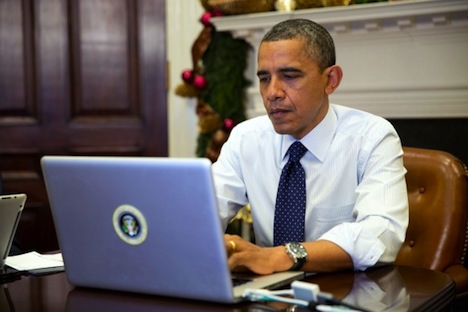

Just a week after US president Barack Obama in essence fired his defense secretary, former Republican senator Chuck Hagel of Nebraska, he has apparently found a successor — Ashton Carter.![]()

Carter served as deputy secretary of defense between October 2011 and December 2013 under both Hagel and Hagel’s predecessor, Leon Panetta, a longtime Democratic operative, former budget chief, Clinton administration chief of staff and California congressman.

Carter, who graduated from Yale University with majors in medieval history and physics, has an extensive background as under secretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics. He is a Rhodes scholar with a doctoral degree in physics as well.

As a defense secretary, he will be more like Panetta or Robert Gates, a master of the Pentagon and its bureaucracy and budget. He isn’t expected to be a visionary, like former Bush-era defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, which is just as well, given that so much national defense policymaking is centered in the White House, not at the Pentagon. Nevertheless, The Atlantic‘s editor-at-large, Steve Clemons noted earlier on Tuesday on Twitter that Carter is hawkish with respect to Iran, which could nudge administration policy, a week after stalled negotiations over Iran’s nuclear weapons program were extended until July 2015.

* * * * *

RELATED: Hagel’s exit symbolizes Obama policy shift

* * * * *

Unlike Hagel (or even Panetta), Carter is not a politician, but rather a career technocrat and policy wonk. As an assistant secretary of defense under US president Bill Clinton, Carter was responsible for international security policy, and he has written extensively on the topic of nuclear non-proliferation.

When Obama was looking to replace Panetta two years ago, Carter was on the short list as well, and there were indications that Hagel and Carter didn’t always see eye-to-eye at the Pentagon, one reason why Carter may have stepped down as deputy secretary late last year.

His background from the immediate post-Cold War period makes Carter especially cognizant of many issues in the former Soviet Union, perhaps an especially relevant qualification as Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine (and perhaps the Baltic states and Georgia) increases.

Carter is easily expected to win confirmation by the US Senate, which will be Republican-controlled as of early January, following Republican gains in both houses of the US Congress in November’s midterm congressional elections.