In a decision that could widely affect the May presidential election, Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos has confirmed the previous decision of Colombian inspector-general Alejandro Ordóñez to remove Gustavo Petro, a leftist and former M-19 rebel leader, as Bogotá’s mayor.![]()

Ordóñez, a staunchly right-wing conservative close to former president Álvaro Uribe, ordered Petro’s removal last December on the questionable basis of Petro’s actions during a garbage collection strike in December 2012. Ordóñez claimed that Petro’s threat to replace public workers with private garbage collectors amounted to abuse of office. In addition to Petro’s removal, Ordóñez also banned Petro from holding public office for 15 years.

* * * * *

RELATED: Uribe returns to Colombian political life as senator

* * * * *

Petro, who was facing an April 6 recall election in any event, appealed Ordóñez’s decision, but the Colombian Council of State refused to overturn it. Santos affirmed Petro’s removal today, naming labor minister Rafael Pardo as Bogotá’s interim mayor, despite an order from the Inter-American Human Rights Commission upholding Petro’s right to remain mayor. Accordingly, Santos’s decision could potentially endanger Colombia’s seat within the Organization of American States.

Presumably, Bogotá residents will go to the polls later this spring or summer to choose Petro’s permanent replacement.

In the meanwhile, Santos’s decision leaves him vulnerable on at least three fronts as the May 25 presidential election approaches. Santos appears increasingly likely to face a June 15 presidential runoff, against either former Bogotá mayor Enrique Peñalosa or former finance minister and Uribe ally Oscar Ivan Zuluaga, the candidate of Uribe’s newly formed politics vehicle, Centro Democrático (Democratic Center).

1. Petro’s removal could cause the Colombian left to rally further around Peñalosa

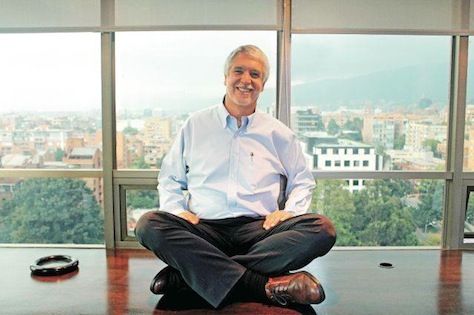

Just days after Peñalosa (pictured above) won the nomination of the Alianza Verde (Green Alliance), he has already become the main threat to Santos’s reelection bid.

A Datexco/El Tiempo poll taken between March 13-14 shows that Santos still leads the first-round vote with 25.5% support, roughly the same as in previous polls. Undecided voters, however, are starting to choose among various opponents — Peñalosa has leapt to second place with 17.1%, and Zuluaga is close behind with 14.6%. The candidate of the leftist Polo Democrático Alternativo (Democratic Alternative Pole), Clara López, wins 10.7% and the candidate of the Partido Conservador Colombiano (Colombian Conservative Party), Marta Lucía Ramírez, would win just 7.7%.

In a runoff, the poll showed that Santos would easily defeat Zuluaga by 45.7% to 28.3%. But Peñalosa narrowly led Santos by 40.4% to 37.3% in the June runoff, and it’s the first presidential poll I’ve seen that shows that Santos could lose reelection. Santos is still probably the favorite, but the race is definitely tightening.

The Green Alliance is a coalition that formed in September 2013, uniting Peñalosa’s Partido Verde Colombiano (Colombian Green Party) and Petro’s considerably more leftist Movimiento Progresistas (Progressive Movement).

That means that the Green Alliance is somewhat more to the left of the coalition of parties that support Santos, including the Partido Liberal Colombiano (Colombian Liberal Party) and the Partido Social de Unidad Nacional (Social Party of National Unity, ‘Party of the U’). The Party of the U is a spinoff of former Liberals that supported Uribe throughout the 2000s.

But Peñalosa is much more moderate than the party that he’s leading. Like Antanas Mockus, also a former Bogotá mayor and the 2010 Green Party presidential candidate, Peñalosa is associated with the progressive urban policies that astonishingly revitalized Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, over the last decade. Unlike Mockus, who lost the 2010 runoff to Santos in a landslide defeat, Peñalosa is a pragmatic, business-friendly politician who was once a member of the Liberal Party himself. He will be able to woo moderate voters away from Santos to a degree that Mockus never could, especially outside Bogotá (a city receptive to leftist politics in an otherwise very conservative country).

The Green Party’s 2014 alliance with the Progressive Movement pits Petro and Peñalosa ostensibly on the same team. But Petro defeated Peñalosa in the October 2011 Bogotá mayoral election, and Peñalosa isn’t about to endorse Petro’s socialist agenda anytime soon. They’re allies of convenience, but not much more. Peñalosa and Petro appeared to reconcile last month as Peñalosa tried to wrap up the Green Alliance’s presidential nomination and, earlier today, Peñalosa also denounced Petro’s removal as undemocratic on Twitter:

No es democrático que a un líder como Petro le quiten los derechos políticos, sin que haya habido corrupción o fallo de un juez

— Enrique Penalosa (@EnriquePenalosa) March 20, 2014

Peñalosa needs Petro and his progressive supporters to fuel his path to the June presidential runoff — and those progressive voters certainly now have a reason to fight hard against Santos’s reelection. Peñalosa’s opposition to Petro’s heavy-handed dismissal could win Peñalosa credibility among the Colombian left, which remains skeptical of his presidential candidacy. Progressives within the alliance would have certainly preferred a more leftist candidate, such as senator-elect Antonio Navarro, who comes from the Progressive camp and is one of Colombia’s most respected leftists.

But if he can make it to the runoff, Peñalosa will almost certainly command the united support of the Green-Progressive front, and he stands to win many of the Democratic Pole supporters that will vote for López in the first round.

2. Petro’s removal could damage the ongoing Colombian-FARC talks

One of the most sensitive aspects of the Petro case is Petro’s own background as a member of the M-19 rebel group. The April 19th Movement formed in 1970, and like the older Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), it was a leftist guerrilla militia that opposed the Colombian government at the time. Petro, who spent 18 months in jail in the 1980s, later worked to bring M-19 into negotiations with the Colombian government that smoothed the way for former M-19 rebels like Petro and Navarro to participate in electoral politics.

But Petro’s removal only fuels speculation that the Colombian right is still working in the shadows to hamstring and harass former leftist guerrillas in Colombian politics, notwithstanding prior negotiations and settlements.

You can see how that could worry FARC militants, who are now also working through a political negotiation with the Colombian government. Peace talks began in November 2012, and the effort is the most important element of the Santos administration’s first-term agenda. The future political participation of FARC guerrillas is one of the five major issues that Colombian government and FARC negotiators are working to resolve during the Havana talks. Those negotiations were moving slowly enough without complications from the Petro case, but the heavy penalty that Ordóñez imposed, and Santos’s validation today could cause FARC negotiators to think twice about signing a final peace deal with the Santos administration. After all, if the Colombian government won’t — or can’t — keep to the terms of its agreement not to harass former M-19 rebels, there can be no guarantee that future FARC politicians will avoid similar difficulties. That’s especially true so long as a significant segment of the Colombian right, under Uribe’s leadership, opposes the FARC negotiations.

3. The ratification of Ordóñez’s decision could encourage Uribe’s allies to push harder against the Santos administration

If Santos (pictured above) does win reelection, he’ll face a much different political environment for the next four years than he did in the past four years because he will not be working with a pliant majority in Colombia’s Congreso (Congress) — perhaps a good development for the growth of Colombia’s democratic institutions, but also perhaps a sign of future gridlock between the Santos and Uribe camps. After the March 9 parliamentary elections, though the Santos-led coalition should continue to hold a majority in the lower house, the Cámara de Representantes (Chamber of Representatives), its majority is by no means assured in the upper house, the Senado (Senate).

Though he initially supported Santos, his former defense minister, in 2010, Uribe quickly turned against Santos, and he fiercely opposes Santos’s approach to FARC negotiations. Not only did Uribe win a seat in the Senado this month, but the Democratic Center and the Conservatives (currently divided between the Santos and Uribe camps) now control nearly 40% of the chamber, while Santos and his allies control about 45%.

Ordóñez’s decision in the Petro case is a reminder that many Uribe partisans remain in key positions within the Colombian government. Santos’s affirmation of the Ordóñez ruling could further encourage Uribe allies within the government to take aggressive stands in the future — not only with respect to Bogotá, but to Santos himself. The Petro case, especially after the success of the Democratic Center in the recent elections, will only embolden Uribe, who will be certain to make as much trouble for Santos as possible between now and 2018 (if Santos wins reelection).

Top photo credit to Kevin Lees — Bogotá, Plaza de Bolívar, August 2011.