Photo credit to Reuters / Toby Chang.

Photo credit to Reuters / Toby Chang.

In Hong Kong, they may be protesting with umbrellas, but in Taiwan earlier this year, it was sunflowers.![]()

![]()

![]()

As Beijing locks itself into what now seems like a needless showdown with the pro-democracy activists who have formed Hong Kong’s ‘Occupy Central with Peace and Love,’ among the chief incentives for proceeding with caution are mainland China’s relations with the Republic of China (ROC), the island of Taiwan, which split from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 in the aftermath of the Chinese civil war and which has maintained its de facto sovereignty ever since, to the annoyance of decades of Chinese leadership.

* * * * *

RELATED: Hong Kong — one country, one-and-a-half systems?

* * * * *

Even as Western commentators trot out tired comparisons to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and crackdown (at a time when Hong Kong’s British colonial governors were not prioritizing democratization in any form), the Hong Kong protests have a readier comparison to the ‘Sunflower Student’ movement in Taiwan earlier this spring, when another group of protesters demonstrated against closer ties between Taiwan and the PRC.

In June 2013, Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) and the ruling Kuomintang (中國國民黨) signed the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement with mainland China, which would liberalize trade in services between Beijing and Taipei, including, most controversially, tourism, finance and communications. When Ma (pictured above) tried to push the CSSTA through the Taiwanese legislature without as much political deliberation as promised, an already skeptical Taiwanese opposition howled, and CSSTA protesters occupied the Legislative Yuan (立法院) to stop Ma’s push to ratify the agreement. Today, Taiwan’s legislature still hasn’t approved the CSSTA.

Moreover, Ma came out in favor of the Hong Kong protests on Monday and reiterated earlier this week his opposition to reunification with mainland China:

“We fully understand and support Hong Kong people in their call for full universal suffrage,” Ma told a gathering of business leaders in Taipei.

“Developments in Hong Kong have drawn the close attention of the world in the past few days. Our government has also been very concerned,” he added. “We urge the mainland authorities to listen to the voice of Hong Kong people and use peaceful and cautious measures to handle these issues.”

Cross-Straits relations have crested and ebbed over the last 65 years, but today it’s indisputable that Taiwan and mainland China have more ties than ever. Since 2008, direct flights between Taiwan and China have greatly intertwined the two economies, and a deluge of Chinese investment has taken root in Taiwan.

While Hong Kong and Taiwan have very different histories and relationships with the PRC, they share many similarities, so it’s not surprising to see so many similarities between the two popular anti-Beijing movements that swept across both jurisdictions in 2014.

In the second half of the 20th century, Taiwan and Hong Kong both became magnets for defectors from the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党), and both Taiwan and Hong Kong became pockets of economic prosperity while mainland China languished under Mao Zedong (毛泽东) and his fearsome reign of socialism, rural famine and political terror. Throughout, both Hong Kong and Taiwan developed particular cultural identities, such that majorities in both places see themselves today as Hong Kongers and Taiwanese rather than Chinese.

Both Hong Kongers and Taiwanese also worry that Beijing is plotting to bring Hong Kong and Taiwan more firmly within its grasp. If it’s outlandish to think that Beijing can accomplish that goal with military might, it’s not difficult to believe it can do so through economic and political coercion. That’s exactly the kind of insidious influence that motivates both the Occupy Central’s fight for Hong Kong’s democratic sovereignty and the Sunflower Student movement’s fight for Taiwan’s economic sovereignty.

In the 1970s, many countries, including the United States in 1979, ceased to recognize the ROC as China’s official government, and the PRC assumed China’s United Nations Security Council seat in 1971. Today, less than two dozen states — an eclectic mix of mostly Central American, African and Pacific island countries — still maintain formal diplomatic relations with the ROC, a testament to the growing economic and political clout of mainland China in the 1970s and 1980. While the United States continues to treat Taiwan as a de facto state and further, one of its leading east Asian allies, engaging in high-level cooperation on military, economic and geopolitical matters alike, it’s hard to believe that the US resolve still exists to defend Taiwan’s sovereignty at any cost, even though it was a bedrock principle of US foreign policy as recently as the George W. Bush administration.

Following Taiwan’s transition from a one-party system ruled by the Kuomintang to a multi-party democracy in the early 1990s, politics are dominated by views on relations with mainland China.

The Pan-Blue Coalition is led by the Kuomintang, the party founded in 1911 by the first president of China’s short-lived republic, Sun Yat-sen (孫文). The Kuomintang today is generally keener on developing closer trade and other ties with mainland China, though it doesn’t support reunification with mainland China on the kind of ‘one country, two systems’ approach that currently governs Hong Kong and Macau.

The Pan-Green Coalition is led by the main opposition party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民主進步黨), founded in 1986. It favors eventual Taiwanese independence and remains much more suspicious of mainland Chinese designs on Taiwan. Its somewhat convoluted position that Taiwan is already independent means that it can gingerly avoid declaring independence, which could trigger a military response from the PRC. Nevertheless, the DPP is already calling for a firmer Taiwanese statement on the Hong Kong situation.

Hong Kong became a British colony in 1841, and it returned to Chinese sovereignty only in 1997. Under the principle of ‘one country, two systems,’ Hong Kong is governed by a Basic Law that guarantees a much more liberal set of personal and political freedoms than Chinese citizens enjoy on the mainland, an independent judicial system and financial institutions and, as of 2017, the right to direct suffrage in choosing Hong Kong’s chief executive. The current protests stems from disagreements with Beijing over the nature of the 2017 elections — PRC officials are adamant that they should control the nominating procedures, while activists want a freer process that might allow, conceivably, the election of a relatively anti-Beijing chief executive. Beijing released a provocative white paper earlier this year maintaining its ‘complete jurisdiction’ over Hong Kong, which only fueled the growing pro-democracy protests.

Taiwan prospered under the Qing dynasty in the 19th century, but it fell into Japanese hands in 1895, and it remained under Japanese control until the end of World War II. When Chinese nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣中正) lost the country’s civil war to Mao and the Chinese communists, Chiang fled to Taiwan and established the ROC government.

In 1992, the ROC and PRC governments reached a pro forma consensus over what’s known as the ‘One China’ principle. Though both governments may agree that there’s one China, they still have radically different views about what China represents. Moreover, the 1992 talks took place as Taiwan was preparing for its first direct presidential elections in 1996.

So when British authorities effected the handover of Hong Kong to Chinese authorities in 1997 — and, to a lesser degree, when Portuguese officials effected the handover of Macau in 1999 — CCP officials knew that a rapidly democratizing Taiwan was watching closely. If mainland China didn’t respect the terms of deal struck with Hong Kong, which committed to the ‘one country, it might be harder to convince Taiwan to rejoin mainland China one day in the future.

In the 2000 elections, Taiwanese voters elected Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), a member of the opposition DPP, as its president, and they narrowly reelected him in 2004. Chen’s administration faced strong opposition from the Kuomintang, however, and almost as soon as he left office, he was found guilty of corruption and sentenced to life in prison in what many Taiwanese suspect to have been a politically motivated trial. But he kept relations with Beijing remarkably frostier than Ma, his successor.

A former mayor of Taipei, Ma led the Kuomintang back to power with his election in 2008 and reelection in 2012, and he’s jump-started the process of establishing stronger ties with mainland China. Today, Taiwan now sends around 40% of its exports to China (including Hong Kong) and just 10% to the United States.

Taiwan and Hong Kong are still far wealthier than the PRC. Taiwan has a GDP per capita of nearly $21,000, and Hong Kong’s per-capita GDP is around $38,000, compared to just $6,800 for mainland China. But that obscures the disparity between fast-growing supercities like the export-driven Guangzhou/Shenzhen corridor and Shanghai, with its resurgent financial clout.

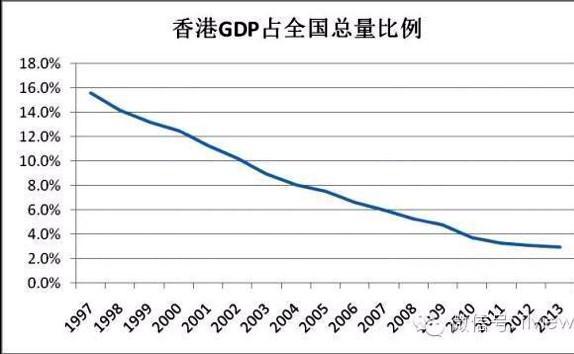

It also belies the fact that it is becoming more difficult for either Taiwan or Hong Kong to avoid interdependence with the far larger Chinese economy. Even if China’s growth slows in the years ahead, it is almost certain to become the world’s largest economy within a decade. As Ian Bremmer noted on Twitter earlier this week, Hong Kong’s share of Chinese GDP shrank from around 16% in 1997 to just 2.5% today:

China still has much to lose by tear-gassing protesters in downtown Hong Kong, because it remains a more important global financial center — even more (for now) than Tokyo, Shanghai or Singapore. Much of Hong Kong’s economic strength is that it provides a safer shelter for Chinese assets in the context of more robust regulatory and more transparent legal systems. Moreover, despite Beijing’s missteps, there are a handful of ways that CCP officials could ameliorate the situation. One path would be to replace Leung Chun-ying (梁振英), the unpopular chief minister selected in 2012 with a more amenable figure — perhaps the Shanghai-born Anson Chan, who served as Hong Kong’s chief administrative official in the final four years of British rule and the first four years of Chinese rule. Leung is dogged by allegations that he made illegal improvements to his home without obtaining the correct permits, so his forced resignation would dovetail nicely with the anti-corruption purge that president Xi Jinping (习近平) has pursued since taking office in 2013.

But Hong Kong’s protesters know as well as PRC policymakers that Taiwan is still watching very closely, and Beijing’s wrong-footed response in Hong Kong today could halt Ma’s push for greater Taiwanese cooperation and, ultimately, postpone reunification talks with Taiwan for years.