Though there’s a long list of world elections approaching between now and the end of May — from Europe to India to South Africa — none of them will have nearly as direct an influence on US foreign policy as the presidential election in a small central Asian country of just 31 million people. ![]()

On April 5, Afghanistan will hold only its third presidential election to select a successor to Hamid Karzai, who’s held the office since December 2001 and who is barred from seeking a third term under the country’s new constitution. By far, the largest challenge for Afghanistan’s new president secure will be to secure the country upon the US troop drawdown that’s expected to be complete by the end of 2014.

It’s a withdrawal that’s already happening. Among the 50,000 international troops in Afghanistan today, just 34,000 are US troops — that’s down significantly from the 101,000 Americans serving in Afghanistan in 2011, which joined a peak NATO force that numbered around 140,000.

After 13 years of US occupation, which followed five years of Taliban rule, which followed seven years of civil war, which followed a decade of Soviet military occupation, which followed six years of coups and skirmishes, there’s not a lot of hope that Afghanistan’s new president will be able to control a country that is historically resistant to central authority. That’s been just as true for Afghan governments (e.g., the Karzai administration) as for foreign invaders, dating back to Alexander the Great and including the ill-fated British attempt to subdue Afghanistan in the late 19th century.

Karzai’s successor may find that he’s essentially the president of Kabul, the Afghan capital, and not much more. It will also be up to the next president to determine whether to enter into a status-of-forces agreement with the United States and its NATO allies to secure a post-2014 role for international peacekeeping efforts that might include up to 10,000 US troops. Karzai has, so far, refused to sign an agreement, though his successor may be more willing to do so. US president Barack Obama has already instructed the US Department of Defense to prepare for a full drawdown:

Obama left the door open, however, for Karzai’s successor — to be chosen in April elections — to sign the pact. “Should we have . . . a willing and committed partner in the Afghan government,” the White House said Obama told Karzai, a “limited” training and counterterrorism force would be in the interests of both countries.

But “the longer we go without a BSA,” or bilateral security agreement, “the more likely it will be that any post-2014 U.S. mission will be smaller in scale and ambition,” the White House said.

Even before his successor is inaugurated, Afghanistan has to make it through the next two weeks of campaigning. After a gun attack at a Kabul hotel restaurant over the weekend, two top international election observers, the National Democratic Institute and the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, withdrew their personnel from the country. That will make it less likely that the April 5 vote is conducted in the absence of fraud.

That’s a major concern after the last presidential election in August 2009, which was conducted amid an equally troubling lack of security. Given the high-stakes circumstances of the 2014 election, however, Afghanistan’s next president can’t afford to be seen as illegitimate from the outset.

On Tuesday, Taliban insurgents attacked the election commission office in downtown Kabul, killing five more civilians. Unsurprisingly, the Taliban-led insurgency is boycotting the election, and it has vowed to use violence to disrupt the voting. That could dampen turnout, which only amounted to between 30% and 33% in the last election, according to a post-vote UN audit.

Afghanistan will choose from among 10 candidates on April 5, and if none of them wins an absolute majority, Afghans will vote in a runoff later in the month.

From Zahir Shah to Taliban insurgency

Afghanistan wasn’t always so unstable.

Mohammed Zahir Shah, the king of Afghanistan between 1933 and 1973, was the first leader to introduce democracy to Afghanistan. Though he was just 19 years old when his father, Mohammed Nadir Shah, was assassinated, Zahir Shah’s uncles effectively ruled in his stead, and they created a relatively modern Afghan state by mid-20th century standards, achieving international recognition and developing trade ties with other Asian and European countries. In the 1950s and the 1960s, Zahir Shah launched a modernization campaign, one element of which was the promulgation of a new constitution that provided for a new parliament, elections, and relatively strong civil rights, including rights for women. In 1973, however, while he was out of the country undergoing eye surgery, his former prime minister Daoud Khan launched a coup d’etat.

Six years later, with the country increasingly torn by ethnic and civil strife, and with Soviet advisers afraid that the United States, China and Pakistan could take advantage of the instability there to build a presence along the Soviet Union’s central Asian border, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, launching what would become a decade-long military quagmire, a disaster that eclipsed even the loss suffered by the United States in its war in Vietnam. Far from stabilizing Afghanistan, the Soviet invasion birthed to the rise of an Islamic mujahideen insurgency against it that drew Muslim fighters from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria and throughout the Muslim world (including Osama bin Laden). Backed with Pakistani and US arms and other military support, the mujahideen forced a full Soviet retreat from Afghanistan by the end of 1989, and the costs of the Soviet invasion were one factor in its subsequent breakup in 1991. Moreover, the Afghan cause provided a rallying point for radical (and not-so-radical) Islamists throughout the region.

The various homegrown mujahideen groups, each with the support of local militias and warlords on the basis of customary and tribal ties, failed to unite after the Soviet withdrawal, allowing the Soviet’s puppet leader, Mohammad Najibullah, to remain in power for three more years. Between 1992 and 1996, Afghanistan descended fully into civil war. During the Soviet War, most of the fighting took place in rural Afghanistan, sending many Afghans fleeing to Kabul, which avoided the brunt of the fighting. But in the 1990s, the fighting centered on Kabul, as insurgents from the north and the south battled the central government to take control of the capital, which was reduced to rubble as a result. Meanwhile, with the end of the Cold War, neither Russia nor the United States cared much about Afghanistan’s descent into chaos.

The Taliban emerged under the leadership of Mullah Mohammed Omar in the mid-1990s, and it quickly brought an end to the civil war by rapidly taking control of, first, Afghanistan’s south, and then the whole country, beginning in 1996. While in power, the Taliban introduced severe restrictions on political liberties in line with shari’a. Women were no longer allowed to work, and they were only allowed to appear in public in a full burqa. The Taliban banned music, cinema, dancing and other decadence they believed to be contrary to Islam, in a religious regime that made the Islamic Republic of Iran seem liberal in comparison. The Taliban increasingly sanctioned bin Laden and the training camps for al-Qaeda. That decision, fatefully, made the Taliban the top target of the United States after al-Qaeda’s September 2001 terrorist attacks.

It took the US military a matter of days to sweep the Taliban out of power in November 2001, introducing the government that Karzai now leads. But top Taliban officials fled across the border to Pakistan alongside al-Qaeda leaders, and they regrouped for what has become a tenacious insurgency. In 2002, the US military and policymakers became increasingly focused on what would become the 2003 invasion of Iraq. As the 2003 invasion turned into a full-fledged occupation, the US military found itself drawn into an increasingly troubling Sunni insurgency in Iraq, which by 2007-08 had descended into sectarian violence. The initial US push into Afghanistan became a lower priority, and the Taliban insurgency gained ground. With Karzai’s government on corrupt autopilot in Kabul, the Taliban retook nearly half of the country, including Helmand and Kandahar provinces in the south of Afghanistan, the rural hinterland surrounding the city of Kandahar. By the end of 2008, Afghanistan opium poppy production had skyrocketed, fueling the growing demand for heroin globally, and financing the newly empowered Taliban insurgency.

US president Barack Obama refocused the US military on Afghanistan, especially after the US withdrawal from Iraq, and NATO forces have had some success in reducing the Taliban’s control in southern Afghanistan.

The worst fear of US and Afghan government officials alike, however, is that after the US force leaves Afghanistan later this year, much of the country could fall back into Taliban control. That, in turn, could result in another period of civil war, like the kind that followed the Soviet occupation.

That’s also why the growing violence in the lead-up to the election is so troubling. If the Taliban can cause so much mischief, even in the heart of Kabul, where the central government is at its strongest, and with an international force of 50,000 troops to provide security, imagine the damage it could do in 2015 after that international security force is gone.

Avoiding another 2009

As if it weren’t difficult enough to conduct a national election in a country significantly disrupted by the Taliban insurgency, there’s a good chance that Afghanistan’s citizens won’t even respect the vote because of the likelihood of fraud. That’s why it will be vital for Afghanistan to avoid the spectacle of the 2009 election.

In that campaign, Karzai was running for reelection against Abdullah Abdullah, foreign minister between 2001 and 2005, and the candidate of a united front that included many of the leaders of the Northern Alliance, the Tajik-dominated military force that helped the United States vanquish the Taliban so quickly in 2001.

Vote-counting took nearly a month, and as the election commission released partial results over the course of August and early September, Karzai’s once-marginal lead over Abdullah kept growing. Karzai’s supporters argued that it was because the first votes to be counted were predominantly from the northern part of the country, where support for Karzai, a southern Pashtun, was weakest. Yet as counting continued, Abdullah and other international observers found serious problems with the entire electoral process, including many instances of ballot-stuffing and other forms of fraud.

On September 16, the election commission released final uncertified results that gave Karzai 54.6% of the vote, a margin large enough to avoid a runoff — but not if all of the suspected fraudulent votes were invalidated. Throughout October, international observers gathered increasing evidence of widespread fraud, and US and other officials pressured Karzai to find a solution to what was quickly becoming a national crisis.

With US and European demands for a runoff increasing, and with the Obama administration threatening to withdraw troops from Afghanistan, Karzai finally relented on October 20, and the election commission released the ‘final’ results a day later, giving Karzai just 49.67% of the vote, with Abdullah winning 30.59%.

The runoff was scheduled for November 7, and both Karzai and Abdullah immediately turned to campaign mode. Six days before the election, on November 1, Abdullah withdrew from the runoff, in protest that no fair vote was possible, in part because the composition of the election commission hadn’t changed.

The runoff was canceled and Karzai was declared the winner the next day.

The entire debacle showed just how corrupt governance in Afghanistan had become under Karzai, massively reduced the legitimacy of Karzai’s government, and set the tone for the increasing distance that would mark Karzai’s relations with the US government under the Obama administration — in stark contrast to George W. Bush, who went out of his way to court Karzai’s favor.

A month later, the Obama administration bolstered the US military effort with a ‘surge’ of 30,000 troops that helped retake some of the territory in the Afghan south from the Taliban. But in 2010, civilian deaths hit a new high during what was then already a nine-year US campaign, and the September 2010 parliamentary elections were marred with the same level of insecurity and fraud as the previous presidential election. Throughout 2011, Taliban insurgents continued to wage a deadly campaign, and between July and September, they assassinated both Karzai’s half-brother Ahmad Wali Karzai, then the governor of Kandahar, and Burhanuddin Rabbani, who served, at least in name, as Afghanistan’s president between 1992 and 1996.

Afghanistan’s constituencies

All of the major candidates are Pashtun, the dominant ethnic group in Afghanistan (except Abdullah, who is half-Pashtun and half-Tajik).

Most of Afghanistan’s leaders over the last century have been Pashtun — the two notable exceptions are Rabbani, who was ethnically Tajik, and Babrak Karmal, also Tajik and the first Marxist leader propped up by Soviet occupation between 1979 and 1986. Though Karzai and the top candidates are all Pashtun, it’s also worth noting that the Taliban is also almost exclusively comprised of Pashtuns as well.

Pashtuns, generally speaking, constitute about 42% of the population, and they predominately occupy a crescent arc that swoops through the center, east and south of Afghanistan, stretching from the Pakistani border to Kandahar in the south and back up to Herat. Another 30 million Pashtuns live in Pakistan, in Khyber Pakhtunkwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas that, for over a decade, have provided sanctuary for al-Qaeda and other anti-US forces (and plenty of forces hostile to the central Pakistani government as well).

Tajiks, which constitute around 27% of the population, are located mostly in the northeast of the country along the Afghan border with Tajikistan, including the largest city in the north, Mazar-e Sharif. They predominantly populated the Northern Alliance that in 2001, with US military forces, took control of the country. Tajiks form the largest ethnic group within Kabul (around 45%, with Hazaras and Pashtuns comprising around 25% each).

Uzbeks, which constitute around 9% of the population, are clustered throughout the north-central part of the country. Like the Tajiks, the Uzbeks played a prominent role in the Northern Alliance.

Hazaras, which also constitute around 9% of the population, speak Dari (Afghan Persian) and they live chiefly within the central highlands of the country. Hazaras mostly adhere to Shi’a Islam, in contrast to the Sunni Islam otherwise dominates Afghanistan, and they suffered significant persecution during the Taliban era.

Balochs, which constitute just 1% or 2% of the population, dominate the most sparsely populated far south, nudged between Iran and Pakistan’s Balochistan province. The Balochs aren’t numerous enough to impact the presidential election, but the ongoing Balochi secession movement is a factor that could add an element of instability.

The candidates

Whether Afghanistan’s elections and transition go smoothly depends as much on the candidates as the Karzai administration. If a losing candidate, rightly or wrongly, fails to recognize the winner, it could immediately undermine the new government.

Generally, the race features three frontrunners, each of whom has worked as either a finance or foreign minister in previous Karzai-led governments. If the race proceeds to a runoff, the two final candidates will almost certainly vie strongly for the support of the third frontrunner. That’s especially true in Afghanistan, where elections are won and lost by amassing networks of warlords and local tribal leaders, who can thereupon deliver votes to a particular candidate.

Abdullah Abdullah

Abdullah, 53, is the runner-up in the flawed 2009 presidential election, and he served as the country’s foreign minister in the first four years of post-Taliban rule. An eye surgeon by training, Abdullah also served as deputy foreign minister in Rabbani’s weak government between 1992 and 1996. During the Soviet occupation, Abdullah fought alongside Ahmad Shah Massoud, a leading Tajik insurgent (Massoud, who would eventually become the most capable leader of the Northern Alliance, was assassinated on September 9, 2001, just two days before the al-Qaeda terrorist attacks).

He’s generally viewed as the frontrunner in the current race, in light of his dual ethnicity, which has earned him support among both the Pashtun and the Tajik electorates. Abdullah hopes to build an even larger tent of supporters, though — his vice-presidential candidates are Mohammad Khan, a former leader of Hezb-i-Islami, another Pashtun insurgent group; and Mohammad Mohaqiq, a top Hazara leader. Neither Khan nor Mohaqiq are uncontroversial, they are both essentially ‘warlords,’ and they have both been accused of human rights violations during Afghanistan’s violent past.

Since the 2009 election, Abdullah has worked to build a grassroots democratic coalition to check Karzai’s administration and to prepare for the presidential election. In that regard, Abdullah has become one of Karzai’s sharpest critics, blaming Karzai for taking ’emotional’ decisions and for having no vision for Afghanistan. Abdullah has also criticized Karzai for his obstinacy over a bilateral security agreement. In contrast to Karzai, Abdullah said he would sign an agreement with the Obama administration within a month of his election.

Zalmai Rassoul

Rassoul, 70, hasn’t been endorsed by Karzai, but he’s widely viewed as the Karzai administration’s favorite. Rassoul served as Karzai’s foreign minister between 2010 and October 2013, when he resigned in order to stand for the presidential election. Previously, he served as Karzai’s civil aviation minister.

The link between Rassoul and Karzai became stronger when Karzai’s brother, Quayum Karzai, dropped out of the presidential race and backed Rassoul on March 6.

Rassoul is a member of the Mohammadzai tribe, the same as the Afghan monarchy that ruled the country between 1826 and 1973, and he served as a top official to Zahir Shah in exile in Italy between 1973 and 2002. But there are reasons to doubt that Pashtuns will necessarily rally behind Rassoul’s candidacy. His Pashto language skills aren’t incredibly strong, he’s unmarried, and he’s spent most of his adult life living in Kabul and the West, all of which could breed skepticism among conservative Pashtun voters. Moreover, his ties to the unpopular president (and his even more unpopular brother, who’s been dogged by accusations of corrupt business dealings) may cause as much harm as any unofficial support that Karzai might provide.

His vice-presidential running mates include Ahmad Zia Massoud, an ethinic Tajik and the brother of the late Northern Alliance general, and Karzai’s vice president between 2004 and 2009; and Habiba Sarobi, a Hazara, and the governor of Bamyan province, the first female governor in Afghan history.

Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai

Ghani, 65, very nearly became Kofi Annan’s successor as the secretary-general of the United Nations in 2006.

Though he missed out on winning the UN’s top job, Ghani has the highest international profile, by far, of any of the candidates in the 2014 election. He earned his university degree in Lebanon, where he met his wife, a Christian. He left in 1977 for the United States, and he remained there throughout much of the next quarter-century, teaching at Johns Hopkins University in the 1980s and serving as a World Bank official in the 1990s. After 2001, Ghani returned to Afghanistan, where he worked with the UN special representative Lakhdar Brahimi to develop what would become the Bonn Agreement that outlined the transfer of power from US forces to Afghan leaders. During the interim government, Ghani served as finance minister, and he won domestic and international praise for stabilizing Afghanistan’s treasury after years of neglect.

In 2004, after Karzai won his first formal term as president, Ghani was appointed chancellor of Kabul University. Though he stood in the 2009 presidential election, he finished far behind in fourth place, with just 3% of the vote.

This time around, Ghani seems much more serious about winning the election, and he’s formed an improbable alliance with Abdul Rashid Dostum, an ethnic Uzbek and a former insurgency leader that Ghani once labeled a killer. Though Dostum supported the Soviets against the mujahideen during the 1980s, he fought fiercely against the Taliban, both before and after the US effort in 2001. Even today, Dostum still commands control of a personal army in Afghanistan’s Uzbek north. But the alliance between the urbane, internationalist presidential candidate and one of Afghanistan’s most notorious warlords could deliver many Uzbek voters in support of Ghani’s bid.

Ghani has also selected a Hazara as his second vice-presidential candidate — Sarwar Danish, who has served as governor of Diakundi province since 2004 and minister of justice from 2004 to 2010, and who currently serves as minister of higher education.

Like Abdullah, Ghani has criticized Karzai for dithering over a bilateral security agreement, and he has pledged to sign an agreement as one of his first acts as president. Like Rassoul, he’s a technocrat at ease in the world of international relations. Though Washington is officially neutral in the presidential election, there’s no doubt that many US policymakers are privately rooting for Ghani.

The rest of the field

The remaining seven candidates are unlikely to advance to a runoff, but their showings on April 5 could make them very valuable to the candidates who advance to a runoff and to the net Afghan government.

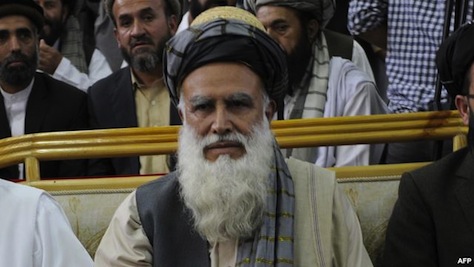

Perhaps the most compelling wild card in the race is Abdul Rasul Sayyaf (pictured above), a religious scholar who was instrumental in al-Qaeda’s rise in Afghanistan in the 1980s and who was once identified as a spiritual leader to Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, one of the key planners behind al-Qaeda’s 2001 attacks.

Despite his ties to radical Islamists, he joined the Northern Alliance in opposition to the Taliban, one of the few Pashtun warlords to do so. Sayyaf has harshly criticized the insurgency and some of its tactics, including suicide bombings, as disloyal to Islam. Since 2001, Sayyaf has been a member of Afghanistan’s parliament, and he’s clear a Pashtun leader that even Karzai respects.

But Sayyaf is nearly as anti-Western as he is anti-Taliban, and he could win votes from former Taliban supporters. He’s named Ismail Khan, a Tajik warlord from Herat (the largest city in western Afghanistan) and energy and water minister since 2005, as one of his running mates.

Though he’s unlikely to win the election, Sayyaf could deliver a key constituency of Pashtun voters in a runoff. He could also play an even more important role in post-election, post-occupation talks between the Afghan government and Taliban insurgents.

Qutbuddin Hilal, a Pashtun leader with ties to Hezb-i-Islami, which has taken an active role in the current insurgency, has been endorsed by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the longtime insurgent and leader of Hezb-i-Islami who has fought both the Soviets and the US-led NATO forces.

Gul Agha Sherzai, one of the top military leaders who captured Kandahar in 2001 alongside Karzai and US forces, is nicknamed the ‘Bulldozer.’ A Pashtun with strong ties to Kandahar province, he served as the governor of the province in the 1990s and from 2001 to 2003; in 2004, he became the governor of Nangarhar province.

Two well-known officials, both Pashtuns, who don’t seem to have amassed significant support include Abdul Rahim Wardak, defense minister from 2004 to 2012, and Hedayat Amin Arsala, a former foreign minister between 1993 and 1995, and the interim vice president between 2001 and 2004.

Top photo credit to Reuters/Goran Tomasevic