On Wednesday, a bomb exploded outside the Bank of Greece.![]()

Though it injured no one, it was a stark reminder that, despite today’s apparently successful bond sale, Greece is pretty fucking far from okay, to steal a phrase from Pulp Fiction.

Astonishing just about everyone, Greece held its first bond sale for the first time in four years, raising €3 billion ($4.2 billion) at a freakishly low yield of 4.95% for a five-year issue. But demand for the bonds was more in the range of €20 billion ($27.8 billion), which is over 10% of current Greek GDP:

The order book includes €1.3bn of orders from the arranging banks, but is a striking confirmation of the ravenous appetite for eurozone periphery debt. One person close to the deal said there had been more than 550 different investor accounts placing orders.

€3 billion is not a lot of financing compared to the €240 billion that Greece has received through two bailouts funded by the ‘troika’ of the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission and the European Central Bank. For Greek prime minister Antonis Samaras and his coalition government, the sale was more a symbolic success than anything else — it’s a signal that Greece is once again open for business in the international bond market and emerging from the worst of its debt crisis:

“The international markets have expressed in the clearest possible manner their trust in the Greek economy, their trust in Greece’s future,” he said. “They have shown trust in the country’s ability to exit the crisis, and sooner than many had expected.”….

Deputy Prime Minister Evangelos Venizelos also hailed the country’s return to the markets, arguing that it was a “major achievement that Greece did not turn into Argentina or Venezuela.” He also launched a strongly worded attack on SYRIZA, which objected to the bond issue, accusing the leftists of being “political parasites that live off the [EU-IMF] memorandum.”

“They should be ashamed of themselves,” he said. “Instead of appreciating this moment of joy for the Greek economy and society, they are miserable.”

Despite the government’s victory lap, Greece is still a mess, it remains stuck in a depression with a political system under duress.

As of January, its unemployment rate was still a staggering 28%, with a youth unemployment rate of 59.7%. As Matt Philips at Quartz notes, Greece’s debt load has actually increased from 148% of GDP in 2010 to 174% today, due to the Greek economy’s collapse:

About 25% of the Greek economy has been destroyed. (To be more precise, it’s 24.8%. During the fourth quarter of 2007 Greece’s GDP was €53.20 billion by the fourth quarter of 2013 it was about €40.01 billion.) Nobody knows if any of it is going to come back any time soon.

Even today, in the wake of the bomb attack on the Bank of Greece, its top labour unions were on strike Thursday in opposition to the budget cuts and tax increases that the ‘troika’ has demanded in exchange for the bailouts, closing just about everything in Athens today. German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble earlier this week reiterated the ironclad position of Brussels and Berlin that Greece will not receive any debt haircut from the troika, though he didn’t rule out the possibility of a third, smaller bailout in the months ahead.

As European elections approach, the leftist, anti-bailout SYRIZA, the Coalition of the Radical Left (Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς) generally leads Samaras’s center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία) by a narrow margin. Venizelos, who leads the center-left PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα), the junior member of the governing coalition, is lucky to draw 5% in surveys.

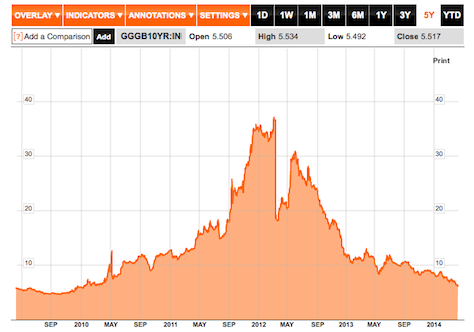

Remarkably, though, Bloomberg quotes a ten-year yield benchmark of around 5.94 for Greece today, down from nearly 40 in the summer of 2012:

Hugo Dixon, writing at Reuters, offers two reasons for the sudden demand for Greek debt:

Hugo Dixon, writing at Reuters, offers two reasons for the sudden demand for Greek debt:

The changed mood in the markets is mainly down to external factors: the European Central Bank’s promise to “do whatever it takes” to save the euro two years ago; and the more recent end of investors’ love affair with emerging markets, meaning the liquidity sloshing around the global economy has been hunting for bargains in other places such as Greece.

Both of those rationales are weaker than they seem, though.

When Mario Draghi, the ECB president, uttered the ‘whatever it takes’ statement, he was clear that it meant that the ECB would do whatever it takes to preserve the euro ‘within our mandate.‘ Though Germany’s constitutional court late last month definitively ruled that the European Stability Mechanism, the €700 billion ($971.6 billion) eurozone bailout scheme, was legal under German law, there’s no guarantee that it will do so as it relates to any action that the ECB takes in the next crisis — or that ‘whatever it takes’ during the next crisis even falls within the ECB’s mandate.

What’s more, with the Federal Reserve and its new chair Janet Yellen ‘tapering’ the quantitative easing programs that the US central bank instituted at the nadir of the US recession and eurozone crises, there’s going to be quite a bit less liquidity in the world these days seeking out opportunities as risky as lending money to Greece.

In framing Greece’s choice as between taking the blue pill (more official financing from the troika) and the red pill (going to the market), FT Alphaville explains why Greece would select the latter:

However, continued reliance on official money would have other, political, costs. Essentially it’s bad news for a sovereign to remain a ward of its public creditors. Again — the official sector looms large over Greece’s existing debt stock anyway, and any buyer of this private bond will have to bear that potential de facto subordination in mind.

But that official debt stock’s already liable to be written off, one way or the other, in future, turning into effective fiscal transfers to Greece. Not counting the IMF of course (it’s senior to all other creditors) — but let’s say the EU loans really do become zero-coupon perpetuals.

Adding further debt to that issue may increase political resistance in Germany (down the line). But more importantly it could increase resentment in Greece. The official money isn’t free: it comes with political strings attached in terms of required “adjustment” and surveillance. Greece is, two years on from its restructuring, just about in possession of current account and primary budget surpluses. Those should normally give Greece a stronger hand with its creditors, not going back cap in hand to them.

But why would investors take such a chance on a sovereign state that’s been in default more often than not in the past 200 years?

One compelling theory is that because the maturity of the troika debt is much longer than today’s debt issuance, investors have little doubt that Greece will be able to service the new debt. Sure, Greece has a huge debt burden, and sure, the troika may ultimately have to grant Greece a haircut, but that will occur a decade or two from now, long after today’s investors are gone:

That Greece is returning to markets at all so swiftly after its 2012 bond restructuring, and with a debt level of over 170% of gross domestic product, might be surprising. But markets have repeatedly shown they have short memories when it comes to sovereign defaults. And Greece’s debt burden isn’t quite what it seems: Around 80% of the debt is in public hands, the average maturity is 16 years, and the average cost of debt is 2.6%, a record low, Citigroup notes. Further relief from Greece’s euro-zone partners might not affect the headline debt-to-GDP level but will make debt service easier. That lowers the risks to private creditors.