The second round of Colombia’s presidential election has been billed as a momentous decision between war and peace.![]()

Juan Manuel Santos, the incumbent, has staked his presidency on the ongoing negotiations with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), a left-wing group founded in 1964 out of the political turmoil that stretches back to the assassination of liberal presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948 and ‘La Violencia’ that followed for the next decade. Over the last half-century, FARC has been an impediment to a truly peaceful Colombia, even as the worst days of the drug-fueled violence of outfits like the Calí and Medellin carters have long receded.

His opponent, Óscar Iván Zuluaga (pictured above, right, with Santos, left), is the protégé of former Colombian president Álvaro Uribe, who broke with Santos over the FARC talks. Santos served as defense minister under Uribe, he won the presidency in 2010 with Uribe’s full support, and he had been expected to continue the same militaristic push against FARC that Uribe had deployed.

When FARC offered up the possibility of peace talks, Santos surprisingly met the offer, and official talks kicked off in October 2012. The talks were designed to reach agreement on five key points — agrarian land reform and agricultural development, political participation for former FARC militants, the mechanics of ceasefire and ending the conflict, staunching the drug trade and creating a truth commission and compensation for the victims of abuses at the hands of government-backed paramilitary groups.

Those talks have reached accords on three of the five areas, most recently on ending drug trafficking — more than two decades after the death of Pablo Escobar and the demise of Colombia’s major cartels, FARC has become a leading conduit for cocaine and other drugs from Colombia and elsewhere in South America northward.

Zuluaga hasn’t exactly said that he’ll end the talks if he’s elected president. But he has indicated he’ll impose conditions as president that FARC leaders seem unlikely to accept, all but ending the best chance in a half-century to negotiate a political solution to the leftist insurgency, which follows a relatively successful Uribe-Santos military effort that has significantly weakened, if not eliminated, FARC. Moreover, Colombians say in polls that they have no sympathy for FARC, and they generally support the talks, in principle at least.

So the election is truly momentous, and the result will almost certainly determine whether the FARC talks will continue.

* * * * *

RELATED: Zuluaga edges out Santos in first round

RELATED: Five reasons why Zuluaga is beating Santos

in Colombia’s election

* * * * *

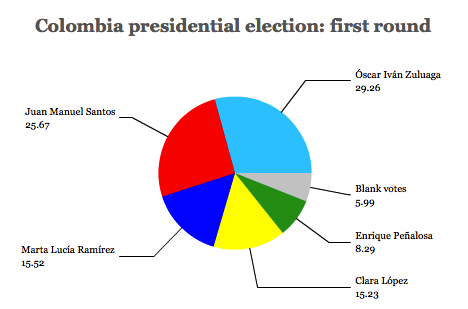

That’s not the reason, however, that Santos appears to be losing the election, after trailing Zuluaga in the first round on May 25.

Mary O’Grady, writing for The Wall Street Journal, serves up an analysis of the Colombian election that misses entirely the reason why Santos is in such trouble headed into the June 15 runoff:

A year ago Mr. Santos—part economic liberal, part old-fashioned populist—seemed certain to keep his job. Real gross domestic product expanded by an average annual 4.7% from 2010-13, and in 2011 Colombian debt won investment-grade status from all three major U.S. credit-rating firms.

Had Mr. Santos run on this record he might have won in the first round. Most voters don’t see much difference on economic policy between him and Mr. Zuluaga—the former CEO of a Colombian steel fabricator. But he made the FARC talks the centerpiece of his re-election campaign, which opened his weakest flank.

According to O’Grady (and, to be fair, other commentators), Santos would be winning this election if only he had merely rebuffed FARC’s negotiation entreaties. Most beguiling is the notion that Santos’s chief strength is Colombia’s economy.

It’s not. That’s actually the issue that’s most jeopardized his reelection. He could lose on June 15, not because of the FARC talks, but because he hasn’t offered any solutions to the everyday Colombians who feel like they have lost out in what otherwise looks like a stellar economy.

If Santos loses on Sunday, it will be less because he spent so much time negotiating with Iván Marquéz, the lead FARC negotiator, but because he didn’t take Cesar Pachón, a leading agrarian protester, seriously enough. Yes, Colombia is growing at around 5%, and by US or European standards, that qualifies as high growth. But when hasn’t Colombia’s economy grown? Call it realismo magico, but Colombia’s economy hasn’t faced a recession since 1999, and its economy’s retraction that year marks the only time since FARC’s inception that its economy hasn’t expanded. That dip in 1999 was the first Colombian recession in nearly 60 years, and it was one of two recession in the past century. That means that Colombia’s economy grew through World War II, through La Violencia in the 1950s, and even (mostly) through the entire period of political and social turmoil from the early 1980s to the early 2000s, when you could credibly characterize Colombia as a failed narcocracy.

Sure, it’s necessary that a Colombian leader must preside over stellar economic growth to win reelection, because that’s the standard to which Colombians have become acclimated for over a century. That doesn’t mean that everyday Colombians necessarily feel the benefits of economic growth. It means nothing to rural farmers that Colombia has now become Latin America’s third-largest economy, after Brazil and México, if the gains accrue to wealthy service providers in Bogotá and other urban centers. Colombia’s economy over the past four years has been great for mining and for services, but less so for agriculture and for manufacturing. That means that behind the headline economic data, many Colombians are actually struggling.

Somewhat improbably, Zuluaga has emerged as the more populist and even charismatic voice on economic policy. A technocratic former finance minister who is still viewed as Uribe’s presidential understudy, Zuluaga has nonetheless connected with more voters with his pledges to create jobs and increase social welfare spending, even though he largely agrees with Uribe over the character of Colombian economic policy. Both candidates support free trade, liberalization and other mainstream neoliberal policies.

While Zuluaga and Uribe, who won election to the Colombian Senado (Senate) earlier this spring, are running on a slogan of ‘mano firme, corazón grande,’ (strong hand, big heart), it might as well be ‘strong hand, open wallet.’ On the campaign trail, Zuluaga has repeatedly promised to deliver 6% growth, and he’s promised all sorts of economic goodies, including loan forgiveness for small farmers, and eliminating sales tax on agricultural equipment. Zuluaga has pledged to increase social welfare spending on health care, education and housing as well, financed in part by retaining an unpopular estate tax.

Though Santos wasn’t dumb enough to run on a slogan like ‘Colombia Shining,’ everything about his presidency and, now, his reelection campaign, suggests he has been far too complacent over those bread-and-butter issues upon which Zuluaga has made gains.

Rural farmers are a case in point — and that’s why Santos has spent so much of the runoff campaign apologizing to them for ignoring their concerns. Last August, he even refused to acknowledge that farmers were striking in the rural northeast of the country. Pachón has refused to endorse either Santos or Zuluaga, noting that both candidates essentially espouse neoliberal economic principles. But Zuluaga has been more successful winning support from other farmers’ groups in the last week, and Pachón had particularly harsh words about Santos’s indifference:

When asked about the two candidates’ initiative for the agricultural sector, Pachón expressed his disappointment with [Santos], saying that he did not try to get closer to the farmers during these elections and has constantly “underestimated” the farmers.

“President Santos didn’t want to meet with us. If he doesn’t talk to us now, how will he treat us in the following 4 years? (…) He underestimated us in the strikes, he doesn’t give us clear answers, he doesn’t give us resources for the farmers commuting from the north or south of the country. We can not even get in touch with the minister now, we are talking to the subordinates who have no power in decision-making.” said Pachón.

After the first round, I argued that a ‘peace front’ would form, with the various elements of Colombia’s political centrists and center-left and socialists all uniting behind Santos. Some Colombians privately predicted that the runoff would feel like France’s 2002 presidential election, in which the entire political mainstream lined up behind Jacques Chirac to oppose the xenophobic Jean-Marie Le Pen.

But that hasn’t happened, and it’s another piece of evidence that behind the headlines over FARC, the real catalyst for Zuluaga’s rise is economic conditions. Though Clara López, the candidate of the Polo Democrático Alternativo (Alternative Democratic Pole), has endorsed Santos, many of her followers haven’t followed suit. Former Bogotá mayor Enrique Peñalosa, who finished an incredibly poor fifth place, hasn’t endorsed anyone in the runoff. That suggests that the peace talks aren’t as important to most Colombians as traditional ideological differences over economic policy.

Santos has the support of several groups that once supported Uribe, including the Partido Liberal Colombiano (Colombian Liberal Party), the Partido Social de Unidad Nacional (Social Party of National Unity, ‘Party of the U’) and Cambio Radical (Radical Change).

Zuluaga has the support of Uribe’s newly formed party, Centro Democrático (Democratic Center) and, after the first round, the support of Marta Lucía Ramírez, the candidate of the Partido Conservador Colombiano (Colombian Conservative Party).

If Santos loses on Sunday, it will almost certainly doom the FARC talks. But if that happens, it won’t be solely, or even primarily because of Santos’s efforts to engage FARC. The negotiations, which represent Colombia’s best chance in a half-century to move beyond guerrillas and trafficking and toward a more normalized, peaceful existence, will fall victim to a Zuluaga victory. But correlation, in this case, doesn’t necessarily indicate causation.

Photo credit to Caracol TV / Diego Lurduy.

2 thoughts on “In Colombia’s election, it’s the economy (not FARC), stupid”