You’ve probably never seen Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan like this before. ![]()

In his bid to win Turkey’s first-ever direct presidential election, he donned bright orange athletic gear (pictured above) and took to the football field at a new stadium in Istanbul earlier this week, scoring a hat trick against token opposition.

Though that may replicate Erdoğan’s seemingly unstoppable rise, leading his governing Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) to victory three consecutive times — in 2002, 2007 and 2011 — his latest electoral quest may prove more difficult.

Turkish voters will elect a president in voting scheduled for August 10 among Erdoğan and two challengers, Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu and Selahattin Demirtaş. If none of the candidates win more than 50% of the vote, the top two candidate will advance to an August 24 runoff.

The Cairo-born İhsanoğlu (pictured above), who served as the secretary-general of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation between 2004 and January 2014, is an academic with a background in, of all things, the history of science.

An independent by party and a conservative by temperament, İhsanoğlu was nominated for the presidency by an alliance of two very different opposition groups pushed together by a mutual opposition to Erdoğan: the center-left Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party), most associated with Kemalism in the pre-Erdoğan era, and the ultranationalist, conservative Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP, Nationalist Movement Party).

Demirtaş (pictured above), a 41-year old rising star popular among Turkish leftists, is the candidate of the Kurdish-interest Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi (BDP, Peace and Democracy Party), though he hopes to win support from among the CHP’s more liberal supporters.

Defying decades of repressive precedent, Erdoğan has tried to pacify relations between the central government and Turkey’s Kurdish minority, and he’s increasingly made Turkey an improbable ally of the de facto independent Iraqi Kurdistan. That’s won Erdoğan genuine respect among Kurdish voters, though many will undoubtedly support Demirtaş in the election’s first round. It will nonetheless be something of a curiosity if Erdoğan is forced into a runoff, but makes it over the top on the basis of Kurdish votes.

Today, most observers give Erdoğan the edge, but the prime minister has become such a polarizing figure, and his project to place the Turkish power firmly in the presidency such a controversial idea, that it could be much closer than anticipated. If Erdoğan fails to clear 50% and thereupon faces a direct challenge from İhsanoğlu later in August, the runoff will become a referendum on whether Turkey will essentially become not an Islamist or democratic or Kemalist state, but an ‘Erdoğan state.’

If İhsanoğlu wins, he will become, like many of his predecessors, a figurehead with ceremonial powers and little else.

If Erdoğan wins, in either round, he will almost certainly transform the Turkish presidency into a much more powerful office. Formerly, the president was appointed to a single, seven-year term by the Turkish parliament. Under the new system, the president is elected to a five-year term with possible reelection.

Erdoğan, Turkey’s prime minister since 2003, is arguably the most dominant Turkish politician in modern history after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the secular Turkish state in the 1920s and the 1930s.

When Atatürk held the presidency from the Republic of Turkey’s foundation in 1923 until his death in 1938, it was the powerful office that Erdoğan now hopes to restore. It was until the 1961 constitution’s promulgation that the office became largely ceremonial. The new constitutional order, which introduced checks and balances and ushered in an era of two-party democracy, followed the 1960 army coup against the ruling Democratic Party — the first of several military interventions in Turkish political life in the decades to come.

In leading the Islamist AKP to power in 2002, Erdoğan, formerly the mayor of Istanbul, fundamentally rearranged Turkish governance, with his mildly Islamist brand of politics overpowering the ‘Kemalist’ secular rule that previously barred any role for Islam in Turkish politics, and that had also empowered an increasingly corrupt and venal military elite.

Over the years, however, Erdoğan has increasingly turned to authoritarian means of pursuing his agenda by systematically weakening Turkey’s independent judiciary and otherwise reducing individual freedoms, notwithstanding the far-reaching economic boom unleashed over the past decade. Amid stalled negotiations for Turkey’s accession to the European Union, Erdoğan has instead turned eastward to transform Turkey into a key player in the politics of the Middle East.

Widespread protests last year, which began with Erdoğan’s decision to bulldoze Gezi Park in the middle of Istanbul in order to erect a new mosque, highlighted just how illiberal Erdoğan has become over the past decade. Critics worry that Erdoğan’s push to transform Turkey from a parliamentary system to a presidential system will accelerate the country’s growing authoritarianism.

Today, Erdoğan’s biggest threat no longer comes from the remnants of the Kemalist and military elite, but from the followers of Fethullah Gülen, a Turkish cleric based in Pennsylvania, whose movement, Hizmet (Turkish for ‘service’), became increasingly influential throughout the AKP’s 12-year rule. Gulenists are widely believed to have propelled sensational investigations into corruption and bribery that, last December, forced several members of Erdoğan’s cabinet to resign. Erdoğan has responded with a purge of Gulenists from many Turkish state institutions that shows no sign of abating anytime soon, replicating the strong-arm, paranoid tactics that characterized the ‘Ergenekon trials’ through which Erdoğan pursued, harassed and imprisoned former members of the military brass, as well as alongside CHP opposition figures and others.

Pressed from the Islamist right by the Gulenists with which Erdoğan once found common cause, and pressed from the secular left by protesters demanding the full rights and freedoms of a liberal democracy, Erdoğan’s magic touch on Turkish politics seemed in jeopardy by the middle of last year.

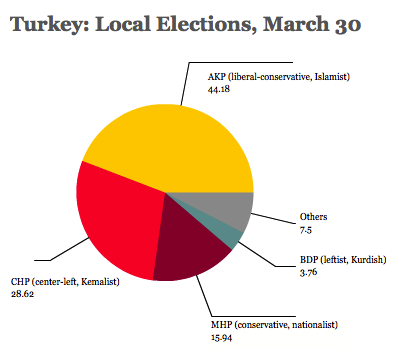

That changed earlier this spring when Erdoğan and the AKP powered its way to a strong finish in local elections, retaining the mayor’s office in Istanbul and (very narrowly) in Ankara, Turkey’s capital, though the CHP, with some credibility, alleged fraud int he Ankara race. Nationwide, the AKP outpaced its nearest challenger, the CHP, by a double-digit margin:

Nevertheless, in theory at least, a united CHP-MHP opposition front could command enough support to thwart the AKP, especially in a direct runoff scenario. Today, polls show that Erdoğan holds a slight double-digit lead over İhsanoğlu, with Demirtaş trailing in single digits.

If and when Erdoğan wins the Turkish presidency, the AKP must elect a new leader to lead it through the scheduled June 2015 parliamentary elections. Presumably, Erdoğan will want a pliant figure in the premiership who will defer to his wishes from the presidential palace at Çankaya, both before and after those next year’s general elections.

A year ago, everyone believed that the outgoing president, Abdullah Gül, who co-founded the AKP with Erdoğan, would switch places with the current prime minister. Gül (pictured above) is, by far, the most popular figure in the country after Erdoğan — and maybe more popular than Erdoğan. Gül, whose wife Hayrünnisa Gül caused something of a scandal when she decided to wear the traditional Muslim headscarf as first lady, is still somewhat mysterious in statements about his post-presidential plans.

Furthermore, with Erdoğan’s plans to drag power from the Turkish parliament to the presidency, he has now signaled that he might prefer another candidate to balancing power with a senior statesman like Gül. The most recent speculation has focused on foreign minister Ahmet Davutoğlu (pictured above), who has much less grassroots support, and shares blame for Turkey’s failures to broker peace deals in Syria or Gaza.

Ultimately, the shape and malleability of Turkey’s next prime minister and government will depend on whether the AKP is willing to stand up to Erdoğan. One prominent party leader, former deputy chair Dengir Mir Mehmet Fırat, recently resigned from the AKP, announcing his support for Demirtaş in the presidential race. Other AKP leaders, including possibly Gül, are less than enthusiastic about Erdoğan’s hopes consolidate power in the presidency, and they may be willing to stand up to him. Unshackled from the formalities of serving as head of state, Gül may believe it’s in the better long-term interests of the AKP’s project to try to limit Erdoğan.

Deputy prime minister Ali Babacan (pictured above), a Gül ally and one of the government’s chief architects of economic policy, noted last week that Turkey isn’t an ‘advanced democracy,’ and could be preparing to leave high office.

It’s still not certain that the AKP faithful will necessarily line up behind Erdoğan’s grand schemes for the Turkish presidency. The answer may ultimately have more to do with whether they believe Erdoğan’s plans will be a liability in the lead-up to the 2015 elections.

One thought on “Can Erdogan be stopped in first direct Turkish presidential election?”