Slovenians on Sunday turned over their country’s government to Miro Cerar, a political neophyte that barely anyone outside (or even inside) Slovenia had ever heard of a year ago.![]()

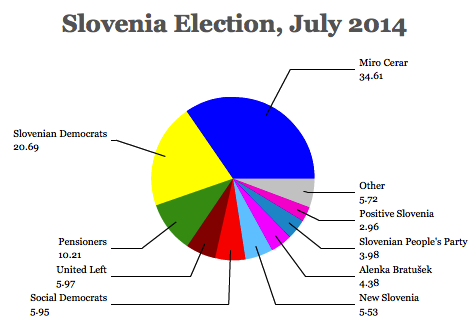

Cerar (pictured above), an attorney and law professor, and the son of an Olympic gymnast, formed the Stranka Mira Cerarja (SMC, Miro Cerar’s Party), barely a month ago. But that didn’t matter to Slovenians, and the SMC easily won the July 13 snap elections by a margin of 34.6% to 20.7% against the center-right center-right Slovenska demokratska stranka (SDS, Slovenian Democratic Party), whose leader, two-time prime minister Janez Janša, has been sentenced to two years in prison in relation to corruption charges. Cerar’s victory represents the strongest victory of any party in a Slovenian election since the return of Slovenian sovereignty in 1990.

Sunday’s snap parliamentary elections follow the resignation two months ago of Alenka Bratušek, Slovenia’s first female prime minister, after just over a year in office. Bratušek’s center-left coalition government is the second government since Slovenia’s last elections in December 2011.

* * * * *

RELATED: Bratušek, Slovenia’s first female prime minister, resigns

* * * * *

Cerar will now likely command 36 seats in the 90-member, unicameral Državni zbor (National Assembly), forcing him to form a coalition government with any of a number of allies in a National Assembly that remains fragmented, despite the strength of Cerar’s mandate.

Cerar’s success is in large part due to his novelty. He’s not tainted by the past six years of austerity or the past two decades of corruption that characterizes much of Slovenia’s political elite. He lies somewhat in the center or center-left of Slovenian politics, leaning right on the need for economic reform, but leaning left on the need for reconsidering some austerity-era policies that Cerar believes have harmed Slovenian growth. For example, he’s called into question several recent plans for privatizations, including the national telecommunications company and the corporation that run’s the national airport.

Slovenian analysts expect Cerar to turn to two parties to form what might become Slovenia’s strongest government in recent memory.

The first is the Demokratična stranka upokojencev Slovenije (DeSUS, Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia), a center-left pensionsers party that, with 10 seats, is also celebrating its best-ever result. Its leader, Karl Erjavec, has brought his party into coalition governments of both the left and the right over the past decade. Erjavec himself served as minister of defense under Janša between 2004 and 2008, and he most recently served as minister of foreign affairs under Bratušek. As the leader of the third-largest bloc in the new National Assembly, he’ll be a key player in coalition negotiations.

The second is the traditional party of Slovenia’s center-left, the Socialni demokrati (SD, Social Democrats), which fell from a high of 29 seats in 2008 to just six now, having taken the brunt of voter anger for economic turbulence during the 2011 elections.

Even so, Cerar will have to walk a fine line if he hopes to keep Slovenia’s budget deficit within 3% of GDP, per eurozone standards. Bratušek’s 13-month government successfully avoided a financial bailout, at the cost of further deep budget cuts. Though Cerar has pledged to keep Slovenia’s budget within the EU’s agreed parameters, he’s also stressed the need to make the public sector more efficient and the private sector more liberal.

A Central European spring?

Cerar joins a growing list of political novices who are gaining power across much of central and Eastern Europe. Six years on from the 2008 financial crisis, and four years on from the worst of the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis, European voters have now had opportunity to reject mainstream parties on the right and on the left, who are now both tainted with austerity-era policies that have saved their countries from bailouts and financial crises at the expense of high unemployment and lower growth potential.

Instead of turning to the fringes, voters are turning to the business world and to the academic world for alternatives.

In the October 2013 Czech parliamentary elections, voters turned to businessman Andrej Babiš, whose newly formed center-right Akce nespokojených občanů (ANO, Action of Dissatisfied Citizens) placed a very close second to the center-left Česká strana sociálně demokratická (ČSSD, Czech Social Democratic Party), enough to secure ANO’s participation in the Czech government, making Babiš the new Czech finance minister.

More recently, in March 2014, philanthropist and political newcomer Andrej Kiska easily defeated Robert Fico, Slovakia’s prime minister and the leader of the governing center-left Smer – sociálna demokracia (Direction — Social Democracy). Fico has largely withstood pressure to cut Slovakia’s budget, instead boosting spending on unemployment and promoting growth. Nonetheless, Slovakian voters feared handing the presidency, largely a ceremonial office, to such a powerful political leader.

In Italy, blogger and activist Beppe Grillo’s Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) essentially tied the two mainstream center-right and center-left forces in Italy’s February 2013 parliamentary elections with a strong anti-austerity platform.

In Bulgaria, the technocratic, center-left government of former finance minister Plamen Oresharski fell in June over the decision to stop construction on the South Stream gas pipeline from Russia under significant pressure from US and EU leadership. Accordingly, Bulgarians will vote on October 25 for a new government for the second time in 17 months after a largely lackluster election in May 2013 returned the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP, Българска социалистическа партия) to power after a five-year government headed by the center-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, Граждани за европейско развитие на България). Bulgarian Socialist leader Sergei Stanishev, however, didn’t assume the premiership after the weak Socialist victory, because of his unpopularity, stemming from his first term as prime minister from 2005 to 2009. But Stanishev is now locked in what will be a grueling battle with GERB’s leader, Boyko Borissov, prime minister from 2009 to 2013. Bulgarians, largely disenchanted with both Stanishev and Borissov, also seem ripe for a challenge from outside the political elite.

Snap elections backfire for Bratušek and Janković

Slovenia was one of the least affected by the bloody breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991-92, and accordingly, it was the first Balkan country admitted to the European Union in 2004, along with nine other Eastern and Central European countries. In 2007, Slovenia also became the first Balkan country to accede to the eurozone.

In the 2011 elections, Bratušek’s center-left party, Pozitivna Slovenija (PS, Positive Slovenia) played the role that Cerar’s party is playing today — a new, largely untainted center-left alternative. Founded by Zoran Janković, a businessman and the former and current mayor of Ljubljana, the Slovenian capital, it won the largest share of the vote in the 2011 elections as a protest vehicle. Nevertheless, Janez Janša, the leader of the center-right Slovenska demokratska stranka (SDS, Slovenian Democratic Party) instead formed a five-party coalition that kept Positive Slovenia in opposition.

When Janša’s government fell in 2013, due largely to a national investigation that unearthed massive corruption throughout the political elite, Janković and Janša were both deeply implicated. Accordingly, Bratušek became prime minister, leading another coalition government. The 2014 snap elections came as a result of Janković’s effort to retake the leadership of Positive Slovenia back from Bratušek.

That turns out to have been a disastrous mistake for both Janković and Bratušek, who left the part to form her own newly constructed Zavezništvo Alenke Bratušek (the Alliance of Alenka Bratušek). Positive Slovenia won just under 3% of the vote and no seats in the National Assembly, effectively ending Janković’s hopes for national office. Bratušek, however, managed to win 4.4% of the vote and four seats in the National Assembly. To some degree, that’s a validation of Bratušek’s decision to split from the corruption-plagued Janković, and her minor success reflects a small reservoir of goodwill among Slovenian voters for avoiding what would have been an embarrassing bailout. But it’s hard to see Bratušek playing a major role in the next government.

A new hard-left alliance, the Združena levica (United Left), a group of three labour and socialist parties, outpolled both Positive Slovenia and Bratušek’s alliance, winning six seats and nearly 6% of the vote.