Despite what you may believe from the example of Egypt and from the various ‘color’ revolutions of the past decade, power isn’t transferred by popular revolt, at least not in mature democracies.![]()

That’s important to bear in mind as much of the US and international media keeps its attention focused on Kiev, where protesters continue to demand the resignation of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, who is largely seen as favoring closer ties to Russia than to the European Union and the West. Despite last weekend’s protests of up to 250,000 Ukrainians, which featured violent clashes with the police (the Ukrainian government has since apologized), Yanukovych has so far survived the blowback from his decision last month to reject an association agreement that would have brought Ukraine into closer alliance with the European Union. While the most conspiratorial commentators believe that Yanukovych rejected the agreement at the insistence of Russian president Vladimir Putin, a more plausible explanation is that Yanukovych hopes to avoid the kind of short-term disruption to Ukrainian industry that could result from opening Ukraine’s markets to European-wide competition just months before he hopes to win reelection in February 2015. Theres also plenty of blame for the European Union itself, which didn’t go out of its way to make the path for Ukraine incredibly easy, in light of Ukraine’s longstanding relationship with Russia.

But too much of the international media’s coverage attempts to frame the Ukrainian protests as some kind of ‘Orange Revolution’ redux, with Western media almost gleefully urging Yanukovych’s overthrow by mob acclamation.

It’s true that Yanukovych is relatively pro-Russian and many of his opponents are relatively pro-Western, and it’s very true that Yanukovych’s record is littered with authoritarianism and corruption. But that interpretation both overstates the differences among the Ukrainian political elite (when hasn’t Ukraine been relatively corrupt?) and it understates the massive economic, demographic and social problems that Ukraine has faced since the end of the Cold War. The much-hyped Orange Revolution didn’t settle the question of Ukraine’s relative identity vis-à-vis Russia and the West, and the current round of protests won’t likely settle the question either.

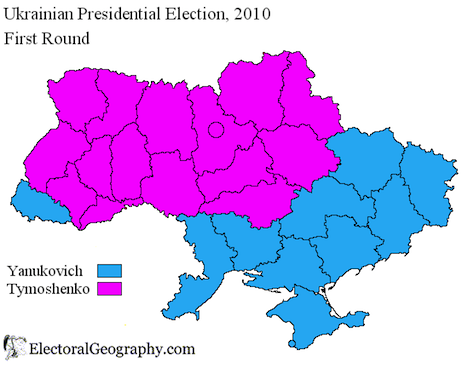

Here’s a look at the map of the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election results, which pitted Yanukovych against the relatively pro-Western Yulia Tymoshenko, a former prime minister who is now jailed on what many agree to be politically motivated charges:

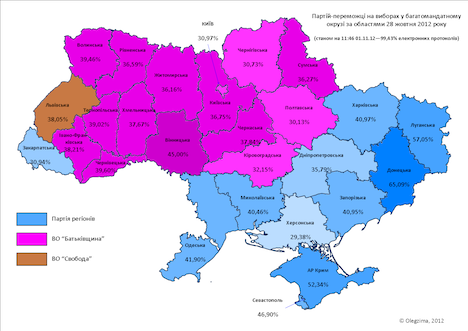

Here’s a look at last October’s parliamentary election results — blue represents Yanukovych’s governing party, the Party of Regions (Партія регіонів), and pink represents Tymoshenko’s party, the center-right ‘All Ukrainian Union — Fatherland’ party (Всеукраїнське об’єднання “Батьківщина), which emerged as the largest opposition party:

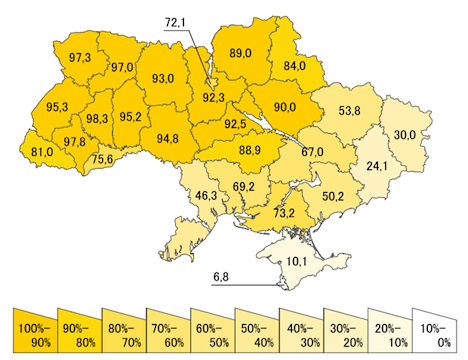

Now here’s a map of Ukraine’s regions that shows the percentage of the regional population that speaks Ukrainian (rather than Russian):

Notice any similarities?

You should — the lesson here is that Ukraine is split between a western Ukrainian-speaking population and an eastern Russian-speaking population that’s divided not only by language, but by cultural, political and economic differences.

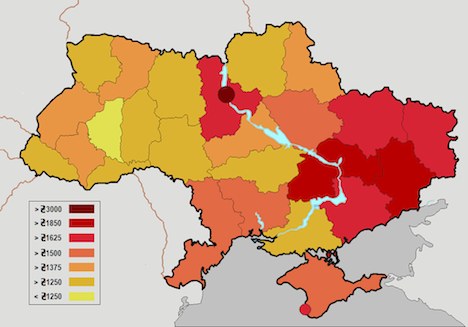

Here’s a look at average salary by region, for example, which shows that the Russian-speaking east, where many of Ukraine’s major cities are located, is economically stronger than the Ukrainian-speaking west, except the region surrounding Ukraine’s capital Kiev (and, to a lesser degree, the region surrounding Odessa on the Black Sea coast, where tourism boosts the local economy):

It’s difficult to overstate the differences between the ‘two Ukraines.’

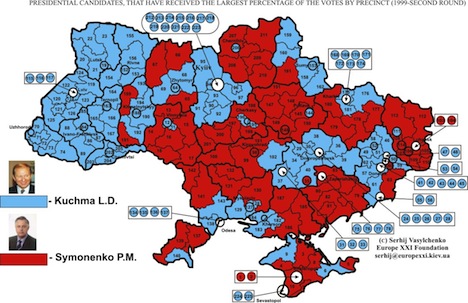

If anything, the most permanent effect of the 2004 presidential crisis and the ‘Orange Revolution’ was to arrange post-Kuchma Ukrainian politics along now-familiar regional and linguistic lines, which have already outlasted any tangible legacy of the Yushchenko era. Perhaps one of the few reasons to applaud the stewardship of Ukraine’s post-Soviet president Leonid Kuchma is for his ability to fashion a national civic identity in the post-Soviet era. Here’s a map of the 1999 presidential election:

Though the ‘Orange Revolution’ managed to install Viktor Yushchenko as president after the rerun of the second round of Ukraine’s presidential election in December 2004, it was hardly the massive victory for Ukraine’s ‘pro-European’ forces. Even with much of the world’s media rooting for him after an alleged dioxin attack nearly killed him, Yushchenko managed just 51.99% of the vote to 44.20% for Yushchenko. Yes, that vote broke down on the same reliable lines of the three maps above:

But it didn’t take Yushchenko very long to lose the enthusiasm of his Orange revolutionaries. The economy’s post-Soviet expansion, combined with the turmoil of late 2004, sent Ukraine’s economy tumbling from around 12% GDP growth in 2004 to less than 3% in 2005. Cracks also appeared along the once-united Orange Revolution front, especially between Yushchenko and his prime minister, Tymoshenko. A high-profile dispute with Russia in January 2006 ended with Russia’s temporary decision to cut off the supply of natural gas to Ukraine, deeply damaging Yushchenko’s government by demonstrating Ukraine’s deep reliance on Russia for its energy needs.

So it was no surprise when Yushchenko’s party finished third in the March 2006 parliamentary elections, behind both Yanukovych’s Party of Regions and Tymoshenko’s party. Barely a year after his ignominious loss in the Ukrainian presidential election, Yanukovych became Ukraine’s prime minister, establishing a difficult power-sharing arrangement in Kiev that slowed much of the momentum for reform (if it ever really existed at all).

A new round of parliamentary elections in September 2007 were equally inconclusive, though the pro-Western Tymoshenko emerged as the new Ukrainian prime minister. But Tymoshenko, preparing for her own 2010 presidential run, ultimately became more foe than friend to Yushchenko, whose popularity sunk to single digits. The next two years featured the grim aftermath of the global financial crisis and grueling rounds of negotiation with Russia over the supply of natural gas to Ukraine. Tymoshenko’s distancing wasn’t enough to salvage her own presidential hopes, and she lost a very narrow runoff contest in February 2010, with Yanukovych winning 48.95% to Tymoshekno’s 45.47%.

There are certainly reasons to doubt Yanukovych’s dedication to building democratic institutions in Ukraine — chief among those doubts is the way in which his government abruptly arrested, convicted and jailed Tymoshenko shortly after the last presidential election. Ridiculously, Tymoshenko’s ‘crime’ was abuse of office — she was charged with criminal culpability for negotiating, as Ukraine’s relatively pro-Western prime minister, a natural gas pipeline deal with Russia that was too pro-Russian. At the time Tymoshenko signed the 2009 gas agreement, Russia had impeded the gas flows for 13 days to Ukraine (and much of southeastern Europe), so Tymoshenko was negotiating the deal under duress. Notably, Yanukovych hasn’t tried to renegotiate the deal as president. In April, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Tymoshenko’s imprisonment was unlawful, and the incident continues to sour EU-Ukrainian relations.

There are also doubts about last year’s elections after Yanukovych changed how the 450 members of Ukraine’s unicameral parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, are elected. He revised Ukrainian electoral law — instead of determining all 450 members on a purely proportional representation basis, the October 2012 elections were determined on a split basis. Half of Ukraine’s legislators were elected by proportional representation and half of Ukraine’s legislators were elected in single-member districts. In effect, the electoral law changes rewarded Yanukovych’s party with relatively more seats, because Tymoshenko’s Fatherland split much of the opposition vote with the new Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform (Український демократичний альянс за реформи), formed by heavyweight boxing champion Vitaliy Klychko.

Yanukovych’s Party of Regions won just 72 seats by proportional representation (Fatherland won 62 and UDAR won 34), but it won 113 seats through the first-past-the-post districts (Fatherland won 39 and UDAR just six) on the basis of splitting the opposition vote.

That election has left Yanukovych and his prime minister, Mykola Azarov, with a relatively stable grasp on power, and the parliamentary majority that the Party of Regions enjoys means that it’s very unlikely that protestors will budge Yanukovych from office (though Yanukovych may yet offer up Azarov’s resignation to quell the fury). But that stability comes in spite of signs that Ukrainians are unhappy with the economy and their government, most notably the widespread corruption that flows from the highest levels of public office. The economy barely registered growth in 2012 (0.2%), and it’s estimated to mark zero growth again this year, with global demand for Ukrainian steel exports relatively slack. That’s in addition to the more structural difficulty of a population in decline. Ukrainian population peaked at around 52 million two decades ago, and it’s been steadily declining to just around 45.5 million today, representing the loss of one-eighth of Ukraine’s population in 20 years.

Since at least May 2013, Klychko has been gaining ground of Yanukovych in advance of the 2015 presidential election — in one poll, Klychko and Yanukovych were tied with 16% each in first-round preferences (with Tymoshenko trailing at 9%), and Klychko led Yanukovych by a wide 38%-19% margin in runoff preferences. Rumors abound, however, that Yanukovych could try to force through restrictive election requirements that would prevent Klychko from running on the basis of the income Klychko earned as a boxer in Germany.

Even if the current wave of protest powers Klychko to the Ukrainian presidency in 2015, however, there’s no indication that Klychko can succeed where Yuschenko, Yanukovych and Tymoshenko have all failed in the past. The major rupture that awaits Ukraine isn’t another round of protests or another color of revolution, but the day in which its leaders agree to reforms that reduce rampant corruption, help reduce Ukrainian dependence on foreign energy, liberalize an economy that’s struggling to compete in a global economy and attempt to address the growing fiscal and demographic challenges of a population in decline.

The revolution will be televised !!!