This weekend’s Czech presidential election resulted in something of a surprise, with center-right foreign minister Karel Schwarzenberg (pictured above) surging to a very close second place against front-running center-left candidate and former prime minister Miloš Zeman.![]()

Zeman and Schwarzenberg will now compete in a runoff to be held on January 25 and 26 in the Czech Republic’s first direct presidential election in its post-Cold War history to succeed Václav Klaus, the Czech Republic’s president since 2003, an outspoken conservative and euroskeptic.

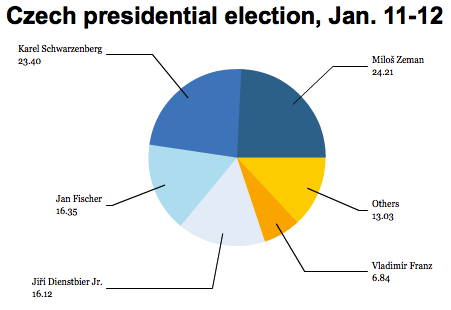

Schwarzenberg won a surprisingly high 23.40% of the vote, trailing less than 1% behind Zeman, edging out a statistician and former caretaker prime minister Jan Fischer, who won just 16.35% and nearly finished in fourth place behind another center-left candidate, Jiří Dienstbier Jr. Fischer led polls as recently as a week or two ago, though his performance in a debate against Zeman in early January was seen as lackluster, fueling a boom for Zeman’s poll support heading into last weekend’s vote.

Ominously for the current Czech government, the candidate of the governing Občanská demokratická strana (ODS, Civic Democratic Party), Přemysl Sobotka, a senator, finished in 8th place with just 2.46% of the vote, likely a result of his relatively obscurity in a field of longtime titans of Czech political life and of the brutal austerity measures that the current ODS-led government of Petr Nečas.

Schwarzenberg won throughout the center of the country in his native Bohemia and in Prague and other urban areas; Zeman dominated much of the rest of the country, including rural Moravia in the east and rural areas in the north.

So what should we expect in the final runoff?

Obviously, polls were not incredibly accurate — Schwarzenberg more than doubled the level of support that he had been winning in polls, and Dienstbier, the candidate of the Česká strana sociálně demokratická (ČSSD, Czech Social Democratic Party), also did much better than polls suggested.

The most natural expectation is that many of Fischer’s voters are likely to back Schwarzenberg, a Bohemian prince who leads liberal conservative Tradice Odpovědnost Prosperita 09 or ‘TOP 09′ (Tradition Responsibility Prosperity 09), which is currently the second-largest party in Nečas’s governing coalition. The surest explanation of what happened over the weekend is that voters who originally backed Fischer turned to Schwarzenberg instead and, indeed, they both inhabit largely the same centrist, conservative space.

It also seems likely that many of Dienstbier’s voters will ultimately back Zeman, a one-time leader of the ČSSD and a prime minister from 1998 to 2002. But he left the ČSSD after falling out with its leadership in 2009 to form a new party, the Strana Práv Občanů – Zemanovci (SPOZ, Party of Civil Rights — Zemanovci). Furthermore, Klaus endorsed Zeman in the election, despite their ideological differences, which may make a Zeman vote more difficult for Dienstbier supporters.

In many ways, Zeman, a brash populist, is the natural heir to Klaus; like Klaus, Zeman would not be shy to voice an often-controversial opinion as president. Although Schwarzenberg is to the right of Zeman, he’s as much pro-Europe as Klaus is anti-Europe, and Dienstbier supporters might ultimately view the relatively genteel Schwarzenberg a better choice for president than the sharp-elbowed Zeman. Dienstbier supporters might also fear that a Zeman presidency could split the Czech center-left, generally, and the ČSSD, specifically.

Schwarzenberg, aged 75 and known for nodding off in government meetings, is ironically portraying Zeman as ‘yesterday’s man.’ A prince from Bohemia, who spent the first four decades of his life in Austria, he’s served as foreign minister from 2007 to 2009 and currently since 2010. In the 2010 Czech elections, his TOP 09 party was by far the big winner, coming into the Czech parliament for the first time with 41 seats, with the ČSSD losing 18 seats and the ODS losing 28.

In many ways, Schwarzenberg is perhaps better placed to defeat Zeman in the upcoming runoff than Fischer was.

Unlike Fischer, whose personality is mild-mannered, Schwarzenberg is just as outspoken (if perhaps more polite) as Zeman, and he’ll certainly bring a colorful contrast to Zeman.

Also in contrast to Fischer, who was dogged by his past membership in the Czech communist party (albeit only to retain his job as a government official), Schwarzenberg worked from Austria throughout the Cold War, and especially in the 1980s, to support dissidents in then-Czechoslovakia.

He was very close to dissident intellectual and playwright Václav Havel, who became the first president of the Czechoslovakia in 1989 and thereupon, after the split between Slovakia and the Czech Republic, the Czech president until 2003, and Schwarzenberg’s historical and personal ties to Havel, who died in 2011, will undoubtedly help him in the runoff.

4 thoughts on “Zeman and Schwarzenberg to face off for Czech presidency”