Though Iraqis voted on April 30, it took the better part of May for election officials to announce the results, which appear to be good news for Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki.![]()

![]()

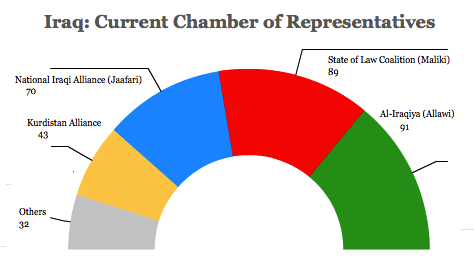

Heading into the elections, Maliki led a coalition of mostly Shiite parties, the State of Law Coalition (إئتلاف دولة القانون), dominated by Maliki’s own Islamic Dawa Party (حزب الدعوة الإسلامية). Maliki could rely on 89 seats in the 325-member Council of Representatives (مجلس النواب العراقي), Iraq’s unicameral legislature, but he governed as the head of a larger ‘national unity’ coalition after running on a broadly cross-sectarian, nationalist platform in the 2010 elections.

Iraqis, tired from the fierce Sunni-Shiite violence between 2006 and 2008, seemed weary of fighting, and the Iraqi political scene was then turning toward nationalism and away from sectarianism.

In those elections, Maliki’s State of Law coalition was actually bested by Ayad Allawi, a Shiite former prime minister who led a Sunni-dominated, cross-sectarian coalition, ‘al-Iraqiyya,‘ the Iraqi National Movement (الحركة الوطنية العراقية).

Allawi, however, wasn’t as successful as Maliki in building a governing coalition, so Maliki remained prime minister.

Here was the Chamber of Representatives on the eve of elections:

In the past four years, Iraq has witnessed a return to sectarian violence. After US forces left the country at the end of 2011, terminating a bloody eight-year military occupation, Iraqi security forces struggled to maintain the period of relative calm in which the 2010 elections took place.

Instead, by the beginning of 2014, Maliki was regrouping after radical Sunni militias had taken control of parts of western al-Anbar province, including its largest city, Fallujah. Militias are also taking advantage of the Syrian civil war to stir mischief on both sides of the Syrian-Iraqi border. The rise in Sunni-Shiite tension comes as relations between the northern Kurdish autonomous government and the central Iraqi government are also fraught over the issue of oil revenues.

* * * * *

RELATED: What is happening in Iraq, Fallujah and al-Anbar province?

* * * * *

Meanwhile, Iraq’s ‘national unity’ government has performed horribly. With corruption running rampant, and with minister more concerned with turf than performance, the country faces daunting problems — power outages, a weak non-oil economy, massive unemployment among a rapidly growing youth population, tax collection failure, among other problems.

So in 2014, Maliki ran a campaign designed to maximize votes within his own Shiite Iraqi community — and it’s a strategy that seems to have worked:

Maliki’s State of Law Coalition actually increased its share of the seats in the Chamber of Representatives from 89 to 92.

As Zaid al-Ali, a former legal adviser to the United Nations in Iraq writes in his excellent new book, The Struggle for Iraq’s Future: How Corruption, Incompetence and Sectarianism Have Undermined Democracy, the immediate results matter less than the fact that Iraq’s politics are stunted by elites who shuffle for power at the expense of governance:

Under the current constitutional and legal system, elections will not produce any real alternatives to Iraq’s ruling elite. The fortunes of some parties may rise, while others may see their popularity wane somewhat; but the chances of anything emerging outside the current crop of incompetent and corrupt politicians are vanishingly small…. In all likelihood, Iraqis will choose to stay away from the polls in increasing numbers, leaving the politicians to play an aggrandized version of musical chairs while everyone else just watches.

Maliki wins contest among Shiite Iraqis

Maliki’s focus on winning Shiite votes effectively turned the 2014 election into a contest among competing Shiite groups, most notably the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI, المجلس الأعلى الإسلامي العراقي), headed by Ammar al-Hakim, and the Sadrist Movement (التيار الصدري), headed by Muqtada al-Sadr, the former militia leader who returned to Iraq after four years of self-exile in Iran (and who, ostensibly, made a fuss earlier this year over his ‘retirement’ from Iraqi politics).

Middle Eastern experts believed that it was possible for the Sadrists and ISCI to win more seats, in aggregate, than the State of Law Coalition, thereby allowing Hakim to become Iraq’s next prime minister.

* * * * *

RELATED: Competing Shiite groups to determine Iraq’s next government

* * * * *

With 57 seats in total, the two groups will pose less of challenge to Maliki, who will now seek build a new coalition — either another national unity coalition or a majoritarian coalition. In either case, Maliki will almost certainly lead a government united not by an ideological agenda, but based upon dividing the perks of government.

There’s still a possibility that the anti-Maliki Shiite groups could form a government with the support of the Kurdish and Sunni blocs, but that seems unlikely, given Maliki’s strength.

Allawi, whose coalition crumbled over the course of the last four years, will now lead a bloc of just 21 seats under the banner of his longtime party, the Iraqi National Accord (الوفاق الوطني العراقي).

The view from Iraqi Kurdistan

The major Kurdish parties together won 62 seats. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP, پارتی دیموکراتی کوردستان), whose leader Masoud Barzani (pictured above), currently serves as the president of the Iraqi Kurdistan region, won 25 seats.

Its longtime rival, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK, یەکێتیی نیشتمانیی کوردستان), whose leader Jalal Talabani currently serves as the largely ceremonial president of Iraq, won 21 seats.

That’s a somewhat strong showing for the PUK, which suffered in last September’s Kurdish regional elections, not least because of Talabani’s health problems.

In last year’s regional elections, the newly formed Gorran (Movement for Change, بزوتنهوهی گۆڕان) emerged in second place. But Gorran won just nine seats in the national elections this spring, something of a setback for the promising Kurdish reform movement.

The results have cleared the way for a Kurdish regional coalition between the KDP and the PUK — regional leaders had been waiting for the national results in order to form the new regional government.

* * * * *

RELATED: Bordered by chaos, Iraqi Kurdistan holds elections in relative oasis of peace and democracy

* * * * *

Kurdish leaders are now pumping 100,000 barrels of oil a day directly to Turkey, angering Maliki and Iraq’s central government, which has tried to maintain national revenue-sharing for established oil reserves. Maliki earlier this year suspended the Kurdish allocation of the national budget, which amounts to 17% of total spending, and Kurdish politicians and entrepreneurs are working to develop more of the region’s oil wealth. Foreign investors are showing greater enthusiasm for development in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is largely stable. Though the Kurdish regional government isn’t immune to corruption, it’s generally far more effective than Iraq’s national government.

The Sunni challenge

Maliki faces an increasingly bitter fight in his third term with Iraq’s Sunni population, whose participation in the April national elections was limited. In some parts of the country, it was simply too dangerous to hold elections; in other parts of the country, Sunni Iraqis shunned a contest largely seen as dominated by Shiite politicians.

Sunni leaders, once prominent in the Maliki government, have been displaced by Shiite officials. Most notably, Maliki’s government forced order vice president Tariq al-Hashemi to flee Iraq after charging him with murder and sentencing him to death.

Despite the tumult in al-Anbar province, it will still send 15 legislators to the Iraqi parliament, many of whom are moderate Sunnis.

Maliki photo credit to Muhannad Fala’ah / Getty Images.

Barzani photo credit to Safin Hamed / Getty Images.