As unbelievable as it seems, the Jean Charest era is firmly over in Québécois politics.![]()

![]()

Philippe Couillard, his former minister of health and social services, is now the leader of Québec’s Parti libéral du Québec (Liberal Party, or PLQ), which narrowly lost its reelection campaign in September 2012 for what would have been a fourth consecutive term in government under Charest.

As expected, Couillard won on the first ballot with 58.5% of the vote — the convention lacked the drama of January’s Ontario Liberal Party convention that saw Kathleen Wynne win the leadership in Canada’s largest province, thereby paving the way for Wynne to succeed Dalton McGuinty as Ontario’s premier.

So who is Couillard and what does his elevation as Québec’s chief opposition leader mean for the province and for Canada?

A neurosurgeon by training, Couillard came to provincial government in 2003 as a member of the provincial legislature from Mont-Royal, a constituency in Montréal, though he stepped down in 2008 after a relatively successful stint as health minister, where he oversaw a ban on public smoking in the province.

During the leadership race, Couillard received criticism for his partnership with Arthur Porter, the former head of McGill University’s health center, who is living in the Bahamas and wanted on fraud charges in respect of a 2010 contract to build McGill’s new hospital — Couillard had partnered with Porter for a consulting venture in 2008 upon returning to the private sector.

Couillard must now win a seat in the Assemblée nationale du Québec, although he may well wait until the next election, and he’s said that winning a new seat is not a top priority for him — Jean-Marc Fournier, who served as the interim party leader, will continue for now as the PLQ floor leader in the provincial assembly. Because the current sovereigntist Parti québécois (PQ) holds only a minority government under premier Pauline Marois, Québec could return to the polls, perhaps even within the year. So it’s fair that rebuilding and rebranding Québec’s Liberal Party is a more pressing task for Couillard in the months ahead.

Unlike Charest, who worked to keep a lid on the fraught constitutional politics that afflicted Québec in the 1970s and the 1990s, Couillard has wasted no time in calling on the province to become a signatory to Canada’s 1982 constitution by the year 2017 — a move that’s already generating controversy both inside Québec and outside:

“We need to be methodical in the way we are going to approach this,” said [Couillard]… “The first thing to do is within our party, to discuss this question of identity or the specific nature of Quebec and then have conversations with the other governments of Canada on how this could be approached.”

He proposed that a new round of constitutional talks could include other issues, such as prime minister Stephen Harper’s proposal to reform the Senate. “This could be one window of opportunity,” he said adding that another more “symbolic window” would be the 150th anniversary of Confederation.

That’s slightly perilous talk for any Canadian politician in light of the constitutional battles of the early 1990s — the 1990 Meech Lake accord failed and Canadians voted down the Charlottetown accord in a 1992 referendum, one of the reasons for the implosion of Progressive Conservative prime minister Brian Mulroney’s government. Three years later, Québec voted by only the narrowest of margins to remain within Canada in a referendum on its future status.

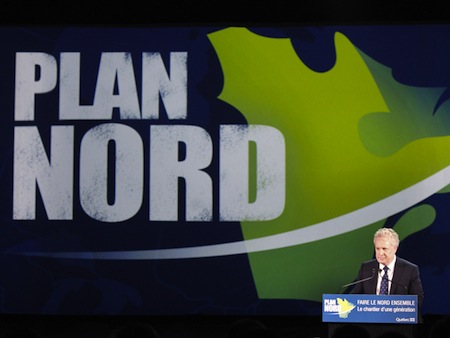

Charest, a federalist who led the Progressive Conservatives in the 1997 Canadian federal elections, left national politics for provincial politics in 1998, and his Québec premiership sought to downplay constitutional and sovereignty issues.

Couillard has also criticized Marois’s government for its proposed Bill 14, which would make Québec’s French language laws even stricter by revoking the ‘bilingual’ status of municipalities with less than 50% anglophone population, introduce a mandatory French proficiency test for Québécois students, and prevent small businesses (less than 25 employees) from using English in the workplace. Continue reading Who is Philippe Couillard?