Over the weekend, France found itself engaged in a new, if limited, war — and a new theater of Western intervention against radical Islam.

Over the weekend, France found itself engaged in a new, if limited, war — and a new theater of Western intervention against radical Islam.![]()

![]()

French president François Hollande confirmed that French troops had assisted Mali’s army in liberating the city of Konna — in recent weeks, Islamist-backed rebels that control the northern two-thirds of the country had pushed forward toward the southern part of the country, threatening even Mali’s capital, Bamako.

On Tuesday, Hollande said the number of French troops would increase to 2,500, as he listed three key goals for the growing French forces:

“Our objectives are as follows,” Hollande said. “One, to stop terrorists seeking to control the country, including the capital Bamako. Two, we want to ensure that Bamako is secure, noting that several thousand French nationals live there. Three, enable Mali to retake its territory, a mission that has been entrusted to an African force that France will support.”

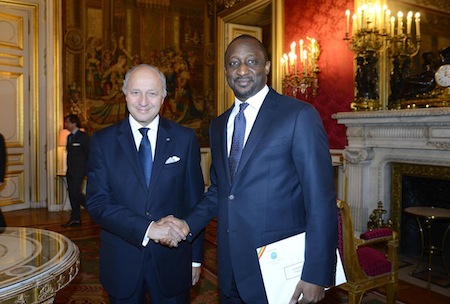

Hollande and his foreign minister, Laurent Fabius (pictured above with Malian foreign minister Tyeman Coulibaly), now face the first major foreign policy intervention of their administration, extending a trend that began under former president Nicolas Sarkozy, who spearheaded NATO intervention in support of rebels in Libya against longtime ruler Muammar Gaddafi and for the apprehension of strongman Laurent Gbagbo in Côte d’Ivoire in 2011.

Foreign Policy‘s Joshua Keating has already called the Malian operation the return of Françafrique. Françafrique refers to the post-colonial strategy pioneered largely by French African adviser Jacques Foccart in the 1960s whereby France’s Fifth Republic would look to building ties with its former African colonies to secure preferential deals with French companies and access to natural resources in sub-Saharan Africa, to secure continued French dominance in trade and banking in former colonies, to secure support in the United Nations for French priorities, to suppress the spread of communism throughout formerly French Africa and, all too often, source illegal funds for French national politics. In exchange, French leaders would support often brutal and corrupt dictatorships that emerged in post-independence Africa.

But to slap the Françafrique label so blithely on the latest Malian action is, I believe, inaccurate — French policy on Africa has changed since the days of Charles de Gaulle and, really, even since the presidency of Jacques Chirac in the late 1990s.

After all, the British intervened just over a decade ago in Sierra Leone to end the decade-long civil war and restore peace for the purpose of stabilizing the entire West African region, and no one thought that then-prime minister Tony Blair was incredibly motivated by contracts for UK multinationals. Given the nature of the Malian effort, it’s quite logical that France — and Europe and the United States — has a keen security interest in ensuring that Bamako doesn’t fall and that Mali doesn’t become the world’s newest radical Islamic terrorist state in the heart of what used to be French West Africa.

Fabius, a longtime player in French politics, and currently a member of the leftist wing of the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party), served as prime minister from 1984 to 1986 and as finance minister from 2000 to 2002, though his opposition — in contrast to most top PS leaders — to the European Union constitution in 2005 has left him with few friends in Europe.

Nonetheless, Fabius argued yesterday that it was not France’s intention for the action to remain unilateral — African forces from Nigeria and elsewhere are expected to join French and Malian troops shortly, UK foreign minister William Hague has backed France’s move, as has the administration of U.S. president Barack Obama — and today, the United Nations Security Council has also indicated its support for France’s efforts as well.

For now, Hollande has the support of over 75% of the French public as well as much of the political spectrum — and it’s hard not to see that the effort will help Hollande, who’s tumbled to lopsided disapproval ratings since his election in June 2012 amid France’s continued economic malaise, appear as a decisive leader. That doesn’t mean, however, that there won’t be trouble ahead for Hollande and Fabius. Over the weekend, former Chirac prime minister Dominique de Villepin excoriated the Hollande administration’s decision in Mali:

L’unanimisme des va-t-en-guerre, la précipitation apparente, le déjà-vu des arguments de la “guerre contre le terrorisme” m’inquiètent. Ce n’est pas la France. Tirons les leçons de la décennie des guerres perdues, en Afghanistan, en Irak, en Libye. [The unanimity of going to war, the apparent haste, the déjà vu arguments of the ‘war against terrorism’ concerns me. This is not France. Let us learn from the decade of lost wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya.]

The challenges are legion:

- Mali’s government remains shaky. The Malian government and its army are incredibly weak under the presidency of caretaker leader Dioncounda Traoré, who previously served as the speaker of the Malian national assembly. The Malian army effected a coup last March over fears about Tuareg rebel activity in the north, ironically providing the conditions to allow Tuareg and Islamist rebels to capture much of northern Mali by the end of the spring of 2012. Although coup leaders ultimately stepped down in favor of Traoré in April 2012, Traoré spent two months out of the country receiving medical treatment following a mob attack on the presidential palace in May 2012. The coup ousted Amadou Toumani Touré, president since 2000, who’s now in exile in Senegal. Touré had been preparing to step down in advance of a presidential election planned for April 2012, an election that Traoré had been contesting. So from the outset, Mali’s current government remains an interim government with no true popular mandate, the result of a coup that represents Malian backsliding on what had been two decades of steadily improving democratic norms.

- Multiple rebel groups have proliferated in the north. The northern rebels are not a monolithic group, but a mix of different groups, each of which have various motives, background and goals. The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) is a longtime secular independence movement among the nomadic Tuareg people who inhabit the Sahel and that dates back to Malian independence in 1960. Initially, last spring, it was MNLA that declared the independent state of Azawad in northern Mali. Ansar Dine, another Tuareg group, is much more Islamist, seeking to impose sharia throughout all of Mali. Since the original crisis began in 2012, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al-Qaeda’s north African wing, has also become a strengthening force comprised of Algerian fighters and other foreign nationals, rather than local Tuareg rebels. AQIM, like Ansar Dine, also seeks to extend Islamic law in Mali, but also to provide a safe haven in sub-Saharan Africa for its global terrorist efforts. Although the MNLA has cooperated in the past with Ansar Dine and AQIM, it’s now less than enthusiastic about the Islamists. An AQIM splinter group — the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA) — is now working to spread jihad throughout west Africa. Each of the groups control different parts of northern Mali at this point — AQIM holds Timbuktu, the iconic city in northern Mali; MUJWA controls Gao and many cities near the borders with Burkina Faso and Niger; and Ansar Dine controls many cities along the border with Algeria. The MNLA controls much of the desert areas near the Mauritanian border. While that fragmentation may help France’s military efforts, it will make any regional and political solution much more complex.

- African-led forces remain a dicey solution. Under UN resolution 2085, the African-based intervention force was supposed to be launched in September to stabilize Mali, but French officials obviously believed that was about eight months too late to save Mali from falling to Islamist forces. Even though Hollande’s express goal is to provide the time and space for Malian and pan-African to complete the effort to secure Mali, it remains uncertain whether any such force will have the muscle to carry through that mission. Mauritania, which lies to Mali’s west, is unlikely to provide much direct support out of fear that MUJWA and AQIM will try to overthrow the Mauritanian government as well, further destabilizing west Africa. And although Algeria is allowing France to use its airspace, it’s certainly not too interested in joining forces alongside the colonial power with which it fought a bloody war of independence in the 1960s.

- Mission creep and unintended consequences. It’s of course difficult to know when exactly France will consider Bamako to be ‘secure’ and when Mali’s forces will be in a position, if ever, to launch an effort to retake the south. To some degree, the current rebel forces in Mali are a direct result of NATO intervention in Libya — when rebels finally defeated Gaddafi, many of the Western-supplied arms provided to those rebels found their way into the hands of the Tuareg and Islamist rebels in northern Mali. Furthermore, many of the MNLA and Ansar Dine gained crucial experience fighting alongside Gaddafi in 2011. Likewise, there’s no way of knowing what French intervention in Mali, in turn, could spawn — by internationalizing the conflict, France may be endangering not only west Africa, but risk the gains that Tunisia and Libya have made in North Africa as well.

5 thoughts on “M. Hollande’s little war — and what it means for French-African politics”