On Sunday and Monday, 1,517 eligible voters in the Falkland Islands (or, if you like, las Islas Malvinas) turned out to vote in the referendum on its status as an overseas territory of the United Kingdom.![]()

![]()

![]()

Fully 1,513 voters supported the current status, and three voters disagreed.

That should be an open-and-shut-case, right? Certainly under any principles of self-determination, a 99.74% victory for remaining under the aegis of the United Kingdom should be respected — the residents of the small islands that the United Kingdom (and the residents themselves) call the Falklands Islands and that Argentina call the Islas Malvinas, which lie just 310 miles off the coat of Argentine Patagonia (and over 8,000 miles from London).

Not so fast.

The dispute goes back to 1833 — and really, even further:

- To the 1520s, when Argentines claims that Ferdinand Magellan discovered them on behalf of Spain.

- To 1690, when the British say that captain John Strong first landed on the islands, naming them for Viscount Falkand.

- To 1764, when both sides agree that France settled Port Louis, though the Argentine and British stories vary as to what happened next — a British expedition certainly arrived in 1765 but had left, however, by 1774.

By 1833, the British were back — it’s essentially pretty clear that UK settlers took control of the islands in that year, and that those settlers and their descendants have remained there continuously ever since. But Argentina argues that it inherited the Spanish claim to the islands when it won independence. It’s unclear whether Argentina’s then-ruler, Juan Manuel de Rosas, in 1850, as part of the negotiations for the Arana-Southern Treaty between the United Kingdom and Argentina, conceded the claim to the British. Maybe he did. Maybe not. It’s not formally a part of the treaty.

Of course, settlers in North America rebelled against UK colonial rule to great effect — and independence — in 1776. But the claim here is different — and messier.

The UK-Argentine tussle only became more of an international tussle on Wednesday with the election of Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the archbishop of Buenos Aires as the new Catholic pope, Francis, who has asserted the Argentine claim to the islands. (For his part, monsignor Michael McMarcam the head of the Catholic Church on the islands, says the new pontiff is welcome in the Falklands/Malvinas).

Think of it this way: in a parallel world, imagine that the indigenous and Spanish settlers of Florida managed to withstand American invasion in the 1820s and form their own country. Within a decade, the United States (or, if you’d like, the United Kingdom) took control of the Florida Keys and, despite their proximity to Florida (remember, it’s not a U.S. state but rather a sovereign nation in our parallel universe), formed settlements. For generations, the US/UK and their Keys settlers and descendants held sufficient power to develop and deepen those settlements. Is it necessarily an easy case, even 180 years later? (Would your opinion change if you were Indian? Irish? Residents of Diego Garcia, the emptied British naval base in the Indian Ocean?)

The Argentine government argues that principles of self-determination don’t apply in the case of the Falklands/Malvinas, because the original generation of occupiers usurped the islands from Argentina, which was still in the growing pains of asserting its own independence. But that was 180 years ago, and generations of Falkands settlers have called the islands their home ever since. Is there a statute of limitations on such post-colonial claims?

For their part, Falklands settlers aren’t convinced:

I would like to know under what legislation the Argentine government calls it illegal. We approved it under our own laws here at the Falklands (Malvinas) and I was told that there is a meeting in the Argentine Congress on Wednesday to discuss its rejection. For a referendum that is illegal and for voters that don’t exist, they appear to be paying it a lot of attention.

The islands were the site of an infamous 1982 war between the United Kingdom (then under the leadership of prime minister Margaret Thatcher) and Argentina (then in the final years of Argentina’s last military junta that took power in 1976 and prosecuted the ‘Dirty War,’ in 1982 under the leadership of Leopoldo Galtieri). Galtieri ordered an invasion of the islands in April 1982 (the joke is after one bottle of whiskey too many), hoping that his newly confirmed cold warrior bona fides from U.S. president Ronald Reagan would forestall a military response from the United Kingdom.

Galtieri was wrong.

In April and May of 1982, Thatcher’s British naval forces re-took the islands, resulting in the death of over 250 British and over 650 Argentine soldiers. By June, Galtieri had resigned. By 1983, the longtime military junta withdrew from power in favor of the civilian leadership that’s run Argentina to this day, with the painful 1982 war viewed as a painful way for the junta to distract public attention from a crumbling economy and years of human rights abuses.

But if 1833 seems a long time ago, remember that Argentina’s declaration of independence from Spain occurred only in 1816, and it was only a couple years later that the nation actually concluded its war of independence with Spain. In contrast, by 1833, the United Kingdom was well into its age of empire and just four years from the coronation of Victoria, whose reign coincides with the peak of British empire.

It was also only at the end of the First Opium War in 1842 a few years later that the United Kingdom won its ‘lease’ of Hong Kong for 150 years, an overseas colony that it returned to the People’s Republic of China a decade and a half ago in 1997.

So the Argentine claim to the islands isn’t as farfetched as it may seem.

Before Thatcher’s little war in 1982, the British seems disposed to share sovereignty over the islands during the reign of Juan Perón in 1974, though the deal fell through when Perón died three weeks after a deal was allegedly reached. At least one British MP, the leftist George Gallaway, has argued that shared sovereignty is the way forward, though neither the British nor the Falklands/Malvinas residents seem inclined in the least to change the status quo.

The prize is more exciting than it may seem — though the islands already have a strong economy based on sheep farming, fishing and tourism, there’s the potential for oil exploration as well, with up to 120,000 barrels of petroleum per day by 2018 at stake. It’s not incredibly clear that the islands would necessarily deliver to Argentina a major boost to its GDP, though, as it perches precariously on the edge of a default in 2013, and it seems more likely than not that the Falklands/Malvinas are a useful issue to stir nationalist sentiment, as demonstrated in this plucky 2012 Olympics ad, which showed Argentine athlete Fernando Zylberberg provocatively training on the islands in advance of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London:

Argentina’s dismissal of the weekend referendum hasn’t dissuaded UK prime minister David Cameron, who has warned Argentina to back off:

Argentina can continue to posture. Intimidating fishing vessels. Claiming ownership of the Islands. Threatening businesses that trade with the Islands. Strangling the livelihoods of Islanders.

But as long as the Falklanders want to stay British, we will always be there to protect them.

His Argentine counterpart, president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, is just as adamant in opposition:

Speaking at an event at the Presidential Palace in Buenos Aires on Tuesday, President Kirchner said that “it’s as if a bunch of squatters were to vote on whether or not to keep occupying a building illegally.”

She quoted British Foreign Office minister Hugo Swire as saying that the referendum result didn’t change the situation “from a legal point of view”…

But President Kirchner also said she wanted to “reiterate our commitment to dialogue, our compliance with United Nations resolutions…. That is the only way to really achieve a solution that also takes into account the interests of the people that live there,” she added.

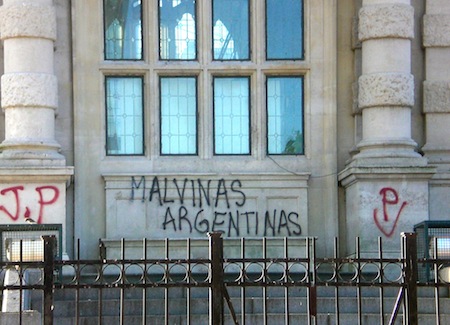

Photo credit to Kevin Lees — Torre de los Ingleses, Buenos Aires, December 2007.

It’s really very complex in this busy life to listen news on TV, thus I simply use internet for that purpose, and

get the hottest news.