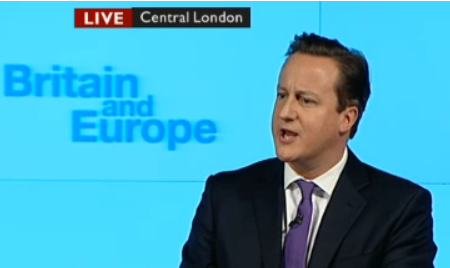

UK prime minister David Cameron, calling the democratic legitimacy of the European Union ‘wafer thin,’ has this morning pledged to renegotiate a new settlement with the European Union for the United Kingdom, and then a straight in-or-out referendum within the United Kingdom by 2017.![]()

![]()

Well, then. Today’s address was probably the most important speech of Cameron’s career and perhaps the most important turning point on UK-EU relations since Britain’s hard-fought entry 40 years ago into what was then the European Economic Community.

Less than a month after the EU fiscal compact treaty goes into effect, and on the day that France and Germany are celebrating 50 years of friendship –as cemented by the Élysée Treaty — no less, Cameron is pledging the referendum that neither his Conservative predecessors as prime minister, Margaret Thatcher nor John Major dared to hold.

Given that the United Kingdom is not (and will not anytime soon) be a member of the eurozone, there’s a rationale for the UK to negotiate a role where it is not subject to the ever-closer political union that the eurozone crisis has required, and it should be clear that the UK won’t cede fiscal and banking policymaking to Brussels when it hasn’t ceded monetary policymaking. But it doesn’t follow that the UK needs to renegotiate those issues; after all, given the ‘Europe at multiple speeds’ approach that’s now reality, the UK has opted out of many EU initiatives — not only the single currency, but also the Schengen Agreement that eliminates internal border controls within the EU.

I’ll have plenty of longer thoughts on Cameron’s gambit later this week.

But for now, as I listen to his speech in real time, here are some initial reactions.

Cameron has ended his speech with a note of caution that the United Kingdom is not Norway and it is not Switzerland, and he’s discussing the benefits of membership in the EU — ‘more powerful in Washington, Beijing, Delhi’ by remaining in the EU — not to mention the free trade benefits of the single market.

By 2017, if there’s actually a referendum, and Cameron’s Tories have won the 2015 general election, I predict that Cameron will be arguing for a ‘yes’ vote on such a referendum.

It’s worth noting that no member-state has ever left the European Union (although Greenland, part of the Danish realm, voted to pull out of the EU in 1985 in order to protect its fishing rights — an issue that’s snagged Icelandic and Norwegian membership in the EU as well).

In the meanwhile, this seems like a political masterstroke — Cameron has pulled a play directly from the political playbook of Labour prime minister Harold Wilson, who held his own referendum on the United Kingdom’s EU membership in 1975 (it won 67,2%).

Consider:

- In giving the euroskeptics a clear referendum on Europe, Cameron has now given them a reason to work hard for a Tory victory in 2015.

- Given the relatively anti-Tory and pro-Europe view of the Scottish, the referendum, scheduled for 2017, need not spook the Scottish toward independence, given the scheduled 2014 referendum within Scotland on Scottish independence.

- He will have quieted the euroskeptic right within his own caucus, notably his former defense minister Liam Fox and other anti-Europe Tories.

- He will have managed to draw some daylight between his party and his coalition partner, the Liberal Democrats, who are incredibly pro-Europe, thereby giving the Lib Dems something with which to distance themselves from the Tories. That will only help win votes away from Labour in 2015.

- He will have taken the steam out of the rising United Kingdom Independence Party, not only for 2015, but for next year’s elections to the European Parliament.

- By keeping the terms of renegotiation vague, Cameron can take any concessions from Europeans and declare victory (say, an opt-out from the working time directive), and push for a ‘yes’ vote in 2017.