Even before the United States has provided any public evidence that Syrian president Bashar al-Assad is responsible for what appears to be a craven chemical warfare attack in Ghouta last Wednesday, the United States is preparing to launch missile strikes against Syria and Assad in retaliation as soon as Thursday, with the support of French president François Hollande and British prime minister David Cameron.![]()

![]()

![]()

That marks a failure of U.S. president Barack Obama’s foreign policy in at least four senses.

The first is that we still don’t know what happened last Wednesday. We do know that a chemical attack of some variety ultimately killed many civilians, up to 1300, on the eastern outskirts of Damascus. But we don’t know which chemical agent caused it (was it sarin? was it concentrated tear gas? was it mustard or chlorine gas?) and, more importantly, we certainly don’t know who launched the attack. While the U.S., French and British governments assure us that Assad was responsible, the public evidence is far from certain. While the U.S. state department claims that a full intelligence assessment is coming later this week, it assures us for now that it’s ‘crystal clear’ that Assad is responsible. But how credible will that assessment be if it’s delivered hours or minutes before a U.S. military strike? If it’s delivered after the military strike? Will it contain forensics evidence gathered yesterday by United Nations experts? No one knows.

While Assad’s certainly a prime suspect, there’s more than enough reason to believe, in the absence of further intelligence or forensic evidence to the contrary, that anti-Assad rebels could well have perpetrated the attack to frame Assad and draw the international community (or at least the United States and Europe) into the kind of response that now seems likely to happen in the next 48 hours. At a minimum, the United States should wait for U.N. chemical weapons inspectors, who spent at least a short time on the scene of the attack yesterday, to draw what conclusions they can on the basis of hard evidence. What happens if we learn in one year or five years that radical Sunni elements within the opposition were responsible for the attack? That will only encourage false-flag attacks in the future designed to provoke the United States into inadvertently taking sides in a civil war.

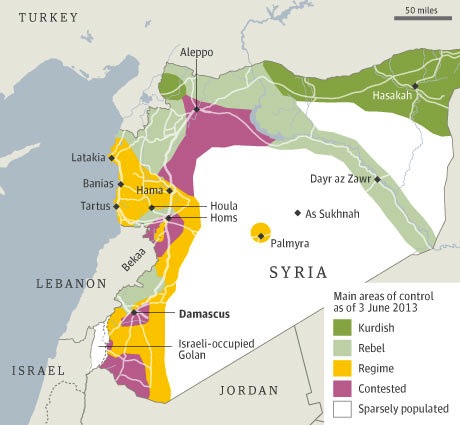

The second is that it’s an uncharacteristically unilateral, hasty and severe response. Assume that we had proof that Assad is responsible for the chemical attacks. The next step would be to determine the appropriate response from the international community, and it is telling that the United States and its British and French allies believe that a military response should be the first step, not the last step. There’s a panoply of various responses that the United States is ready to bypass, all of which could bear the stamp of legitimacy of the United Nations Security Council. Those include a U.N. peacekeeping and/or further inspections forces, a NATO-led and UN-approved no-fly zone, a tighter regime of diplomatic and economic sanctions against the Assad regime, and a prosecution against Assad and his military leaders for crimes against humanity in the International Criminal Court. Moreover, given the current stalemate, Syria is now essentially split into three disparate parts: pro-Assad territory along the coast and the Lebanese border, anti-Assad territory in the north and Kurdish strongholds in the northeast:

With Assad regaining ground over the past months, it doesn’t look like the end of the civil war will come from a military triumph but from a political settlement. That makes an immediate military response (and not a political response) from the United States even more inappropriate. By all means, use the threat of military action as a negotiating point with Russia and Syria’s other allies on the Security Council. But by launching a hasty attack just eight days after the incident makes it seem to the rest of the world that the U.S. action is less concerned about punishment for chemical warfare, but rather salvaging the credibility of the Obama administration over an ill-advised ‘red line’ stand that Obama articulated last autumn in the heat of a presidential campaign.

The third is that three days of military strikes from a U.S. warship in the eastern Mediterranean are very unlikely to cause any lasting damage to the Assad regime. Unlike a potential no-fly zone or a legitimate peacekeeping force, ‘phoning it in’ with a handful of missiles is likely to accomplish exactly nothing. It is unlikely that the United States can destroy the Assad regime’s capability to launch chemical weapons attacks in the future (if indeed the Assad regime is responsible) let alone destroy the stockpiles of chemical weapons that exist in Syria. After the U.S. strikes end, Assad and his allies will soldier on, but they will now be able to wrap their bloody war in the cloak of anti-Americanism.

Which leads to the fourth — and most troubling — failure. While the United States (and the international community as a whole) has an important security interest in maintaining the taboo against the use of weapons of mass destruction, it also has an equally important security interest in the notion that Syria’s conflict doesn’t become even more internationalized than it already is. Border skirmishes and Kurdish refugees into Turkey long ago ruptured the relationship between Assad and Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who seems likely to support the U.S. effort (despite his displeasure with the muted U.S. and European response to the Egyptian military coup that toppled Erdoğan’s Islamist ally Mohammed Morsi in Egypt last month).

Sectarian violence in Syria between pro-Assad Shi’a/Alawite and anti-Assad Sunni may also exacerbate ongoing Sunni/Shi’a tensions in Iraq, which continue to simmer even after their peak in 2005-07. The threat is greatest in neighboring Lebanon, where Hezbollah, the Shiite political organization and militia, has boldly stepped up its support for Assad, and radical Sunni groups in Lebanon are now openly supporting anti-Assad groups, despite pleas from the broader Lebanese political spectrum to remain neutral. U.S. intervention could also torpedo the chances of rapprochement with Iran’s newly inaugurated, more moderate president Hassan Rowhani, and it could also detract attention from the possibility of progress in the latest round of Israel-Palestinian peace talks.

Photo credit to Dieter Nagl/AFP/Getty Images. Graphic credit to The Guardian.

5 thoughts on “On Syria, Obama administration prepared to shoot now, ask questions later”