Every Peruvian president comes into office a lame duck.![]()

Such are the drawbacks to a system designed to prevent presidents from seeking reelection. Each president has five years — at least by the standards of recent history (and with the exception of Alberto Fujimori, the authoritarian who ran Peru from 1990 to 2000).

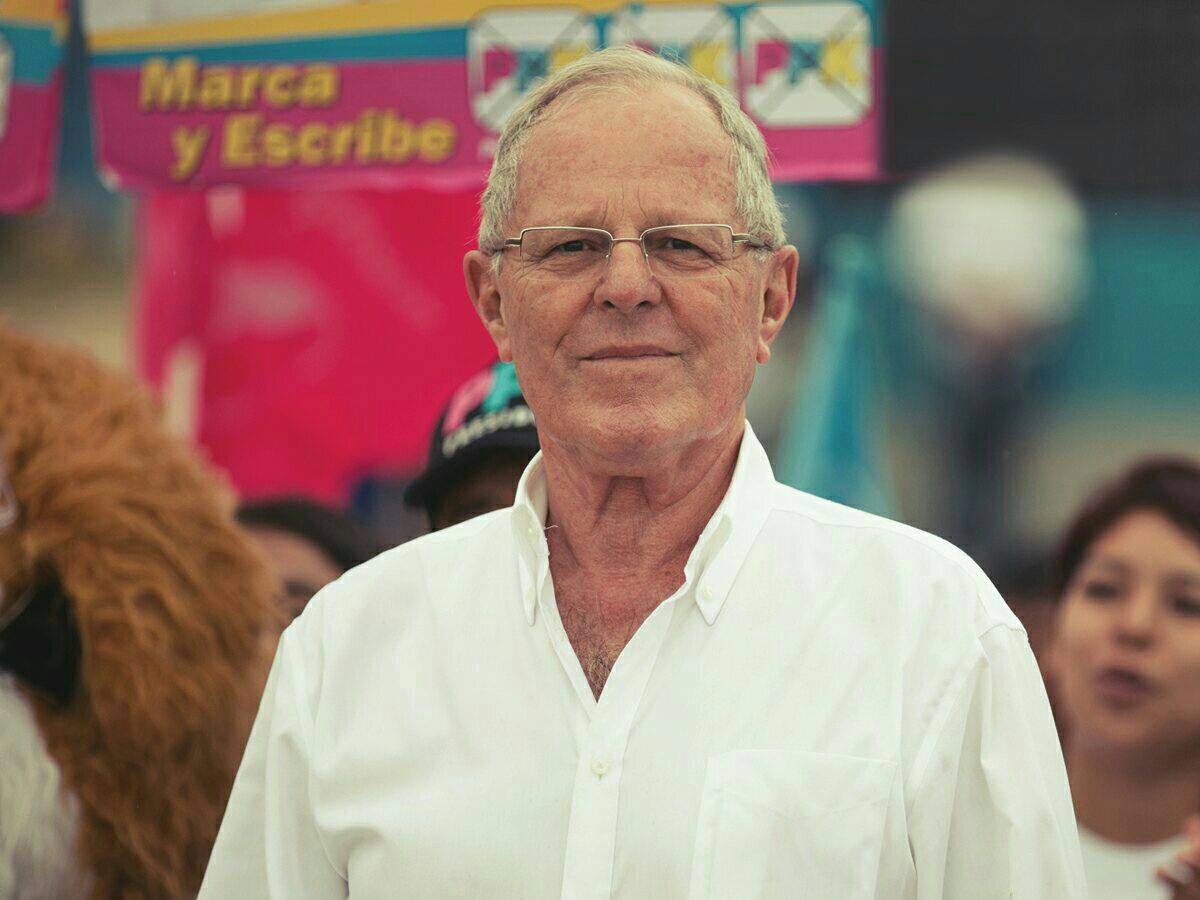

That was always likely to be the fate of the 78-year-old Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, who came into office at the end of a long career in both domestic politics and international economics and whose chief political skill was not being related to Fujimori.

But PKK (he’s known universally by his initials) only unexpectedly won the presidency last June. Investors cheered his narrow victory over Keiko Fujimori, the former president’s daughter, who waged an economically populist and right-wing campaign in her second attempt at the presidency.

But to what end?

With no working majority in Peru’s Congress, Kuczynski now faces a tough choice: cave in to political opponents to pardon the Fujimori (also 78 years old) on ‘humanitarian grounds’ or face four more years of gridlock. Plans for reforms to tackle institutional corruption and spur the flagging economy would come to naught.

Keiko Fujimori dominated the first round of last year’s presidential election. PPK, a former World Bank economist and Wall Street banker, narrowly made it into the presidential runoff last year, winning nearly one-half the votes that she did. He only narrowly eclipsed rising star Verónika Mendoza, a left-wing figure who won widespread support in the Peruvian south. An even more popular former official, Julio Guzmán, was disqualified under sketchy circumstances. PPK won the runoff by the narrowest of margins as the anti-Fujimori forces coalesced around his candidacy.

But with nearly 40% of the first-round vote, Fujimori’s showing was easily strong enough to win control of the unicameral, 130-seat Peruvian Congress, which was elected simultaneously in last year’s first round. Her party, Fuerza Popular (FP, Popular Force), holds 72 seats, an outright majority. By contrast, the fledgling movement formed in favor of PPK, the cheekily named Peruanos Por el Kambio (Peruvians for Change) holds only 17 seats, behind Mendoza’s socialist Frente Amplio (Broad Front), which holds 20.

It’s an unprecedentedly weak position for a sitting president. After the 2011 election, leftist president Ollanta Humala controlled 47 seats, the largest congressional bloc (if still a minority). Even in 2006, president Alan García’s APRA managed to win 36 seat, the second-largest bloc after Humala’s forces. Continue reading Opponents force PPK to consider pardoning former dictator Alberto Fujimori