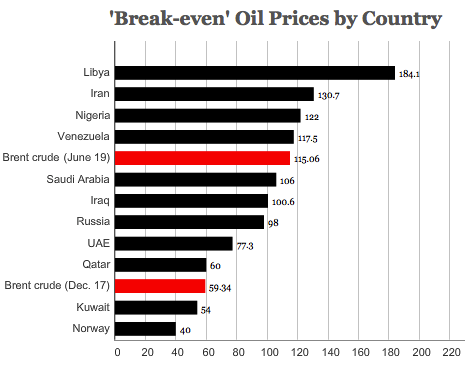

Despite the pressure from the populist left and right to spend more of the oil wealth fund on annual budgets, Norway’s traditionally cautious governments on both sides of the ideological spectrum have managed their resource-driven windfalls in nearly textbook-perfect fashion. Among the world’s oil producing countries, Norway’s ‘break-even’ point (the oil price at which it can no longer balance its budget) is just $40 per barrel — much lower than countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar that have amassed sizable reserves and far, far lower than countries like Russia, Iran and Venezuela, each of which is teetering on the brink of economic crisis.

An economic boom left Norway and its 5.085 million people with a wealth fund so massive that experts say it could benefit from being split into two or three smaller competing funds. That boom, for now, seems to be ending. Of course that’s not the best news. But to the extent that Norway’s oil boom was eventually going to end, the country’s sharp investment and savings have left it a winner in relative terms, and a pause in sky-high oil prices will also give it distinct absolute advantages.

Er…Norways fund is massive because that is where ALL the oil income goes. While dividents of fund investment goes into the budget, the oil income does not. Hasn’t for decades.

The budget is therefore unaffected by the oil price. A very low oil price will have knock-on effects, of course, as a lot of economic activity and employment supports the oil, but that will also strengthen the other export industries.