Whenever I go to México City, I marvel at the way its indigenous history integrates into the fabric of the city. Nahuatl words, like ‘Chapultepec,’ meaning grasshopper, and ‘Xochimilco,’ a neighborhood featuring a series of Aztec-created canals, pepper the geography of the city. Those are just two of hundreds of daily reminders rooting Latin America’s largest modern megapolis of 8.9 million in the language and traditions of its pre-Columbian past. It’s where the Virgin of Guadalupe, a young Nahuatl-speaking girl, apparently revealed herself to Juan Diego in 1531 as the Virgin Mary, instructing him to build a church, launching one of the most compelling hybrid religious followings in the New World. Even the inhabitants of the notorious Tepito barrio worship Santa Muerte on the first of November with bright flowers, cacophanous marimba and not a small amount of marijuana, in celebration of the magical chasm between what is, for many Tepito residents, a gritty life and an often grittier death.

It’s the way that México City blends the mysterious and the mundane, matches the sacred with the profane and so blends the line between the indigenous and conquistador that it’s hard to know who conquered what. For all of those reasons, I often think of it as the unofficial capital of realismo magico.

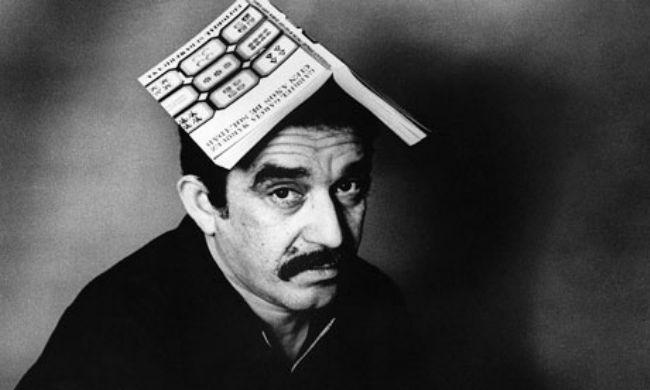

So it’s natural to me that the literary master of magical realism, Gabriel García Márquez, made his home in México City for much of the last six decades of his life. It’s also where García Márquez died on April 17 at age 87.

It was his uncanny ability to blend the realistic with the magical that largely won him such adoration worldwide. But what makes the writing of García Márquez and the other authors of the 1960s Latin American Boom so electrifying to me is the way that it blended the literary with the political. Certainly, García Márquez’s writing was about family, about love, about solitude, about power, about loss, about fragility, about all of these universal themes. But his writing also explicated many of the themes that we today associate with Latin America’s culture, identity, history and politics.

His death wasn’t entirely unexpected. García Márquez was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer all the way back in 1999 and by the beginning of the 2010s, he rarely made public appearances anymore due to the grim advance of Alzheimer’s disease. By the time I made it to Latin America for the first time, he was already approaching 80, and I knew I’d have little chance of meeting him.

That’s fine by me, because I always considered him, through his work, my own personal ambassador to Latin America. Over the course of several treks through Latin America, Gabo still accompanied me through his writing — and along the way, he shaped my own framework for how I think about Latin American life.

* * * * *

When I was planning my first trip to Latin America, I brought with me a copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude. I saved the novel for this very occasion, a trek from Buenos Aires to Mendoza and then by bus over the Andes to Santiago. Technically speaking, I was on the wrong end of the continent for García Márquez. I packed some Neruda, some Allende and some Borges — and some Cortázar, too (mea culpa, I still haven’t clawed enough time to read Hopscotch).

Nevertheless, García Márquez’s words transcended the setting of his native Colombia. Hundred Years, published in 1967, just six years after the Cuban revolution that undeniably marked a turning point in its relationship with the behemoth world power to the north, it came at a time when Latin American identity seemed limitless, and García Márquez mined a new consciousness that wasn’t necessarily Colombian or even South American. So much of the story of Colombia’s development from the colonial era through the present day is also cognizably Bolivian, Chilean, Mexican or Argentinian. After all, García Márquez, already a well-known figure, went on a writing strike when Augusto Pinochet took power in Chile in 1973, ousting the democratically elected Socialist president Salvador Allende, who either committed suicide or was shot on September 11, the day of the coup.

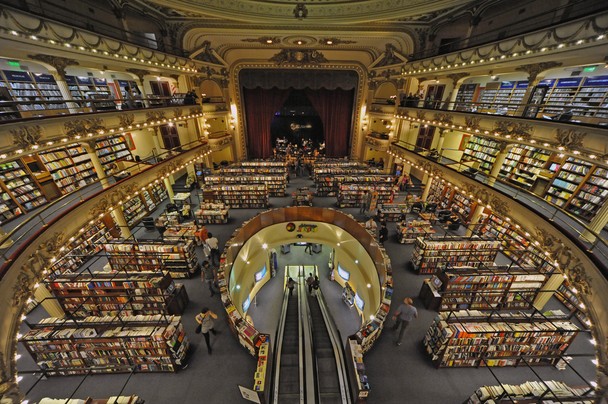

It was an intoxicating read. The sleek brown corduroy blazer I picked up in Buenos Aires with the affected hint of epaulets on the shoulders soon became what I called my ‘Colonel Aureliano’ jacket. Besides, where better to buy a Spanish language copy of his work than El Ateneo, perhaps the most amazing bookstore in the world?

* * * * *

Hundred Years, of course, came highly recommended from the world that had discovered García Márquez decades before I was even born. It became an instant hit upon publication, catapulting García Márquez’s popularity beyond his more established peers, including México’s Carlos Fuentes and Perú’s Mario Vargas Llosa.

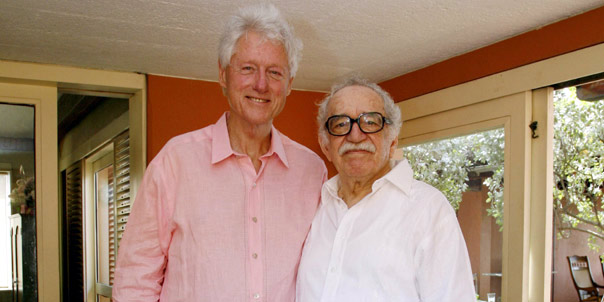

Bill Clinton, in his autobiography My Life, confesses to zoning out of class one day in law school to finish it:

Marvin Chirelstein taught me both Corporate Finance and Taxation. I was lousy at Taxation. The tax code was riddled with too many artificial distinctions I couldn’t care less about; they seemed to me to provide more opportunities for tax lawyers to reduce their clients’ obligation to help pay America’s way than to advance worthy social goals. Once, instead of paying attention to class, I read Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. At the end of the hour, professor Chirelstein asked me what as so much more interesting than his lecture. I held up the book and told him it was the greatest novel written in any language since William Faulkner died. I still think so.

Now, I’ll cop to having spent more than a few hours myself checked out of discussions on the Income Revenue Code’s Section 263 and the differences between business expenditures and capital expenditures. But it takes a lot of brass to pull out a book in the middle of class.

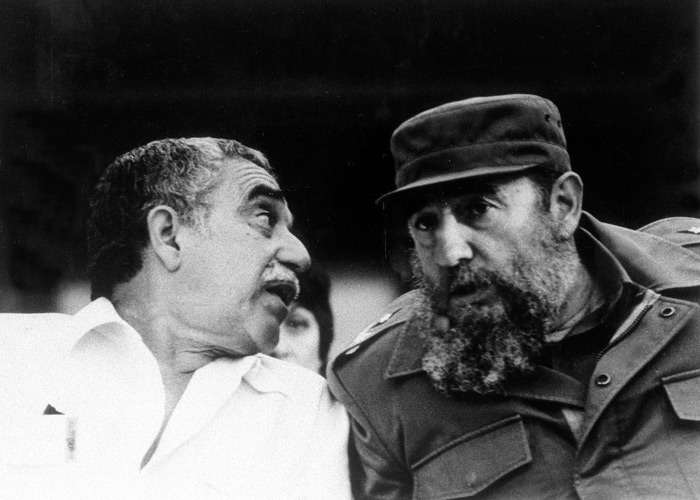

About 400 pages later in his autobiography, Clinton gets around to hobnobbing with García Márquez at Martha’s Vineyard (the two are pictured above in Cartagena last year). As Clinton notes and García Márquez often joked, the author might have been the only person in the world to count both an American president and Cuban president Fidel Castro among his close friends. When he first met Clinton in 1994, García Márquez tried to talk the young American president out of the longstanding US embargo against Cuba. Clinton joked that Castro already cost the US Democratic Party one election in 1980, and Clinton wasn’t about to let Castro lose another one. Though the Cuban embargo, celebrating its 54th year in 2014, is no joking matter, the anecdote explains how skillfully García Márquez graced the line between the world of letters and the world of politics.

He wrote his first article about Castro in 1958, a fawning piece based on an interview with Castro’s sister Emma, when they were both living in Caracas. That blossomed into an initially nervous meeting with Castro, though it was the beginning of a friendship that lasted a lifetime, even as García Márquez himself softened his own leftist views and came to embrace the reality of a market-driven world after the end of the Cold War.

But that friendship came at a cost. If there’s one attack that international critics have ably leveled against García Márquez, it’s that he was unwilling to criticize his powerful friends for their sins. García Márquez (pictured above with Castro) never acknowledged, for example, the political repression and economic stagnation the Castros have visited upon the Cuban people though illiberal authoritarianism and economic mismanagement. That’s not to say that the Cuban revolution didn’t bring about real achievements on some metrics. Just imagine, on an emotional level, what the Cuban revolution meant to a continent’s worth of humans suffering under the yoke of US-funded strongmen from Cuba’s Fulgencio Batista to Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza. No matter the initial glory of 1959, it’s still a disappointment, at least, that García Márquez was so silent in the face of his friend’s obvious shortcomings in 1969 and 1989 and 2009.

It wasn’t just Castro, though. García Márquez remained silent on the Tlatelolco massacre that so marred the 1968 México City Summer Olympics as well as the PRI’s decades-long grip on power in a country that he would ultimately come to spend more time in than his native Colombia. The attack’s mastermind was interior minister Luis Echeverría, and García Márquez visited him for an amiable chat months later, when he had become México’s president.

* * * * *

In nearly two weeks in Peru, I may have been the first US traveller to skip Machu Picchu in favor of Lima’s cold, desert cityscape, the magnificent, sunbaked ruins of Chan Chan, and the northern highlands of Cajamarca. García Márquez joined me again, this time speeding along in a bus from Trujillo up to the Andes, offering up Love in the Time of Cholera (and with three separate bouts of food poisoning throughout the trip, I thought I might have contracted cholera). For me, the most enduring vision of the novel comes at its beginning, the necessary moment that propels the eventual love story — when the elderly doctor, Juvenal Urbino, climbs a ladder to catch a parrot, in child-like wonder, only to slip and fall to his death moments later. It’s a macabre, Hitchcockesque sort of trick. When I moved on to Vargas Llosa’s Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter a few days later, I imagined its protagonist Pedro Camacho as a kind of bizarro version of the young García Márquez working as a writer in Bogotá, Europe, New York and México City in the days before achieving fame.

Vargas Llosa, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010 (only 28 years after García Márquez), was already emerging as the dean of the mid-century Latin American literary set when García Márquez arrived on the scene and quickly overshadowed him and everyone else. Nonetheless, both writers powered Latin American literature to a global audience, and for a long time, the two were intimately close. García Márquez served as godfather to Vargas Llosa’s second son, and Vargas Llosa wrote a book about his friend and his work.

But one of the enduring mysteries of García Márquez lore comes from the legendary break between the two friends in 1976 at a film premier in México City. As Gerald Martin writes in his biography, Gabriel García Márquez: A Life:

…Vargas Losa, in town for the event — he had written the screenplay — was standing in the foyer. Gabo opened his arms and exclaimed, ‘Brother!’ Without a word Mario, an accomplished amateur boxer, floored him with one might blow to the face. With García Márquez semi-conscious on the ground, having struck him head as he fell, Mario then shouted, depending on the source: ‘That’s for what you said to [Vargas Llosa’s wife] Patricia.’ Or: ‘That’s for what you did to Patricia.’ This was to become the most famous punch in the history of Latin America, still the subject of avid speculation to this day. There were many eyewitnesses and there are many versions not only of what actually happened but why.

It is said that the Vargas Llosa marriage went through a difficult moment in the mid-1970s and that García Márquez took it upon himself to console Mario’s apparently distraught and resentful spouse. Some say that he did this by advising her to initiate divorce proceedings; others say the comfort he offered was more straightforward. Evidently Mario concluded that García Márquez had put his concern for Patricia before their friendship. Only García Márquez and Patricia Llosa know what did or did not happen.

From a literary standpoint, their friendly rivalry always loomed under the surface. Given García Márquez’s leftist politics, however, the two might have had reason to come to blows regardless of their personal differences. Vargas Llosa ran for the Peruvian presidency in 1990 on a campaign of center-right, neoliberal reform, including massive privatizations. That approach to economics may now be orthodox for both the Peruvian right and the left, but Vargas Llosa’s campaign was a disaster, evidence of why literary figures may make fine revolutionaries but rarely fine politicians or public officials. What’s more, Vargas Llosa’s failure loosed the corrupt, authoritarian strongman Alberto Fujimori upon the Peruvian people for the next decade. At the time, García Márquez offered qualified praise, wishing Vargas Llosa success. But I’ve often wondered what García Márquez must have felt about his one-time friend and mentor’s foray into Latin American politics.

* * * * *

On my first trip to Colombia a few years later, I found in Martin’s biography an indispensable guide, not only to the life of García Márquez (who joked that every self-respecting author should have an English biographer), but also to Colombian history and politics. When I joined a friend in the summer of 2010 for a getaway to Cartagena, I hijacked the junket into a veritable field trip of GGM adoration.

Though Anand Giridharadas may have proclaimed Cartagena as ‘Latin America’s hippest secret’ in an otherwise wonderful 2010 piece from The New York Times that became our GGM syllabus for the week, it was a secret that had loosed itself to far too many travelers by the time we arrived — at least, from the looks of the dozens of emeraldmongers clogging up the paths of the central Plaza Bolívar. Undaunted, we explored the ins and outs of the coast and some of the surrounding Islas de Rosario. After a white-knuckled ride on a motorboat across the open ocean, I cracked open a collection of Gabo’s short stories in hand for beachside reading:

“All of my books have loose threads of Cartagena in them,” Mr. García Márquez said in the documentary. “And, with time, when I have to call up memories, I always bring back an incident from Cartagena, a place in Cartagena, a character in Cartagena.”

Back in Cartagena, we traipsed through Plaza Fernández de Madrid, the setting for Love in the Time of Cholera. It’s also where, unable to resist a fruit juice made from zapote, a fleshly brown fruit with an odd taste often likened to chocolate, I likely contracted the protozoan guest who stayed with me for a couple of weeks after I returned to the United States. No matter, I don’t regret downing my first icy zapote juice under the kind of equatorial midday sun that hangs directly overhead.

We sought out the sleek, modern home (pictured above) that García Márquez keeps for his visits back to the Colombian coast, and we sipped cocktails at the Sofitel Santa Clara, which was once a convent and a hospital.

When I visited Bogotá with another friend for the first time a few years later, I understood what García Márquez meant when he felt it was another country. As Martin writes about the author’s first trip to Bogotá at the age of 16:

The train arrived in the capital at four o’clock in the afternoon. García Márquez has often said it was the worst moment of his life. He was from the world of sun, sea, tropical exuberance and prejudices. On the Sabana everyone was wrapped up tight in a ruana or Colombian poncho; and in rainy and grey Bogotá, backed up against the Andean mountains at a height of 8,660 feet, it seemed even colder than on the Sabana; and the streets were full of men in dark suits, waistcoats and overcoats, like Englishmen in the City of London; and there were no women anywhere to be seen.

Nonetheless, though our time in Bogotá was often rainy and cloudy, it wasn’t nearly as dreary as you might expect, and on our way up the Cerro de Monserrate for lunch and a view of Bogotá from above, we found some hummingbirds that wouldn’t seem incredibly out of place in any of García Márquez‘s work:

If the greatest criticism abroad of García Márquez is his uncritical friendship with the Castros, perhaps the greatest criticism back home, however gentle, is that he abandoned Colombia as it fell apart in the mid-1980s. Despite the increasing and unmistakable evidence of human rights abuses committed by the Colombian military during the presidency of Conservative Belisario Betancur, García Márquez waited until the last week of Betancur’s presidency to warn that the country was on the brink of a ‘holocaust.’

Time and time again, he delayed and cancelled plans to return to Colombia, even to his beloved Costa. By the early 1990s, when Liberal president César Gaviria took power, the initially skeptical García Márquez endorsed Gaviria’s hard line against the Colombian guerrillas with increasing vigor. The two eventually became close friends over the course of Gaviria’s presidency, during which US and Colombian forces finally tracked down and killed Pablo Escobar, the infamous head of the Medellín cartel.

If the Gaviria administration marked the final rift between García Márquez and the far left in Colombia, it also coincided with an increasingly moderate political worldview. In 1991, for example, he traveled to the United States for the first time in three decades — he had been denied a visa for the past 30 years due to his socialist sympathies.

* * * * *

That doesn’t mean García Márquez abandoned Castro in the 1990s or later in his life, but it does mean that he cast a more skeptical eye to some of Latin America’s 21st century socialists. Naturally, Gabo took great interest in Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, who attempted to take power in a 1992 coup and ultimately won it through democratic means in the 1998 election. In so doing, he swept aside two rotten, rudderless parties with their own respective oil-fueled patronage networks. Chávez, by means of a new constitution, would ultimately flatten not only the oil patronage system but state, party and oil company under the mantle of chavismo, a system that today, 13 months after his death, appears to be crumbling into the biggest economic and political crisis since the 1989 Caracazo riots.

In one of the more prescient analytical pieces profiling Chávez shortly before he took office in 1999, García Márquez nailed the late Venezuelan as well as just about anyone — and certainly not in sycophantic tones:

President Hugo Chávez told me this story on the Venezuelan Air Force plane which took us from Havana to Caracas, less than 15 days after he took office as the constitutional president of Venezuela, elected by popular vote. We had met for the first time three days before in Havana, during his talks with Presidents Castro and [Colombian president Andrés] Pastrana. The first thing that struck me was the power of his cement-reinforced body. He had an easy cordiality and the native grace of a pure blooded Venezuelan. We both tried to see each other again but for both of our faults it wasn’t possible, and so we went together on the plane to Caracas to talk about his life and its miracles. It was a good experience for an otherwise unoccupied reporter. As he recounted his life, I was discovering a personality which had absolutely no relation to the idea of a despot we had formed from the news media. It was another Chávez. Which of the two was the real one?….

The plane landed in Caracas at three in the morning. I saw through the window the mist of lights of that unforgettable city where I lived for three years, as crucial for Venezuela as they were for my life. The President took his leave with a Caribbean embrace and an implicit invitation: “We’ll see each other here February 2nd.” While he moved off among his military escort and old friends, I shuddered at the thrill of having gladly traveled and talked with two contrary men. One to whom inveterate luck has offered the opportunity to save his country. And the other, a conjurer who could go down in history as one more despot.

When I flew into Caracas fourteen years later, Chávez had been dead for a month, and Venezuela was preparing to vote for the first time since that 1999 Havana-Caracas flight that wouldn’t feature Chávez on the ballot, either directly or indirectly. With his hand-picked successor Nicolás Maduro claiming that Chávez was resurrected as a bird to whisper encouraging words to Maduro in his presidential campaign, the old comandante‘s ghost haunted the entire affair. The inherent unfairness of the chavista system delivered a victory for Maduro over challenger Henrique Capriles, though it was much narrowed than anyone expected and remains widely disputed today.

Chávez came to resemble the protagonist of one of García Márquez’s least successful novels, The General in His Labyrinth, a fictionalized account of the later years of Simón Bolívar, the great liberator of Venezuela, Colombia and much of the northern part of South America from Spanish colonial rule in the 1820s. Gabo’s dear friend Castro cryptically noted its ‘pagan image’ of Bolívar. The book, based on historical research of Bolívar’s final years, traces the loneliness and death of one of Latin America’s first powerful figures, a subject that must increasingly cross the retired Castro’s mind — he, too, is 87 years old.

Chávez, throughout his 13-year reign, redefined Bolívar in his own socialist agenda. A great Bolivarian revolution! He even created a new, modernist mausoleum (pictured above) to house the remains of the liberator. When I went to visit, however, on an otherwise sunny tropical morning, it was locked. The guards told me it was closed for ‘renovations’ for the next few weeks.

It was an obvious choice that I should add General to my stack of books about Venezuela to devour before leaving for Caracas.

Again, García Márquez fused the literary and the political/historical, and though he couldn’t have imagined Chávez when he was writing the book in the late 1980s, it’s hard not to find the same themes of isolation, paranoia and destiny in Chávez’s own opera-worthy rise to power — and the talented grip with which Chávez not only held onto power but submerged every state institution into the greater cause of his Bolivarian revolution.

* * * * *

We will never read what García Márquez thinks about México’s still-newish president Enrique Peña Nieto, or the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro or whatever happens next in Venezuela. But maybe that’s as it should be. The issues facing Latin America today, though they are important, just don’t register on the same scale as in García Márquez’s heyday. The Cold War is over, most of Latin American’s dictators have long ago died (or are facing criminal charges for genocide and other crimes), the US-catalyzed Central American civil wars of the 1980s are fading from memory, and everyone from Colorado to Uruguay is slowly abandoning the insanity of US drug-war policy. From Brazil to Honduras, it’s a time of progress for human rights, women’s rights, LGBT rights, environmental rights, indigenous rights, and so on.

Both the early promise of the Cuban revolution and the cruel reality of Cuban socialism have given way to a gerontocracy that might have worked itself into oblivion decades ago if not for the anti-imperialist mantle that both Republicans and Democrats in the United States have gifted the Castros for ten consecutive administrations. Even in García Márquez’s home country, the narco-trafficking that reduced Colombia to a failed state between the 1980s and the 1990s is a memory, and the government of president Juan Manuel Santos is working feverishly to conclude a peace with the FARC, ending a 50-year guerrilla insurgency. Military helicopters are less important in Bogotá today than bike lanes, and a new green, liberal middle-class politics is emerging. The biggest threat to Santos’s reelection this summer isn’t the old-school national conservative hierarchy, it’s the Green Party’s business-friendly candidate, Enrique Peñalosa, himself a former Bogotá mayor. After the Cuban missile crisis or the Pinochet regime, it’s hard to get so worked up over Mexican energy reforms or Chilean education policy.

With a few notable exceptions, Latin American politics today are fairly boring.

That’s basically great news for Latin America’s emerging economic and political stability. But for the sake of world literature and world politics, we should be thankful that we had García Márquez exactly when we did.

El Ateneo photo credit to Vivien Leung.

Clinton/GGM photo credit to Yomaira Grandett / El Tiempo.

This is a really good tip especially to those fresh to the

blogosphere. Brief but very precise info… Appreciate your sharing

this one. A must read post!