Last week, even before all of the votes had been counted, when it was clear that Nawaz Sharif would be Pakistan’s next prime minister, he named his designee for finance minister — Ishaq Dar (pictured above).![]()

Dar served as Sharif’s finance minister from 1998 until Sharif’s overthrow by army chief of staff Pervez Musharraf, and he spent much of his previous time as finance minister negotiating a loan package from the International Monetary Fund and dealing with the repercussions of economic sanctions imposed by the administration of U.S. president Bill Clinton on both India and Pakistan in retaliation for developing their nuclear arms programs.

Currently a member of Pakistan’s senate, Dar briefly joined a unity government as finance minister in 2008, though Dar and other Sharif allies quickly resigned over a constitutional dispute over Pakistan’s judiciary. The key point is that even across political boundaries, Dar is recognized as one of the most capable economics officials in Pakistan.

It was enough to send the Karachi Stock Exchange to a new high, and the KSE has continued to climb in subsequent days, marking a steady rally from around 13,360 last June to nearly 21,460 today. Investors are generally happy with the election result for three reasons:

- First, it marks a change from the incumbent Pakistan People’s Party (PPP, پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی), a party that has essentially drifted aimlessly in government for much of the past five years mired in fights with Pakistan’s supreme court and corruption scandals that affect Pakistan’s president Asif Ali Zardari in lieu of a concerted effort to improve Pakistan’s economy.

- Second, the election results will allow for a strong government dominated by Sharif’s party, the Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML-N, اکستان مسلم لیگ ن) instead of a weak and unstable coalition government.

- Finally, Sharif’s party is viewed as pro-business and Sharif himself, more than any other party leader during the campaign, emphasized that fixing the economy would be his top priority. Sharif, who served as prime minister from 1990 to 1993 and again from 1997 to 1999, is already well-known for his attempts to reform Pakistan’s economy in his first term.

Sharif will need as much goodwill as he can, because the grim reality is that Pakistan is in trouble — and more than just its crumbling train infrastructure (though if you haven’t read it, Declan Walsh’s tour de force in The New York Times last weekend is a must-read journey by train through Pakistan and its economic woes). The past four years have marked sluggish GDP growth — between 3.0% and 3.7% — that’s hardly consistent with an expanding developing economy. In contrast, Pakistani officials estimate that the economy needs more like sustained 7% growth in order to deliver the kind of rise in living standards or a reduction in poverty or unemployment that could transform Pakistan into a higher-income nation. Already this year, Pakistan’s growth forecast has been cut from 4.2% to 3.5%.

The official unemployment rate is around 6%, but it’s clearly a much bigger problem, especially among youth — Pakistan’s median age is about 21 years old. That makes its population younger than the United States (median age of 37), the People’s Republic of China (35) or even Egypt (24), where restive youth propelled the 2011 demonstrations in Tahrir Square.

Although Pakistan’s poverty rates are lower than those in India and Bangladesh, they’re nothing to brag about — as of 2008, according to the World Bank, about 21% of Pakistan’s 176 million people lived on less than $1.25 per day, and fully 60% lived on less than $2 per day.

Though it has dropped considerably from its double-digit levels of the past few years (see below), inflation remains in excess of 5%, thereby wiping out much of the gains of the country’s anemic growth:

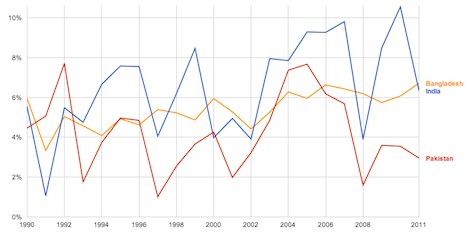

Pakistan is undeniably the ‘sick man’ of south Asia. India, even facing its own slump, has long since outpaced Pakistan over the past 20 years, and increasingly over the past decade, Bangladesh has consistently notched higher growth:

To make matters worse, Pakistan has a growing fiscal problem — although its public debt is lower than it used to be, it’s still over 60% of GDP, and a number of problems have led to debt-financed budgets in the past, including a 6.6% deficit in 2012.

That sets up a classic austerity-vs-growth conundrum for the Sharif government.

On the one hand, the familiar austerity hawks will argue that Sharif should focus on a reform program to lower Pakistan’s unsustainable deficits as a top priority. If, as expected, Sharif obtains a deal with the IMF for up to $5 million in additional financing to prevent a debt crisis later in 2013, the IMF could force Pakistan into a more aggressive debt reduction program than Sharif might otherwise prefer.

On the other hand, given the number of problems Pakistan faces, growth advocates will argue that Pakistan should focus on more pressing priorities and save budget-cutting for later. After all, with rolling blackouts plaguing the country, no one will invest in Pakistan regardless of the size of its debt. It’s also important to remember that Pakistan is not Europe — it’s an emerging economy with a young and growing population that could easily grow its way out of its debt problems in a way that seems impossible for a country like Italy or Greece.

So how exactly will Sharif and Dar attempt to fix Pakistan’s economy? Here are eight policies that Sharif’s government is either likely to implement — or should be implementing:

Get the lights back on. Power blackouts have plagued Pakistan for nearly a decade at this point, and despite a long list of economic woes, nothing has done more to slow Pakistan’s international competitiveness, productivity and output than a flickering power sector. There’s not one magic-bullet solution to the crisis, and in many ways, it’s a touchstone for all of the problems that Pakistan faces today. Sharif and his government shouldn’t be worried about spending whatever it takes to get Pakistan’s electricity working as a national matter in terms of public investment. They should also be willing to look into public-private partnerships and work with regional energy exporters, including Central Asian nations and Iran, if necessary. IMF analysts cluck about the waste of public funds on energy in Pakistan, and they’re right — government agencies routinely fail to pay for their electricity use, and subsidies have artificially raised demand for electricity and gasoline. Sharif should phase out those subsidies, informal and formal, for government and consumers alike. That revenue would be better spent on investments that can improve the reliability of Pakistan’s power grid.

Peace talks with the Pakistani Taliban. Neither the civilian government nor the military and security services in Pakistan can control parts of Pakistan’s remote northwestern frontier, and its control will remain weak so long as the region remains a hotbed of radical activity. When a government cannot meet its most basic of obligations to provide for personal safety, there’s little reason to believe that it is capable of securing other key ingredients for a stable economy, like property or contracts. Sharif has already signaled that he’s willing to negotiate with the Tehrek-e-Taliban Pakistan (i.e., Pakistani Taliban), and he’s already called for open talks with them, and that’s already an incredibly promising sign. While the Pakistani Taliban targeted the PPP and its allies throughout the campaign, it’s more open to Sharif, who in turn has always been more sympathetic to Islamists. Sharif alone can’t singlehandedly secure Pakistan’s frontier, and he’ll need some help from the United States, which is set to withdraw from Afghanistan later this year. Sharif should use his immediate political capital with the United States to achieve a moratorium on its repeated drone strikes while he conducts talks with the Pakistani Taliban, which in turn could lead to an even wider deal with the Taliban in post-occupation Afghanistan.

Work toward normalized trade relations with India. Despite the fact that it neighbors a market of over a billion consumers, Pakistan’s largest trade partners are the United States, China, the European Union and the United Arab Emirates. Pakistan sends nearly five times as many exports to Afghanistan (7% of total exports) than to India (1.3%). So greater foreign trade with India should be low-hanging fruit for Pakistan’s next government. Sharif has already indicated he’s willing to work toward warmer relations with India after decades of tension with foundations in the original 1947 Partition. Sharif, who was prime minister in the late 1990s when both India and Pakistan became nuclear-armed countries, is well-suited for this task, though many military leaders will remain anxious over Sharif’s peace overtures. As with his turn to the Pakistani Taliban, Sharif’s already made a solid first step by inviting Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh to his swearing-in. Sharif is likely to extend ‘most favored nation’ status to India, and although Pakistan’s agricultural and textile industries fear a sudden rush of competition, free trade could reduce the price of many everyday items for Pakistani consumers and allow for more technology imports to enhance Pakistan’s economic productivity.

Take real steps to end corruption. Sharif, already one of Pakistan’s richest businessmen, is unlikely to become as tangled in corruption as Zardari and the previous PPP government. But corruption has crippled the economy, and with more revenues now going to Pakistan’s provinces, there’s ever more opportunity for local officials to engage in skimming, bribery and other shenanigans. Although Sharif’s indicated he will try to reduce tax avoidance (see below), that’s just part of a wider problem. Pakistan’s courts have been particularly aggressive since the end of the Musharraf era — Pakistan’s supreme court has directly confronted Zardari and his government. Sharif should encourage judicial activism as well as greater transparency at all levels of government and tougher penalties for bribery.

Develop a cutting-edge mechanism for dealing with natural disasters. One of the most devastating drivers of Pakistani poverty over the past five years has been the 2010 and 2011 flooding that left nearly 20% of the country underwater. Although the world responded with massive relief aid, it wasn’t nearly sufficient. Corruption and incompetence meant that aid didn’t end up where it was most desperately needed. One of the highlights of Sharif’s first stint in power in the 1990s was massive spending on infrastructure, and it’s likely that he’ll be aggressive in his next term in power to boost Pakistan’s infrastructure, even beyond its power grid. He should spare no expense in developing a national agency tasked with dealing with natural disasters that can identify how to implement efficient relief programs to mitigate the human and economic trauma that result from floods and other shocks.

Focus on the entire country, not just Punjab. One of the most stinging criticisms of Sharif’s first two terms in government is that he focused on the improvement of his native Punjab province, where he derives much of his political support, at the expense of other provinces, including Sindh province, the PPP’s heartland. So while Sharif likes to brag that his previous government built Pakistan’s first superhighway, it’s a road that links Lahore, Pakistan’s second-largest city, to Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital. Both cities are located in Punjab, and one of the fears of a Sharif government is that he’ll govern Pakistan from a Punjab-first mentality. Moreover, in his first term as prime minister, his ‘National Economic Reconstruction Programme’ aggressively privatized industries that had been nationalized under in the 1970s. Though the nationalization and the liberalization policies helped boost GDP growth in the early 1990s, Sharif faced criticism that the process for selling off state-owned assets wasn’t incredibly competitive. Sharif needs to transcend those mistakes this time around — he can’t be a truly successful prime minister by diverting national largesse solely to Punjab and incidental benefits to Punjabi elites.

Collect more revenues. As noted above, Pakistan’s revenues amount to less than 10% of GDP, and tax collection rates are low, especially within agriculture, which represents over one-fifth of Pakistan’s economy. Dar, in particular, is keen on changing that. Last year, he and the PML-N backed a proposal to implement a tax on the agricultural sector, a position that would put Sharif at odds with many of his top supporters in Punjab. A carrots-and-sticks campaign to reduce tax avoidance would also help boost revenues. It’s a good first test for Sharif’s government because it will show that Sharif is serious about fiscal discipline, reducing corruption and, above all, governing in the best interests of Pakistan (and not just the best interests of Punjab).

Education, education, education. One of every two Pakistanis is under age 20. That means that Pakistan’s government needs to be serious about developing the skills of what could turn out to be the country’s most valuable resource of all — its labor force. Again, given a choice between widespread spending (even debt-financed spending) on jobs skills and training or more rapid budget consolidation, this seems like a no-brainer, especially in light of how little Pakistan currently spends on education. Pakistan’s literacy rate hovers at just around 55%, which is too low, both in absolute terms and in relative terms (it’s much lower than India’s rate of around 73%, for example). Despite real gains in education policy, no investment could yield more long-term dividends than to ensure that Pakistan’s wave generation has the skills sufficient to compete in a global economy. Even though unemployment remains a problem, a well-trained workforce is one of several factors that could lure back foreign investment to Pakistan. It’s the human-capital counterpart in delivering the kind of infrastructure that global companies want — and have recently found in greater abundance in India and Bangladesh.

3 thoughts on “Can Nawaz Sharif and Ishaq Dar fix Pakistan’s sclerotic economy?”