The big headline from Sunday’s congressional elections in Colombia is the return of the powerful conservative former president, Álvaro Uribe, who won election to the Colombian Senado (Senate).![]()

But the bigger story is more complicated — and the truth is that each of the two major camps in Colombian politics has something to be happy about from the weekend’s elections, which were conducted in the shadow of two important upcoming elections — a recall election involving Gustavo Petro, the leftist mayor of Bogotá on April 6 and a presidential election on May 15 (with a potential runoff to follow later in the summer).

Uribe (pictured above) has carved out a space where he now leads the main opposition to Colombia’s president Juan Manuel Santos, demonstrating his enduring popularity and his determination to play a role in Colombian governance, despite his ineligibility to run for the presidency in the future. It will make Colombia’s congress a much livelier place, to say the least, and it will require Santos (or his successor) to work hard to maintain a working majority in the Colombian congress, and especially in the Senado.

Santos, however, should be delighted that his coalition suffered only marginal losses to Uribe’s forces. Despite Uribe’s gains on Sunday, Santos remains the heavy frontrunner in the upcoming May 15 presidential election. That’s in part because Uribe himself is barred from reelection, so Uribe’s new party is supporting former finance minister, Óscar Iván Zuluaga, who has far less popularity and charisma than either Uribe or Santos.

You can think of Colombia politics today as a competition between two major blocs — a centrist/center-right coalition that supports Santos and a more conservative bloc that supports Uribe. In addition, there’s a minor bloc of leftist parties that today find themselves largely outside the mainstream of Colombian politics, with the exception of the Colombian capital, Bogotá.

Uribe formed  the Centro Democrático (Democratic Center) last year, and he ran on the slogan of ‘mano firme, corazón grande,’ or ‘firm hand, big heart,’ campaigning in opposition to Santos’s high-profile push to negotiate a lasting peace settlement with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). While Uribe should be happy with the results of the senatorial elections, it’s clear that the ‘Uribe bloc’ is still far smaller than the ‘Santos bloc,’ which includes three major parties:

the Centro Democrático (Democratic Center) last year, and he ran on the slogan of ‘mano firme, corazón grande,’ or ‘firm hand, big heart,’ campaigning in opposition to Santos’s high-profile push to negotiate a lasting peace settlement with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). While Uribe should be happy with the results of the senatorial elections, it’s clear that the ‘Uribe bloc’ is still far smaller than the ‘Santos bloc,’ which includes three major parties:

- The Partido Liberal Colombiano (Colombian Liberal Party), once Colombia’s largest center-left party, has converged with the other parties in the Santos-led coalition, pulling it ever closer to the center-right in recent years. The party split over whether to support Uribe, who began his political career in the Liberal Party. Though it fielded separate presidential candidates in both 2006 and in 2010, it will support Santos in 2014.

- The Partido Social de Unidad Nacional (Social Party of National Unity, ‘Party of the U’) is a conservative party formed in 2005 by Liberal uribistas, and the ‘U’ once stood as much for Uribe as for ‘unidad.’ It became Colombia’s largest party in the Uribe era, and it now forms the backbone of Santos’s coalition.

- Cambio Radical (Radical Change), founded in 1998, became increasingly important over the course of the 2000s, and it formed part of Uribe’s presidential majority in the 2000s, just as it today forms part of Santos’s presidential majority. Like the Party of the ‘U’ and the Liberal Party, it will support Santos in the upcoming presidntial election.

The major swing vote between the two blocs is the Partido Conservador Colombiano (Colombian Conservative Party). Like the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party dates back to the 1840s, and it was once Colombia’s chief center-right party. It’s currently part of Santos’s coalition, but it’s the weakest link among the four parties that have backed Santos since 2010, and it’s the likeliest source of future support for Uribe. Though it supported Uribe in 2002 and 2006 and Santos in 2010, it is fielding its own presidential candidate in 2014, Marta Lucía Ramírez, a former senator and defense minister between 2002 and 2003. That hurts Santos by depriving him of the Conservative brand (though only a few Conservative lawmakers have actually endorsed Ramírez), but it also hurts Uribe and Zuluaga by dividing the conservative opposition to Santos.

Uribe guided Colombia’s transition from a country paralyzed by drug-related violence into a more secure, economically vibrant regional leader between 2002 and 2010, backed by the military and economic aid of the US government. Despite efforts to run for a third term, Uribe bowed out of the presidency in support of Santos, his defense minister. Santos (pictured above) easily won election in June 2010, king nearly 70% of the vote in a runoff against Bogotá mayor Antanas Mockus, the candidate of the Partido Verde Colombiano (Colombian Green Party).

Almost immediately, however, Uribe started criticizing Santos, and Uribe irrevocably broke with his one-time protégé when Santos directed the Colombian government to enter into negotiations with FARC, a leftist guerrilla group that has waged an insurgency against Colombia for the better part of the last half-century.

If Santos succeeds in winning a truce with FARC, it will represent the end of an ideological conflict that goes back to the liberal/conservative civil wars of the 19th century, and that has its immediate roots in the 1948 assassination of popular liberal politician Jorge Eliécer Gaitán and La Violencia, the ensuing decade-long wave of attacks and counterattacks. Despite FARC’s waning popularity, it plays a role in South America’s cross-border drug trade, making it one of the Colombian government’s top nuisances.

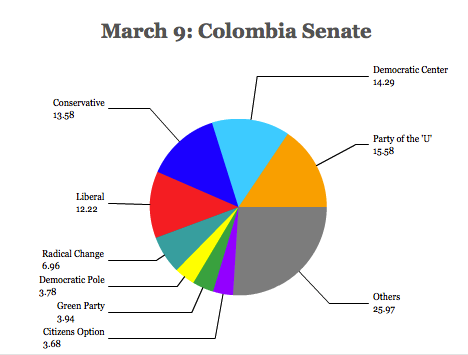

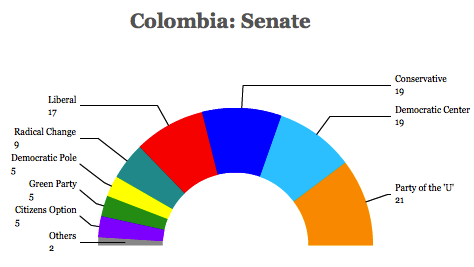

In light of this background, let’s take a look at the actual results from Sunday’s vote. Here are the current vote totals for the senatorial election and the projected seats for the 102-member Senado:

What’s most clear from the actual results is that no single party won more than 16% of the vote nationwide, and the four major parties — Liberal, Conservative, Democratic Center and Party of the U — essentially all won a similar chunk of the senatorial vote.

What’s most clear from the actual results is that no single party won more than 16% of the vote nationwide, and the four major parties — Liberal, Conservative, Democratic Center and Party of the U — essentially all won a similar chunk of the senatorial vote.

If Santos holds on to the support of the Conservatives, he’ll easily control a senatorial majority (66); if the Conservatives back Uribe, the Senado will be much more divided, with the Santos bloc (47) only narrowly outnumbering the Uribe bloc (38).

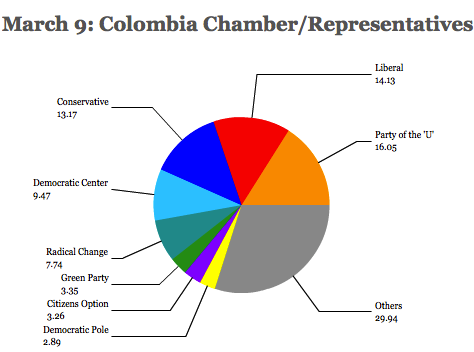

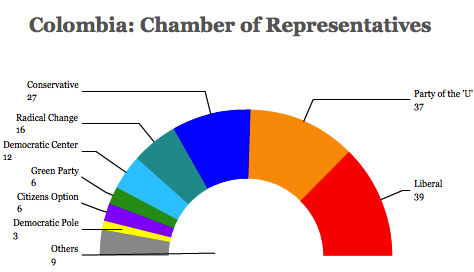

In the Cámara de Representantes (Chamber of Represenatives), it’s something of a different story, because Uribe’s Democratic Center didn’t do nearly as well as in the senatorial election — it fell behind each of the Party of the U, the Conservatives and the Liberals, and it may wind up with even fewer seats than Radical Change:

Though the results aren’t completely final and the ultimate seat totals will shift to some degree, it’s clear that, even without the Conservatives, the Santos bloc will hold a majority (92) in the lower house of the Colombian Congress.

It’s somewhat of a more pessimistic story for the Colombian left. The Polo Democrático Alternativo (Democratic Alternative Pole) lost three of its senatorial seats, and while the Green Party held on to its five seats, it made no gains. Neither party is close to Uribe or to Santos, but both groups largely support the Colombian government’s peace initiative, which gives Santos a potential reservoir of support for his administration’s top effort from groups that would typically be among his fiercest ideological opponents.

On Sunday, the Green Party chose its candidate for the presidency, former Bogotá mayor Enrique Peñalosa, who could ultimately wind up as the strongest rival to Santos’s bid for reelection. With Zuluaga and Ramírez struggling to win support, Peñalosa could unite what’s left of the leftist opposition to Santos.

Peñalosa served as Bogotá’s mayor between 1998 and 2001 (sandwiched between Mockus’s two terms from 1995-97 and 2001-03), and Peñalosa has developed a reputation as a somewhat business-friendly mayor who, along with Mockus, transformed the public face of Bogotá. His relatively conservative reputation, however, was one of the reasons he failed to win another term as mayor in the subsequent 2007 and 2011 elections.

Santos holds a wide lead over all current challengers, according to a Datexco/El Tiempo poll conducted February 25-28: Santos wins 24.4% to just 6.3% for Zuluaga, 6.3% for Peñalosa and 4.1% for Ramírez, though 41.5% said they would cast a blank vote and 8.6% said they didn’t yet know who they would support. Other polls show Santos with a wider lead (and with fewer abstentions).