Ultimately, neither Gulenists nor Kemalists nor anyone else could stand in the way of Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in his quest to become Turkey’s first directly elected president. ![]()

But his victory in yesterday’s presidential election wasn’t exactly surprising — the only question was whether Erdoğan (pictured above) would win the presidency outright on August 10 or whether he would advance to a potential August 24 runoff against the second-place challenger, former diplomat Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu.

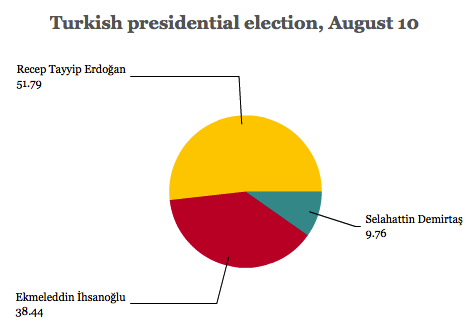

As it turns out, Erdoğan narrowly won in the first round with around 51.79% of the vote:

Though the election’s outcome wasn’t really in doubt, Erdoğan’s future and the direction of Turkey’s political structure remain much cloudier. Vowing a ‘new era’ in his victory speech, Erdoğan’s ambition to remain the most powerful figure in Turkish politics is hardly a secret, even though the presidency has been a ceremonial office since the 1961 constitution. That means his presidential victory now presents at least three difficult questions for which we won’t have answers anytime soon.

* * * * *

RELATED: Can Erdoğan be stopped in

first direct Turkish presidential election?

* * * * *

In light of Turkey’s role as a key fulcrum in international affairs, straddling the European Union to the west, with which it shares a custom union, and increasingly exerting its influence in the Middle East to the east, with mixed effect in Iraq, Syria and Iraqi Kurdistan.

Will the AKP accede to Erdoğan’s presidential plans?

The first question is whether Erdoğan’s grip on the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) will remain strong enough to install a new party leader and a new prime minister of his own choosing. As president, Erdoğan will have to officially distance himself from his party. Notwithstanding the presidential mandate that he can now claim, Erdoğan could still face internal resistance from party leaders, including outgoing president Abdullah Gül and others who don’t necessarily want to facilitate the rise of Putin-style autocracy in Turkey. Gül has emphasized the rule of law and democratic institutions, as have allies like Ali Babacan, the deputy prime minister widely credited as the architect of the country’s current economic boom.

The first indication will come on August 27, when the AKP will hold a convention to elect its new leader, which comes one day before the presidential handover from Gül to Erdoğan. It’s seen as way to prevent Gül from running immediately for the leadership — and because Gül is not a deputy in the Turkish parliament, he can’t immediately be appointed prime minister either.

Nevertheless, if Gül truly wants the leadership or the premiership, it might be difficult for Erdoğan to deny it to a figure who founded the AKP alongside Erdoğan, who served as foreign minister for four years before his indirect election to the presidency, and who is the most widely popular figure in the AKP after Erdoğan. But it’s Erdoğan, as president, who will appoint the next prime minister.

Even if Erdoğan succeeds in appointing a more pliant ally like foreign minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, who certainly seems like the current frontrunner, there’s no guarantee that Davutoğlu wouldn’t eventually challenge Erdoğan. Even without the premiership, Gül and his allies will almost certainly form a significant counterweight to Erdoğan within the AKP.

Erdoğan’s transition to the presidency won’t come without risks, especially if the AKP believes that its long-term prospects lie in restraining Erdoğan from wielding greater power. After all, if he wins reelection, Erdoğan would retire in 2024, 22 years after first winning power. It might not be an arrangement that ambitious AKP ministers completely support.

Even if Erdoğan wields de facto control, can he effect

a de jure transfer of power to the Turkish presidency?

Second, even if Erdoğan could rely on a cooperative AKP, it only means that he’ll become the de facto head of government. That doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s appetite for the kind of constitutional reforms that would make the presidency the de jure center of power in Turkey.

While Erdoğan believes Turkey should transition from a parliamentary system to a presidential system and, while he can take some steps to strengthen the presidency almost immediately under the current constitution, any truly lasting transformation would require constitutional amendments — and a two-thirds majority in the unicameral, 550-seat Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (Grand National Assembly of Turkey).

Right now, the AKP holds just 313 seats, far short of the two-thirds threshold. That means that Erdoğan must increase the AKP’s seats in elections due to be held before June 2015 or convince skeptical opposition politicians to cede what little power they have left under the current system.

Will voters in the upcoming general election endorse

Erdoğan’s view of the presidency?

Third, though Erdoğan’s first-round victory is an impressive mandate, 48% of Turkish voters still voted for someone else. Even though Erdoğan enjoyed much more widespread media coverage than his two chief rivals and has otherwise benefitted from controlling Turkey’s state institutions as prime minister for the past 11 years, and even though his opponents were ill-suited to challenge him, he barely won an absolute majority in a country where voters have become increasingly worried about Erdoğan’s growing authoritarian (and Islamist) streak.

İhsanoğlu, a relatively little-known figure who headed the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation for a decade, was the conservative joint candidate of an awkward alliance between the center-left, formerly Kemalist Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party) and the ultranationalist, conservative Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP, Nationalist Movement Party).

Selahattin Demirtaş, the candidate of the Kurdish-based Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi (BDP, Peace and Democracy Party), is a rising star in Turkish politics, but his share of the vote, nearly 10%, is seen as something of a success.

Though Erdoğan and the AKP may now push to bring forward parliamentary elections to maximize their electoral strength in the wake of Erdoğan’s presidential victory, the parliamentary vote will instead likely mirror March’s local elections. The AKP won those elections, including the mayoral elections in both Istanbul and Ankara, but its national vote share was just 42.87% — nearly 10% lower than Erdoğan’s presidential victory.

Though they didn’t run in a formal alliance in March, the CHP and the MHP, in aggregate, won 44.21% of the national vote. So far from winning a two-thirds supermajority, Erdoğan and the AKP might actually lose strength in the National Assembly after the next parliamentary elections. It’s not that a joint CHP/MHP government is today a real possibility. While there’s a theoretical majority among Erdoğan’s opponents, including conservative Gulenist Islamists, the rising Kurdish leadership and the remnants of the old military-backed, secular political elite, those groups mistrust each other as much as they mistrust Erdoğan and the AKP. But it’s almost as outlandish to believe that the Turkish electorate is prepared to hand Erdoğan such a blank check.

Though seats are awarded on the basis of proportional representation, the AKP’s grip on power comes from the Anatolian heartland. You can see from the election map on Sunday’s presidential vote that the heavily Kurdish areas in the southeast supported Demirtaş, and though Erdoğan won both Ankara and Istanbul provinces, İhsanoğlu won Izmir province and otherwise defeated Erdoğan along the heavily developed Aegean and Mediterranean coasts:

All of which means that while Erdoğan’s presidential victory was so assured, we still won’t know for some time what that victory will mean for Erdoğan, the AKP and Turkey.

3 thoughts on “Erdogan wins first-round presidential victory”