For the second time in as many months, Ukraine’s crisis threatens to spiral out of control, with the Ukrainian military now trying (mostly in vain) to secure several cities in the Russian-speaking east from a band of pro-Russian separatists. ![]()

![]()

Just over a month ago, Russia annexed Crimea, the peninsula region in the south of Ukraine with an overwhelmingly large Russian ethnic population. For all the bluster between Washington and Moscow, you’d have thought that Crimea was as important to the international world order in 2014 as Cuba was in 1963 or Hungary was in 1956.

But the world largely seemed to accept Russia’s annexation of a region that was, after all, part of Russia until 1954. Yesterday in Geneva, after as the United States, Russia, Ukraine and the European Union reached a somewhat thin agreement to reduce the current tension in eastern Ukraine, US secretary of state John Kerry tersely declared, ‘we didn’t come here to talk about Crimea.’

So what’s so different now? Will the latest framework, agreed just on Thursday, succeed? Was Crimea just a warmup act for a larger Russian annexation?

* * * * *

RELATED: Why more protests won’t solve Ukraine’s political crisis — and why the Orange Revolution didn’t either

RELATED: What comes next for Ukraine following Yanukovych’s ouster

* * * * *

Not to worry. Here’s everything (and more) you probably ever wanted to know about the Donbass, the eastern-most region of Ukraine that’s now center-stage in the latest round of the fake Cold War.

What is the Donbass?

The Donbass — or the Donbas (It’s Донбас in Ukrainian, Донбасс in Russian, and if we’ve learned anything about linguocultural conflict, it that language matters a lot) gets its name from the Donets Basin, which is the coal-mining, heavy-industry heart of eastern Ukraine. As a formal matter, the Donbass includes just the northern and center of Donetsk oblast (an oblast is Ukraine’s version of a state), the south of Luhansk oblast, and a very small eastern part of Dnipropetrovsk oblast.

It’s been a coal-mining region since the 1870s, and during the Soviet era, it became Ukraine’s industrial and heavy industry heartland, emerging with a strong metallurgy as well as mining sector.

Despite a strong Russian minority, it’s perhaps more accurate to describe the Donbass region as more ‘Soviet’ than ‘Russian.’ As Ararat L. Osipian and Alexandr L. Osipian wrote in a paper for Demokratizatsiya, Why Donbass Votes for Yanukovych: Confronting the Ukrainian Orange Revolution, the Donbass has a particularly strong regional character, and Donbass pride is less about Russia or Ukraine than about Donbass itself. It was just as fiercely independent when it was part of the Soviet Union.

There’s a minor history of independence throughout the region — the Donetsk-Krivorozsk Republic came into quasi-existence for about a month in 1918. The aim was to separate from the rest of Ukraine, and it was the pet project of Bolshevik leader Artem Sergeyev, who became to the Donbass region what Vladimir Lenin was to the rest of the Soviet Union. While the city of Donetsk became ‘Stalino’ for a brief period in the mid-20th century, Donetsk’s main street, even today, is still called Artema Street.

This Donetsk oblast seems to be fairly important? Tell me more.

Donetsk oblast, historically, forms the heart of the Donbass region and, accordingly, it’s a central focus of the current standoff between regional separatists and Ukraine’s interim government. Its capital, Donetsk, is the largest city in the Donbass region. Though ethnic Russians don’t comprise a majority here, they do comprise a sizable and significant minority.

Donetsk is the most populous oblast in Ukraine with 4.38 million people, and its also one of the densest parts of the country.

Believe it or not, Donetsk was founded in 1869 by John Hughes, a Welsh businessman, who wanted to develop eastern Ukraine’s industry, and it was initially called Hugheskova. Until the tumult of the Russian revolution, it had a sizable Anglo population and, until it was flattened by German bombers in World War II, had a recognizably Anglo layout and architecture.

As it turns out, Donetsk oblast has one of the strongest economies in Ukraine. That’s not saying much, because Ukraine has struggled mightily for the past two decades. But while Donetsk is by no means wealthy, its per-capita GSP (as of 2011) was around $4,600, significantly higher than the average Ukrainian GDP of around $3,600.

So you can see why Ukraine’s interim president Oleksandr Turchynov is anxious to keep Donetsk and the Donbass from spiraling out of control.

Does the Donbass accept the current Ukrainian government?

Turchynov is a native of Dnipropetrovsk in eastern Ukraine just west of the Donbass, and he worked early in his career for former president Leonid Kuchma, who governed largely with the east’s support. But Turchynov also served as deputy prime minister from 2007 to 2010 under Yulia Tymoshenko, so he’s largely aligned with Ukraine’s western, pro-European political forces. What’s more, interim prime minister Aresniy Yatsenyuk is even more pro-Western, he leads the party that Tymoshenko founded — ‘All Ukrainian Union—Fatherland’ (Всеукраїнське об’єднання “Батьківщина) — and was one of the major political figures working to oust former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych.

Though the current interim government seems relatively in charge of the country’s institutions in Kiev and western Ukraine, the situation is dicier in the east. Even eastern Ukrainians were appalled by the brutality that Yanukovych deployed against protestors in his final days in office, but the region never had much use for the Euromaidan protests in Kiev. It didn’t have much use for the Orange Revolution or the pro-European presidency of Viktor Yushchenko back in 2005, either.

Eastern separatists argue that the current interim government is illegal — after all, Yanukovych was elected in a legitimate election four years ago. No one elected Turchynov and Yatsenyuk, especially not the Donbass.

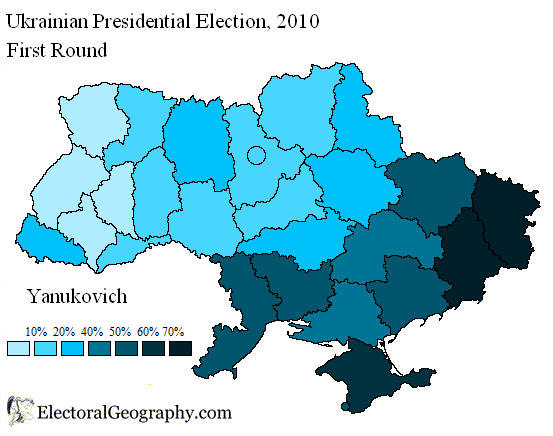

For the past decade, the Donbass overwhelmingly supported Yanukovych, a Donetsk native, in national politics.

Check out the map of results from the 2010 presidential election. The two darkest blue, pro-Yanukovych oblasts in that election were Donetsk (where 76% of the electorate supported Yanukovych) and Luhansk (71.1% supported Yanukovych).

With the near collapse of Yanukovych’s eastern-based Party of Regions (Партія регіонів), and with businessman Petro Poroshenko leading polls to win Ukraine’s planned May 25 presidential election, the region could find itself increasingly isolated. Even as the rest of the country embraces Poroshenko, the Donbass may rally instead around Donetsk native Petro Symonenko, the leader of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Комуністична партія України).

The potential political isolation of the Donbass region represents one of the most difficult challenges for the winner of next month’s election.

Who are the separatists in Donbass and how much support do they have?

That’s a very good question — and no one really knows the answer for sure.

That’s because no one knows exactly who the separatists are. Though there are pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine, they were always a very small minority until recently — just as in Crimea, where the current pro-Russian prime minister won about 4% in the last regional elections.

In eastern Ukraine, a shady figure named Denis Pushilin has proclaimed himself the spokesperson for the newly declared People’s Republic of Donetsk. Though his group has occupied several government buildings in Donetsk, no one’s taking the independence declaration incredibly seriously. While the population of eastern Ukraine might not be incredibly enthusiastic about the current interim government, there’s no incredible groundswell of support for Russian annexation, either.

Western intelligence reports and other sources believe that, if the separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk aren’t actually covert Russian forces, they are almost certainly working in tandem with Moscow, or are at least being bankrolled by Moscow.

How are these regions different from Crimea?

Like Crimea, the Donbass has a distinct regional identity. But whereas Crimea has an ethnic Russian majority (around 58.5%), Donetsk oblast has an ethnic Ukrainian majority (around 56.9%), with a sizable ethnic Russian minority (around 38.2%). Luhansk has a similar demographic profile — around 58% ethnic Ukrainian and 39% Russian. But throughout the region, both ethnic Ukrainians and ethnic Russians tend to speak Russian as a first language, not Ukrainian.

But you could also say that of Kiev, Ukraine’s capital, where it’s often said that the people ‘speak Russian and think Ukrainian’ because while Russian is more predominant in Kiev than Ukrainian, its voters typically back western Ukrainian, pro-European leaders.

* * * * *

RELATED: Crimea prepares to vote in status referendum

RELATED: Let Russia take Crimea — the focus should be on Ukraine’s economy

* * * * *

In Donetsk, the largest city in the region, though, it’s a lot more balance — around 48% of the municipal population is Russian and around 46% of the population is Ukrainian. That’s still not as ‘Russian’ as Crimea, but it’s still close enough to worry.

Donetsk, and the Donbass generally, clearly falls under the gathering ‘Putin doctrine,’ whereby Russia will more aggressively looks out for the interests of ethnic Russians and Russian speakers outside the borders of today’s Russia.

Economically speaking, eastern Ukraine is also much stronger than Crimea, which still depends on the Ukrainian mainland for water, electricity and other goods. Despite its reputation as a resort town on the Black Sea, Crimea’s regional per-capita GSP is just around $2,450, much less than the Ukrainian average of around $3,600.

So would the Donbass be better off economically under Russian rule?

You’d imagine that if Russia tried to annex eastern Ukraine, it would work strongly to win over the hearts and minds of its newest Russian subjects with a lot of subsidies. In the long run, though, probably not.

As Osipian and Osipian write:

Donbass’s leaders clearly understand that they are more influential in Ukraine than in Russia. Moreover, Donbass’s mining industry receives subsidies from Kyiv. For some parts of Ukraine, it is more economically rational to import coal from Poland and Russia than to buy it from Donbass, but the government continues to subsidize some ineffective mines to avoid social problems. Hypothetically, if Donbass united with Russia, a number of Donbass’s mines would be closed and its metal plants would face rough competition from their powerful Russian counterparts. In these circumstances, owners of the metal industry and Yanukovych’s supporters would not have the protection and support of the government they enjoy now.

That seems clear enough.

But one of the complaints you hear from Donetsk is that the region contributes more to Ukraine than it receives in return from the national government. That’s a misconception — Donetsk actually receives more from Kiev, all things considered, than it contributes. If it weren’t true before Yanukovych’s ouster, it will certainly be true while the next government tries to build unity throughout Ukraine. But the region’s politicians, not least of which Yanukovych himself, were always happy to stoke up regional solidarity by emphasizing the widely held misconception.

Much of the Donbass’s antipathy toward Kiev isn’t necessarily Russian pride, it’s the kind of regional grumbling that you find in the United States against the pernicious influence of ‘Washington,’ for example:

Kyiv is the center of bureaucracy where one must go to settle different issues, resolve problems, and request money from the central budget…. They also believe that Kyiv is responsible for the arrears in wages, social transfers, and other payments from the central budget to the region. All of these characteristics help form a negative image of Kyiv.

On the other hand, people from Donbass go to Moscow for shopping and higher paying jobs. In contrast to Kyiv, Moscow is a major producer of TV programs, shows, books, and newspapers, i.e., popular culture….This contributes to the positive image of Moscow in Donbass. Donbass often underlines its independence from Kyiv in its relations with Moscow.

Which is to say, Donbass finds Moscow a useful foil off of which to play the central government in Kiev — that doesn’t mean eastern Ukraine is itching for secession and annexation into the Russian Federation.

I don’t care about the Donbass regional economy — why has this now become such a powder keg?

Ukraine is walking an incredibly tight line. If it pushes too hard, it could play right into Moscow’s narrative and it could legitimize a separatist movement that still’s only a fringe group. If it doesn’t push hard enough, it invites the separatists and Moscow to take a more aggressive posture.

Turchynov’s decision to send national Ukrainian troops to the east on Tuesday to retake key government buildings in an ‘antiterrorist campaign’ is fraught with anxiety. If the interim government doesn’t act to assert its control over eastern Ukraine, it risks looking weak and illegitimate. That’s exactly what happened earlier this week when Ukraine’s 25th airborne surrendered to a crowd of Ukrainian civilians.

Turchynov chastised the unit’s decision, though it’s not clear that he disapproved of the decision behind the scenes. That’s because the Ukrainian army must be very careful not to antagonize eastern Ukraine’s residents, even as the try to retake government buildings from the separatists. Right now, the Donbass population seems apathetic about both the separatists and the Kiev regime. A few casualties at the hands of an inexperienced army, however, could translate into real support for the separatists.

There’s not a lot of morale these days within the Ukrainian forces, either, who aren’t enthusiastic about fighting a civil war. Moreover, after the punishment meted out to forces that obeyed Yanukovych’s orders to fire on Ukrainians protesters in February, why should the military now obey Turchynov’s orders to fire on eastern Ukrainians?

The interim government must also be mindful of the Russians. If the Ukrainian forces don’t tread carefully, it won’t be hard for Russian president Vladimir Putin to use the tumult as an excuse to ‘come to the rescue’ of eastern Ukraine’s Russian population, thereby gobbling up even more Ukrainian territory. That’s what happened in Georgia in 2008 after president Mikheil Saakashvili ordered Georgian troops into the breakaway republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Six years later, both regions remain under de facto Russian occupation.

All of which explains why, so far, Ukraine has managed only to take back a small air force base in Kramatorsk and why it keeps backing away from ultimatums to the separatists.

So does that mean Putin is going to annex the Donbass?

No one really knows the answer to that question, but Putin is doing everything you might expect him to do to facilitate the occupation of eastern Ukraine.

Everyone, even the supposed liberals of the Russian government, including Russian prime minister Dmitry Medvedev (pictured above), are coordinating their line that Ukraine is on the ‘brink of civil war.’ If you’re looking for hints from Putin himself, he referred yesterday to Ukraine as Novorossiya, or ‘new Russia’:

Mr. Putin, appearing cool and confident during a four-hour question-and-answer show, referred repeatedly to southeast Ukraine as “New Russia” — a historical term for the area north of the Black Sea that the Russian Empire conquered in the 1700s. And, he said, only “God knows” why the region became part of Ukraine in the 1920s, signaling that he would gladly correct that error.

Around 40,000 Russian military forces are camped along the eastern border, and it wouldn’t take much for Putin to give the order to send his forces into Ukraine. Initially, at least, Ukraine’s army would be no match for the superior Russian military. In the long run, though, it could prove a costly venture for Russia, even in the best-case scenario. If Ukraine mounts a counterattack, it could do so with covert or open support from Washington, Brussels, Berlin and all of its NATO allies. Given Putin’s provocation, first on Crimea, and now on eastern Ukraine, it would be hard for Western leaders to ignore the calls to respond more forcefully. That means that the worst-case scenario isn’t just a Ukrainian civil war, but a proxy battle between Washington and Moscow, which is why the world’s powers are gathered in Geneva to resolve the crisis.

But outright annexation isn’t the only potential objective for Putin. If he’s looking to distract the interim Ukrainian government from the increasingly grave economic problems it faces, he’s certainly doing a very good job of it. Encouraging the pro-Russian separatists and baiting Kiev into sending troops into the region could also foment stronger anti-Kiev (and pro-Russian) sentiment as Ukraine prepares for both presidential and parliamentary elections later this year — elections that now favor the pro-European westerners, especially now that the Russian-majority Crimea is no longer part of Ukraine.

Will the Geneva agreement actually work?

The last agreement that Russia and the European Union concluded back in February meant to reconcile the demands of the Euromaidan protesters with the stability of the Yanukovych regime. Hours later, Yanukovych fled Kiev. So the track record isn’t incredibly strong.

Even as the Geneva compromise was announced, Putin was waxing about Ukraine-as-Novorossiya, and US president Barack Obama publicly doubted the agreement’s efficacy almost immediately, somewhat undermining Kerry’s efforts:

But President Obama sounded a cautious if not skeptical note in Washington. “I don’t think we can be sure of anything at this point,” he said, but there is a chance “that diplomacy may de-escalate the situation.”

The agreement is also incredibly vague. The joint statement declares that all illegal armed groups must be disbanded, all illegally seized buildings must be returned to legitimate owners, and all illegally occupied streets, squares and other public places in Ukrainian cities and towns must be vacated.

That could mean different things to each of the parties.

For Ukraine’s interim government, the Geneva deal obviously regards the separatist protests in eastern Ukraine.

But Russians may demand the disarmament of uncomfortably far-right groups like Right Sector (Пра́вий се́ктор), which played a role in the anti-Yanukovych protests and now play a role within the interim government. Dmytro Yarosh, Right Sector’s leader, is now the deputy director of Ukraine’s security council, for example.

Even if all the parties agreed on the terms of the Geneva framework, who exactly would do the disbanding, returning and vacating? The interim Ukrainian government’s performance so far doesn’t lend a lot of credibility that it’s up to the challenge.

Back in Donetsk, Pushilin rejected the Geneva agreement outright, highlighting that back in the Donbass, the issue is about the current interim government’s legitimacy:

Russia “did not sign anything for us,” Mr. Pushilin said at a news conference in Donetsk…. Mr. Pushilin said he did not consider the new government in Kiev to be legitimate, and that if illegally occupied buildings are to be relinquished, then its officials, including the president, Oleksandr V. Turchynov, should vacate the presidential administration building in the capital.

Top photo credit to Dimitar Dilkoff/AFP/Getty — a pro-Ukraine rally in Lugansk on April 15.

Donetsk photo credit to Anatoliy Stepanovanatoliy Stepanov/AFP/Getty Images.

Medvedev photo credit to Alexander Astafiev RIA Novosti/AFP.

Thanks for this article. I wanted to know about the Donbass and now I know, together with useful background information about the regions of Ukraine and why it’s a potential tinderbox.