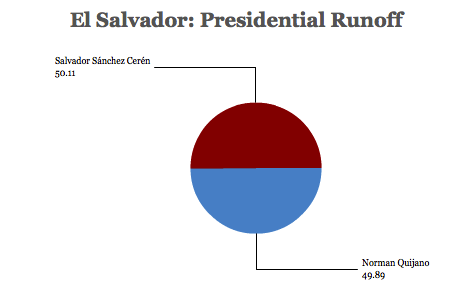

Though El Salvador’s vice president, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, was expected to win the March 9 presidential runoff, the result was so tight that no winner has yet been formally declared, pending a recount of the too-close-to-call election.![]()

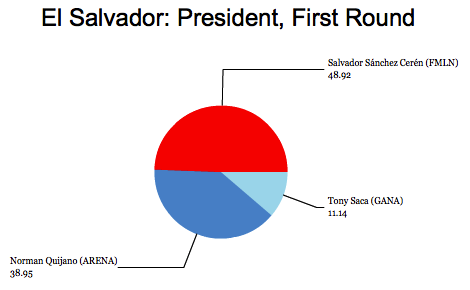

Sánchez Cerén (pictured above, left, with running mate Óscar Ortiz, right) almost won the presidency outright in the first round on February 2, taking 48.92% of the vote, a nearly double-digit lead over his challenger, San Salvador mayor Norman Quijano, who won just 38.95%:

Sánchez Cerén hopes to extend the rule of the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN, Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front), the one-time guerrilla group that is today El Salvador’s major leftist political party. In 2009, Mauricio Funes, a former journalist, led the FMLN to its first-ever electoral victory, ending nearly two decades of post-civil war rule by the center-right Alianza Republicana Nacionalista (ARENA, Nationalist Republican Alliance).

On Sunday, however, provisional results show that Sánchez Cerén won just 50.11% of the vote, narrowly leading Quijano, who had 49.89% of the vote:

How did this happen?

It wasn’t too difficult to realize, even before February 2, that the runoff vote would tighten. That’s because in the first round, Sánchez Cerén easily consolidated the FMLN vote, while Quijano had to compete against Elías Antonio ‘Tony’ Saca, a conservative who served as president from 2004 to 2009. Saca, following his presidency, was kicked out of ARENA, largely over allegations of corruption stemming from his presidential administration and his future presidential ambitions. Accordingly, Saca led a third-party coalition against both Quijano and Sánchez Cerén in 2014.

Though Saca won a relatively disappointing 11.44% in the first round, it seemed clear that Quijano would win the majority of Saca supporters in the second round. Taken together, the combined Quijano-Saca support totaled 50.39%, proving in the first round that there’s a basis for a center-right, conservative electoral coalition. If Quijano were able to win almost all of the former Saca voters and/or win over a few first-round FMLN voters, he could leapfrog Sánchez Cerén and into the presidency. Sunday’s provisional result seems to indicate that, though Quijano consolidated much of the conservative vote, it still wasn’t quite enough (though let’s wait for the full recount).

Quijano waged a strong campaign over the last month, playing on fears about Sánchez Cerén’s radicalism. Unlike Funes, Sánchez Cerén came to politics directly from the Salvadoran civil war, where he served as one of the FMLN’s top field commanders. It’s one thing for Salvadorans to elect a social democratic president whose roots lie outside the FMLN’s guerrilla struggles of the 1970s and the 1980s. It’s another thing to elect a strident leftist who was calling the shots on one side of the civil war three decades ago. No matter the pragmatism of the Funes administration, no matter the moderation of Sánchez Cerén’s vice presidential candidate, Óscar Ortiz. Quijano easily stirred doubts about a Sánchez Cerén presidency, and plenty of conservatives in the United States sounded an international alarm over the consequences of an FMLN victory on Sunday.

If Quijano pulls off a victory in the final count of Sunday’s vote, he will have convinced sufficient numbers of centrist Salvadoran voters the risks of Sánchez Cerén making a sharp left turn were simply too high (including at least a handful of overseas Salvadoran voters in the United States and elsewhere abroad, who could vote in the presidential race for the first time and who lean significantly more left than the domestic Salvadoran electorate). It won’t be much of a mandate for Quijano’s leadership or for the ARENA approach to crime, security or economic policy. Quijano is close to former president Francisco Flores, who is under investigation for corruption charges himself.

If Sánchez Cerén pulls off a victory, it will be thanks largely to the FMLN and the legacy of the Funes administration. (It will also help that Saca refused to endorse either candidate, depriving Quijano, in particular, of another tool that could have united the conservative electorate.)

Salvadorans, by and large, seem relatively content with the past five years of the Funes presidency. Ineligible for reelection, Funes significantly expanded social welfare in El Salvador — he abolished health care fees, introduced new literacy programs, provided food and clothing for schoolchildren, granted title to disputed land, introduced monthly stipends and job training for poor Salvadorans. He also introduced anti-discrimination legislation for women, indigenous communities and sexual minorities. Funes controversially (and secretly) negotiated a truce in 2012 between El Salvador’s two fiercest gangs, Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18, which led to a fragile peace between the two gangs and an appreciably lower homicide rate. He also moved El Salvador closer to the socialist countries that comprise the Venezuela-led Alianza Bolivariana (ALBA, Bolivarian Alliance), opening new opportunities for Salvadoran business, while retaining traditionally strong ties with the United States.

Funes occupied the business-friendly lulista left without falling far into the more radical chavista left, and that’s what Salvadoran voters will now expect of Sánchez Cerén, if he prevails. If Sánchez Cerén has any kind of mandate in such a narrow victory, it’s that voters expect him to keep El Salvador on the same center-left path as the Funes administration. Any attempt to introduce the kind of socialist expropriation or nationalization efforts that we’ve seen in countries like Venezuela would be controversial. Attempts to eliminate the presidential term limit, in the same manner as Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega (or as former Honduran president Manuel Zelaya attempted in 2009), would be controversial. Attempts to move El Salvador closer to ALBA and Venezuela, or away from the United States (the destination of 45.8% of Salvadoran exports and the source of remittances that comprise 28.2% of Salvadoran GDP) would be controversial.

There’s also the question of fraud. Reports of shady deals between the FMLN and Salvadoran street gangs to round up voters may or may not be credible, but the allegations should be taken seriously, though it’s important to keep in mind that ARENA isn’t immune to charges of impropriety in its time in power either. But with such a narrow lead, it would compromise Sánchez Cerén’s presidency (and the largely positive legacy of the Funes administration) if there’s significant doubt about the legitimacy of the vote.