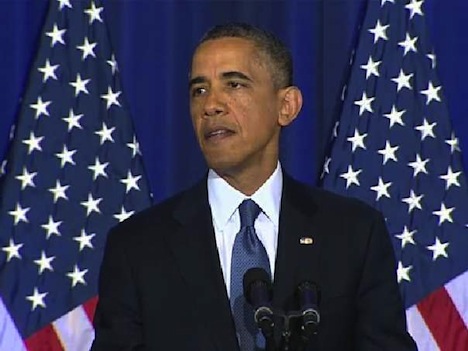

There’s a lot to unpack from the wide-ranging speech that U.S. president Barack Obama gave this afternoon on the United States and its ongoing military action to combat terror organizations.![]()

I got the sense that Obama’s been anxious to make this speech for some time and to make the terms of debate over targeted attacks from unmanned aircraft — ‘drones’ — public. The speech itself came after U.S. attorney general Eric Holder admitted in a letter for the first time that U.S. drones killed Anwar al-Awlaki in Yemen, as well as three other U.S. citizens accidentally. It’s important to recall, furthermore, that Obama only first publicly acknowledged the drone strikes in Pakistan last year during an online chat.

It’s far beyond my blog’s realm to delve far into the speech in specificity — Benjamin Wittes has already done that in a series of blog posts (here and here) at Lawfare that are more articulate than anything I could produce in such a short time frame. But when the president of the United States delivers a wide-ranging address on the U.S. war on terror, it has so many effects on world politics that it’s impossible not to think about how policy may change in the remaining years of the Obama administration.

Those policy decisions are incredibly relevant to international law and politics, but also in the domestic politics of two dozen countries — Pakistan, Yemen, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and so on.

What I do have, however, are a lot of questions that remain following the speech — perhaps even more than I had before I watched the speech.

- Associated forces. Obama mentioned al-Qaeda’s ‘associated forces’ four times, but what exactly is an associated force? The lack of any meaningful definition lingered awkwardly with every mention. In many ways, this goes to the heart of the legal issue with the drone strikes in places like Yemen and Somalia, and whether they’re even authorized under the Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF). Al-Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula (AQAP) and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) share a name, and key links, but it’s really difficult for me to believe that impoverished radical Yemenis or Tuaregs are really so associated with the original iteration of al-Qaeda that Osama bin Laden led in 2001. Somalia’s al-Shabab is often described as a home-grown al-Qaeda, but is it an associated person? It’s even more doubtful than AQAP and AQIM. Hamas and al-Qaeda are certainly mutually sympathetic and may well have mutual ties over the past two decades, but does that make Hamas an associated force? In the same way, the Taliban in Afghanistan is not affiliated with the Tehrek-e-Taliban Pakistan (i.e., the Pakistani Taliban), but they’ve been a particular target of the Obama administration’s drone strikes in Pakistan — so much so that drone strikes were a top issue in Pakistan’s recent national elections. So there’s a real question as to whether those actions legal — if those targets aren’t associated forces, the targets aren’t subject to the use of military force under the AUMF.

- The precision of future drone strikes. Obama has committed to more judicial use of drone strikes that have, as Obama admitted, killed civilians in the past, and though he didn’t exactly outline it in his speech, it’s reported that the U.S. military will take over some of the role that the Central Intelligence Agency has played in the drone strikes in recent years. Nonetheless, the CIA has been reported to have used so-called ‘signature strikes,’ which target young men who live in areas known to be dominated by radical terrorist groups, though the strikes aren’t based on specific identification or intelligence that ties the targets to clear engagement against the United States. Obama didn’t mention ‘signature strikes’ today. But he argued that the use of drones is ‘heavily constrained’ and further bound ‘by consultations with partners’ and ‘respect for state sovereignty,’ and that drone strikes are only waged against terrorists ‘who pose a continuing and imminent threat’ when there are not other governments ‘capable of addressing’ that threat,’ and only when there’s a ‘near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured.’ That’s a much higher standard than what’s been reported in the past. So was Obama describing past policy on drone strikes or future policy? What do assurances of more precision in the future mean when we don’t know the level of care with which the drone strikes have been effected in the past?

- The oversight of future drone strikes. It’s also unclear how the Obama administration believes oversight should be handled. Obama, in his speech, noted that he’s asked his administration to review proposals for extending oversight on drone strikes, and he outlined several options, including something similar to the FISA courts that authorize electronic surveillance of U.S. citizens in the fight against terrorism. But he’s in year five of his administration — shouldn’t this be something that his administration has already considered? Will his administration be able to enact a system in time for Obama’s successor? Will it even be based in statute so that it’s binding on future administrations? All of this is unclear. Continue reading Questions on the U.S. war on terror, Obama’s big speech and its effect on world politics