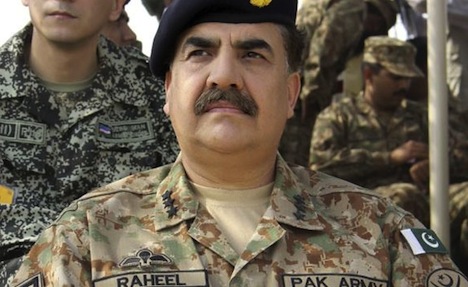

Ending months of speculation, Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif announced late last week that Raheel Sharif (pictured above) is his choice to succeed Ashfaq Kayani as Pakistan’s new army chief of staff last week, just hours before Kayani’s resignation went into effect.

Though the two men share the same surname, it’s an open question as to which Sharif will be the more powerful person in Pakistani government over the years to come. The army chief of staff will significantly influence issues of security and foreign policy, including long-term prospects for more peaceful Indian-Pakistani ties, patrolling Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan (all the more relevant given that the US military pullout is likely to occur in 2014), dealing with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (commonly referred to as the Pakistani Taliban), and the bilateral relationship with the United States, including the difficult issues of sovereignty and civilian deaths resulting from US drone strikes in northwestern Pakistan.

While Raheel Sharif may not exactly be able to set Pakistan’s policy on these issues, he can certainly complicate the civilian government’s policy decisions on security and foreign policy if he believes that they aren’t in the Pakistani military’s best interests.

What’s most interesting about the decision is that the last time Nawaz Sharif selected a new army chief of staff, as Pakistan’s prime minister in 1998, his choice was Pervez Musharraf, the third-most-senior officer at the time, who Sharif hoped would chart a more harmonious course in line with Sharif’s security policy than Jehangir Karamat, who Sharif dismissed earlier in 1998. Within a year, however, Musharraf had ousted Sharif in a military coup, ushering in yet another era of military government in Pakistan that would last nearly a decade, and which coincided with intense cooperation between the United States and Pakistan with respect to Afghanistan and, more generally, US military efforts against radical Islamic terror across the Middle East, South Asia and Africa.

Given the ominous precedent, it was important for Sharif to choose very wisely this time around — and so far, there’s every indication that the new army chief of staff, though somewhat of a surprise pick, is unlikely to pursue a radically different path from Kayani, who has worked hard to keep the Pakistani military’s policymaking role behind the scenes since his appointment in 2007. Kayani is credited, in part, with providing the backdrop of security and stability that allowed for the first government in Pakistani history to serve out its full five-year term, and his commitment to stable, civilian-led government is perhaps his chief legacy.

In choosing Raheel Sharif, Nawaz Sharif decided against Haroon Aslam, the most senior military officer, who was viewed as the frontrunner, and against Rashad Mehmood, who served as Kayani’s principal staff officer and has also served in the Inter-Services Intelligence, the top Pakistani spy agency.

Raheel Sharif was born in 1956 in Quetta, which is located in the relatively remote province of Balochistan in Pakistan’s southwest, and he comes from a family with a long military tradition — his brother was killed in the 1971 war with India and was awarded Pakistan’s highest military honor, the Nishan-i-Haider. Though just third in line in terms of military seniority, he has developed new training doctrines under Kayani’s leadership in transitioning the Pakistani army away from its traditional focus on India and toward a role based in counterinsurgency strategy. He has ties to both top army officials and the political elite and, in particular, is close to lieutenant-general and tribal affairs minister Abdul Qadir Baloch, who’s a key confidante to the prime minister.

Five years after returning to Pakistan and five years after the transition back to civilian rule, Nawaz Sharif returned to power after May’s parliamentary elections, which saw Sharif’s Punjab-based, center-right Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML-N, اکستان مسلم لیگ ن) win a landslide victory against both the Sindh-based, center-left Pakistan People’s Party (PPP, پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی) of Asif Ali Zardari, Pakistan’s former president and widower of assassinated prime minster Benazir Bhutto, and the anti-corruption, populist Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Movement for Justice or PTI, پاکستان تحريک) of Imran Khan.

Upon becoming Pakistan’s prime minister for a third time, Sharif championed a politically negotiated settlement with the TTP and also better economic and security ties with India. In both cases, the Pakistani military has undermined his goals behind closed doors. Continue reading Who is Raheel Sharif? A look at Pakistan’s new army chief of staff