Though business tycoon and pro-Western opposition figure Petro Poroshenko easily won election as Ukraine’s next president in last Sunday’s election, the final numbers suggest that he’ll take the helm of a divided country.![]()

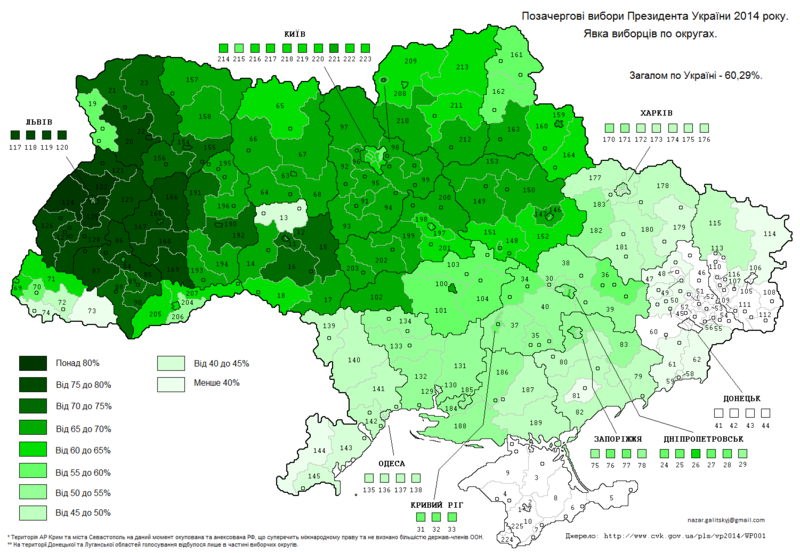

Here’s a map of turnout nation-wide:

What’s immediately apparent is that turnout was extremely low in the eastern oblasts that have been the scene of several pro-Russian separatist movements. Notably, many parts of Donetsk oblast didn’t even participate in the election.

Though Poroshenko won 54.70% of the vote, with other candidates barely winning more than single digits, he’ll be hard pressed to argue that he has a mandate from the eastern Ukrainians who now feel so alienated from Kiev’s central government and the rest of the country.

* * * * *

RELATED: In-depth: Ukraine’s elections

* * * * *

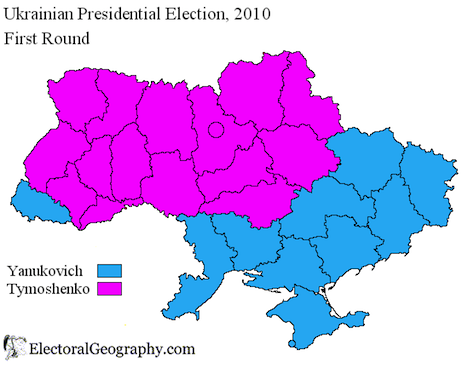

It’s a far cry from the 2004 and 2010 presidential elections, which saw voting highly polarized, also on west-east lines. But compare the map of turnout in the 2014 election to the following map showing the relative support of Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych in 2004 and the relative support of Yulia Tymoshenko and Yanukovych in 2010:

There’s an obvious link between the support for Yanukovych in 2004 and 2010 and regions with depressed turnout in 2014.

It’s same Ukrainian divide that’s only become more pronounced over the past decade. Accordingly, the lesson of the 2014 election isn’t so much that Poroshenko has magically and suddenly united Ukraine, it’s that eastern Ukrainians have been effectively disenfranchised.

Note, also, that Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March has removed another bloc of voters that, in 2004 and 2010, opposed Ukraine’s pro-Western presidential candidates.

Since the election, Poroshenko has indicated that he’ll take a hard line against eastern separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, and, if anything, fighting between Ukrainian forces and the separatists has escalated since May 25, with a particularly deadly clash over the Donetsk airport.

That’s not to say that Poroshenko hasn’t offered olive branches as well. Russian president Vladimir Putin has cautiously recognized the election result, and the Kremlin seems cautiously willing, for now, to work with Poroshenko. Though his current popularity stems from his role in the pro-Western Maidan Square protests, Poroshenko is something of a chameleon in Ukrainian politics, serving in the past five years both as foreign minister to the pro-Western Yushchenko and as international trade minister to the pro-Russian Yanukovych. He’s backtracked on calls for Ukraine to join NATO, and he’s indicated that, even as he hopes for closer economic integration between Ukraine and the European Union, he realizes that Ukraine and Russia must also have decent working relations.

Putin seems to be backtracking from the possibility of annexing eastern Ukraine, and even earlier this month, he appeared to back away from the separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk, urging them to delay planned referenda on independence from Kiev. (The referenda proceeded, though Kiev obviously didn’t recognize their legality or accept the results.)

But it’s worth noting the weighty inventory of expectations that await the Poroshenko administration:

With no serious contenders, and no real national debate during the election campaign, Poroshenko, who has dodged between both pro-Western and pro-Russian governments for the past two decades, and who has ties to some of the country’s most notoriously corrupt oligarchs, seems to be promising everything to everyone — and polls show he’s going to succeed. He pledges to restore ties with Russia, even while enhancing Ukraine’s economic links with Europe. He will somehow reverse what’s been a near-comical bungling effort by the Ukrainian military to subdue a separatist movement that shows no signs of receding. While doing all this, he will create jobs amid an economic crisis that will require more than $15 billion to $20 billion or more in financial assistance from groups like the International Monetary Fund, which will almost certainly demand in exchange tough budget cuts, tax restructuring, the privatization of many state-owned assets and the liberalization of Ukraine’s economy otherwise, steps that will almost certainly inhibit immediate economic growth that could bring about new jobs in the short-term. All of this in a country that, among the former Soviet nations, has the absolute worst post-Soviet GDP growth rate.

In short, Poroshenko is arguing that he can do what none of Ukraine’s leaders have been able to do for the past two decades at a time when the country is more divided than ever.

Commentators in the United States and Europe believe there’s cause for optimism, and that Poroshenko’s election victory can mark turning point in the Ukrainian crisis. Though there’s good reason to share that optimism, the path forward for Ukraine and for Poroshenko won’t be easy, and neither the gains from normalizing relations with both Russia and the European Union nor the gains from economic reform will be immediately apparent.