In an election campaign with few twists and even fewer turns, leave it to a blast from Germany’s past to shake up politics just 12 days before Germans head to the polls.![]()

In a move that seems baffling at first glance, former chancellor Helmut Kohl spent the weekend welcoming Rainer Brüderle, a former economics and technology minister, and Philipp Rösler, the vice minister for economics and vice chancellor, and the leader of the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), to his home — and indicating that he was all but endorsing the FDP in elections later this month.

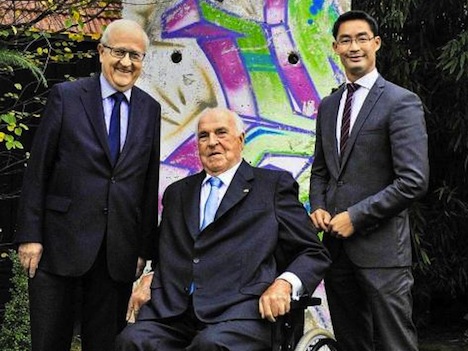

It’s odd for many reasons, not least of which because Kohl (pictured above, center, with Brüderle left and Rösler right), the longest-serving chancellor since Otto von Bismark, was the longtime leader of the center-right Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union) that chancellor Angela Merkel now leads. Kohl, now age 83, has been out of frontline politics since 1998, when he lost his bid for reelection. Among Kohl’s top accomplishments are vital roles in engineering both the reunification of West and East Germany and the development of the European single currency.

So what is Kohl up to?

There are a handful of reasons why Kohl might be campaigning so openly for the Free Democrats in the last stretch of the campaign, but none are as compelling as the explanation that Kohl is actually doing Merkel and the CDU a huge favor by boosting their coalition partners.

The Free Democrats are the junior partners in Merkel’s governing ‘black-yellow’ coalition, and though Merkel would prefer to continue governing alongside the Free Democrats, their support has dropped so low that it risks missing the 5% threshold necessary to win seats in the Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament. With the Christian Democrats holding a consistent double-digit lead over the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, the Social Democratic Party), and with voters preferring Merkel with a two-to-one margin over Social Democratic chancellor candidate Peer Steinbrück, there’s not much risk that the CDU will lose on September 22 — together with its Bavaria sister party, the Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, the Christian Social Union).

So if Kohl can bring a few crossover voters from the CDU to support the FDP, he can help guarantee that the Free Democrats make it back into the Bundestag with at least a minimum of seats, therefore facilitating the possibility that Merkel can continue her preferred coalition in a third term without resorting to a grand coalition with the Social Democrats (as she did from 2005 to 2009). Crazy like a fox.

It’s a dangerous game, though, because there is some risk in that strategy. Steinbrück delivered a strong performance in last week’s debate with Merkel and while it hasn’t helped him in the polls so far, the race could tighten in the closing days. Moreover, the newly formed Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany), the country’s first eurosceptic party could steal votes from Merkel on the right, and it’s the one party that’s gaining in polls over the past week — it could even hit the 5% threshold to enter the Bundestag. But at this point, with less than two weeks to go, a massive change would require a year’s worth of stubborn German public opinion to transform virtually overnight. So it’s a risk that Kohl — and likely even the cautious Merkel — are probably happy to take.

It’s also important to remember that Kohl and Brüderle are close, and they share political origins in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate in the southwest of Germany — Kohl served as minister-president of the state in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and Brüderle got his start as the state’s economics minister from 1987 to 1998 before moving into federal politics.

Also, with German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble in the news recently discussing the possibility of a third European bailout for Greece after the German election, you might also look at Kohl’s support for the FDP as a slight tweak to Schäuble, Kohl’s one-time-mentor who became an increasingly disappointed rival as Kohl refused to cede the chancellorship to him in the 1990s. In an interview last weekend while meeting with Brüderle and Rösler, Kohl argued that Greece never should have been in the eurozone to begin with — and though he laid the blame with his successor, SPD chancellor Gerhard Schröder, it’s hard not to read some mild criticism of Schäble’s European and economic policy in Kohl’s remarks, given that hostility between the two even today.

Photo credit to Reuters.

One thought on “What is Helmut Kohl thinking by endorsing the FDP in Germany’s elections?”