As widely expected, Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) surged to an overwhelming victory in Sunday’s national elections in Japan to determine half of the seats (121) in the House of Councillors, the upper house of the Diet (国会). While the victory wasn’t enough to give the LDP a two-thirds supermajority in both houses of the Diet, it was enough to usher in a new era of continuity, with the government of prime minister Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) set to consolidate power after winning election in the lower house, the House of Representatives, last December.![]()

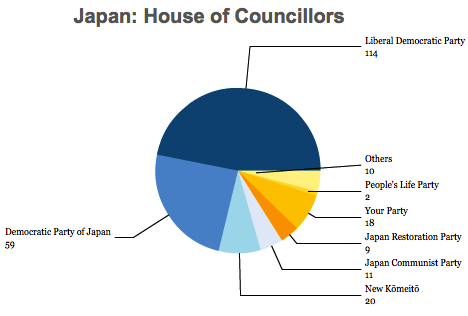

The result leaves the LDP, together with its ally, the Buddhist conservative New Kōmeitō (公明党, Shin Kōmeitō) with a majority in the upper house, and that will give the LDP the ability to push through legislation without needing to compromise in the House of Councillors and it makes Abe the strongest Japanese prime minister since Junichiro Koizumi (小泉 純一郎) in the early 2000s and ends a seven-month period of a ‘twisted Diet,’ with control of the upper house still in the hands of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō).

But the LDP looked set to fall just below an absolute majority in its own right:

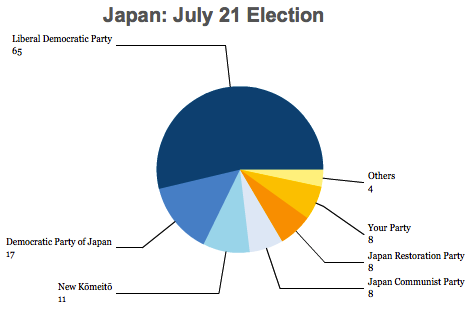

In contrast, the LDP holds 294 seats in the 480-seat House of Representatives, and together with the 31 seats of New Kōmeitō, holds a two-thirds majority. That the LDP doesn’t hold an equally impressive advantage in the upper house is due to the fact that only half of the seats in the House of Councillors were up for election yesterday and, among those 121 seats, the LDP’s dominance is clear:

That also means that the Democratic Party doesn’t face an immediate wipeout, and it will remain the chief opposition party — in fact, their 59 seats in the House of Councillors is actually more than the 57 seats they currently hold in the House of Representatives. That will give the DPJ a legislative base from which it can attempt to rebuild itself as a political force and to position itself for 2016, when Japan’s next elections are likely to come. Banri Kaieda, a fiscal hawk who assumed the party’s leadership after its December 2012 defeat, will stay on for now as leader.

But the Democrats weren’t the only losers on Saturday. It was perhaps an even more difficult election for the Japan Restoration Party (日本維新の会, Nippon Ishin no Kai). A merger between the two smaller parties of Osaka mayor Tōru Hashimoto (橋下徹) and right-wing, nationalist former Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara (石原慎太郎), it emerged with 54 seats in the House of Representatives in December to become as the third-largest party. But it won just eight seats on Saturday, and the party now seems likely to split up. That’s largely due to Hashimoto’s awkward comments suggesting U.S. soldiers in Okinawa should be permitted to use prostitutes and controversial comments that largely defended the ‘comfort women’ system, whereby Japanese soldiers forced women in enemy countries to serve as sexual slaves. But it’s also due to the fact that nationalist tensions stemming from a standoff with the People’s Republic of China over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese) have calmed somewhat since last December.

One success story was the Japanese Communist Party (JCP, or 日本共産党, Nihon Kyōsan-tō), which won eight seats on Saturday, bringing its total to 11. Founded in 1922, the JCP has not been a strong force in recent years. Though it has left its Marxist roots in the past, it has gained a modest amount of strength since the 2008 global financial crisis and it supports ending Japan’s military alliance with the United States.

But beyond the horse-race dynamics of Saturday’s result, what can we expect from Japanese policy in the next three years? Here’s a look at eight key issues that are likely to dominate the LDP’s agenda, at least in the near future.

Japan’s political structure. After the Democratic Party’s breakthrough victory in 2009, commentators both inside and outside Japan trumpeted the emergence of a true two-party system, after essentially the dominance of the LDP since its inception in 1955. But that account was always a little too simplistic, given that Japan always featured spirited political competition within the various LDP factions. Despite the fact that the LDP’s factions have been on their best behavior since Abe regained the party presidency in summer 2012 and thereupon returned to government last December, it seems certain that discipline will falter before 2016. Given that the Democratic Party seems destined for a period of introspection and rebuilding, and given that the Japan Restoration Party may disintegrate within days, the reemergence of the LDP’s factions may not necessarily be a bad thing — with the return of LDP hegemony, factions will serve as the most robust checks and balances to the Abe government. Though Abe is riding high today, Japanese government are notoriously short-lived (since 2006, the average length of a government has been just 380 days), and the biggest threat to Abe will be that he’ll be toppled from within the LDP if his popularity flags.

Bottom line: While the LDP is virtually guaranteed to remain in power until 2016, Abe is not. The LDP’s various factions are still strong enough to hold Abe’s government accountable.

Abenomics. The first two ‘arrows’ of Abe’s economic program — what’s become popularly known as ‘Abenomics’ — have proven predictably popular. Those policies included a massive ¥10.3 trillion ($116 billion) spending program designed to stimulate Japan’s economy and a push to reorient the Bank of Japan toward looser monetary policy, including a push for quantitative easing and an explicit target of 2% inflation for the next two years, with the appointment of a new BoJ governor, Harhuiko Kuroda (黒田 東彦), in March. If Abe has a mandate from the weekend’s election, it’s in favor of his dual push for greater fiscal and monetary stimulus, and it’s easy to understand why spending on public works projects has been relatively popular across all the LDP’s factions. But the challenge for Abe will be to know when to prioritize the issue of Japan’s long-term fiscal imbalance, which has led to a public debt of around 240% of GDP. A premature push toward fiscal consolidation, after over two lost decades of economic stagnation, could jeopardize the Japanese economy’s tentative gains — for example, the Nikkei has surged by over 60% and the yen has lost about 25% of its value (thereby boosting Japanese exports by making them less expensive), since last November when the full extent of ‘Abenomics’ came into relief, and the Japanese economy grew at an annualized rate of around 4% in the first quarter of 2013. The biggest threat to Abe is anything (including an increase in the consumption tax) that could reverse those fragile trends.

Bottom line: Abenomics has proven the most popular economic policy in over a decade, but it will have to start delivering economic growth well before 2016.

Structural reforms. It’s difficult to know whether the third ‘arrow’ of Abenomics will ever hit its target. Despite a wan pre-election outline of structural reform in June, Abe’s victory will give him the best shot to push forward with even more radical reforms to boost Japanese economic growth, largely through deregulation, labor market liberalization, and possibly a revamp of Japanese corporate governance. The extent of his success will be an early test of Abe’s ability to maintain the discipline of the LDP’s factions. Deregulation, for example, could face significant resistance from highly protectionist elements within the LDP, none so strong as Japan’s entrenched agricultural interests. Moreover, it’s obviously a lot easier to pass legislation to spend money on new projects than for reforms that make it easier to fire workers, but Abe’s mandate is so strong that he will have a good chance at pushing through at least some reforms in the months ahead. Other more ambitious reforms could include the privatization of Japan’s water and electricity utilities, though recent precedent shows that could be difficult — even the massively popular Koizumi faced significant resistance to his keystone 2005 achievement of privatizing Japan Post, a postal savings behemoth that had essentially become the country’s largest bank.

Bottom line: Expect some tangible reforms from the Abe government — and fairly soon, but the extent of those reforms is the biggest unknown looking forward.

Consumption tax. The hazy fourth arrow of Abenomics could be fired as soon as October, when the government will review the prior DPJ government’s decision to double the consumption tax from 5% to 10%, which was originally supposed to take effect in 2014. Whether the Abe government pushes forward with it will depend upon its reasoned consideration of whether Japan’s economy has sufficiently improved to warrant measures that would start to bring Japan’s finances into greater balance.

Bottom line: It wouldn’t be surprising to see Abe confirm the consumption tax increase sooner rather than later, but it would also be surprising if the consumption tax will begin to take effect next year. A significant delay is more likely.

Nuclear energy. The LDP stands alone as the only political party that doesn’t support the elimination of nuclear energy. But that doesn’t mean that its victory should be read as a mandate for a renewed push to restore Japan’s nuclear energy capacity just two years after the massive Fukushima meltdown. Furthermore, two factors will stand in the way of any renewed LDP push to bring Japan’s nuclear reactors back online (48 out of 50 are still idled following the Fukushima incident). The first is simple political arithmetic — because the LDP enjoys a majority in the House of Councillors only with New Kōmeitō, which is opposed to nuclear energy, it will still be hard to pass any pro-nuclear legislation through the Diet. The second is that the power to determine when to restart Japan’s reactors no longer lies in the power of the government, but with the Nuclear Regulation Authority that the previous DPJ administration established in September 2012.

Bottom line: Abe’s hands are tied with respect to the most pressing decisions on nuclear energy, and he doesn’t have enough strength in the House of Councillors to push for pro-nuclear legislation.

Article 9. Though he had not emphasized it in the early months of his government, Abe has made it increasingly clear in the days leading up to Sunday’s election that he wants to push forward with a potentially controversial amendment to Japan’s famously pacifist constitution — in particular, Article 9, which prohibits Japan from having a conventional military. Instead, Japan currently has Self-Defense Forces, though Abe has long wanted to change that in order to permit Japan to become an ‘ordinary country.’ Abe, whose first term as prime minister seven years ago was marked by an emphasis on Japanese nationalism, has long favored revising Japan’s constitution to permit it to join routine peacekeeping forces and to facilitate Japan’s ability to defend itself within East Asia, especially with regard to North Korea. Abe will win support from other parties, such as the Japan Restoration Party and the urban-based Your Party (みんなの党, Minna no Tō), but because its governing ally New Kōmeitō leans toward a more pacifist vision, and because constitutional amendments require a two-thirds majority, Abe seems likely to be thwarted. Supporters, too, are worried that, free from the constraints of having to win an election anytime soon, Abe will turn his focus to Article 9 at the expense of carrying through economic reforms. Abe tried to allay those fears after the election by reaffirming his commitment to the primacy of Abenomics, adding that he’s not necessarily in a hurry to amend Japan’s constitution.

Bottom line: It’s hard to see how Abe gets to a two-thirds majority to amend Japan’s constitution, given Sunday’s election result. For all the smoke about Abe’s nationalism, it will be hard for Abe to do anything without convincing the LDP’s pacifist ally New Kōmeitō to support an amendment.

Trans-Pacific Partnership. Abe indicated in March that he hoped to bring Japan into the widening negotiations of the Trans-Pacific Partnership among the United States and other countries in southeast Asia and South America. But the same forces within the LDP that might prove to be obstacles to structural economic reform, especially with respect to agricultural policy. If Abe actually succeeds in opening Japan’s agricultural market to the United States, it would be a huge triumph.

Bottom line: Even if Abe brings Japan into the TPP negotiations and even if Abe succeeds with enacting ‘third arrow’ reforms, it’s still unlikely that Japan’s agricultural interests will agree to liberalize Japan’s markets anytime soon.

Regional relations. Managing sometimes tricky relations with Beijing and Seoul need not be a difficult task — it would help if politicians like Hashimoto would stop making inappropriate remarks defending ‘comfort women’ and reopening the old wounds of World War II. Abe has a chance to take a higher road on August 15, the anniversary of Japan’s defeat in the war, by not visiting the Yasukuni Shrine to the Japanese war dead (including several war criminals), which would unnecessarily inflame relations with Japan’s neighbors. Like Abe, both South Korean president Park Geun-hye and Chinese president Xi Jinping are just in their first year in office, and both Park and Xi are warily waiting to see how Abe will behave now that he no longer has to answer to the Japanese electorate. Although Abe’s push to revise Article 9 need not be inflammatory, so long as Abe keeps his South Korean and Chinese counterparts informed of his plans, Abe’s nationalist tendencies indicate he might take a more muscular position. (Nobusuke Kishi, Abe’s grandfather, was a wartime minister who was arrested on suspicion of war crimes after Japan’s 1945 surrender, though he was never convicted and ultimately became prime minister). But China will soon boast the world’s largest economy, so Abe might be better served to prioritize improving Japan’s image on the Chinese mainland — in the wake of the Senkaku dispute, many Chinese residents refuse to buy anything Japanese. Japan’s access to the vital Chinese market is much more important for Japan’s future than short-term grandstanding for a nationalist audience or even the amendment of Japan’s constitution, but it’s not immediately clear that Abe sees the world that way.

Bottom line: It’s unclear whether Abe will try to repeat the kind of nationalist bluster that marked his first term as prime minister, but Japan’s clear long-term interests are to develop closer cultural and economic ties with China and South Korea, not to alienate them over gaffes, slights over World War II and minor border disputes.

One thought on “Quivering for the fourth arrow of Abenomics (and other Japanese policy matters)”