The most interesting contest in Sunday’s first round of the French parliamentary election may well be the most irrelevant to determining whether President François Hollande’s center-left or the center-right will control the Assemblée nationale — but it also showcases that the far-left and far-right are both playing the strongest role in over a decade in any French legislative election.

The race is the 11th precinct of the Hénin-Beaumont region, where Front national leader Marine Le Pen is running against Front de gauche leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Le Pen originally targeted the region in 2007 (where she won 24.5% of the vote) — it’s an economically stagnant area where coal mining was once the major economic activity. Think of it as the part of Wallonia that’s actually part of France.*

Like many of the old French Parti communiste strongholds, it is today receptive to the economic populist message of the Front national — in the first round of the presidential election, Le Pen won 35% there, followed by Hollande with 27% and Nicolas Sarkozy with just 16%.

So it’s a constituency that Le Pen continues to view as fertile ground, a great pickup opportunity in what seems to be the Front national‘s best shot at seats in the Assemblée nationale since 1997.

Mélenchon, however, decided to parachute into the precinct to run against Le Pen (although neither have true roots in the region), prolonging the bitter antagonism that marked the presidential race. In the spring, their enmity seemed greater than even that between Hollande and Sarkozy.

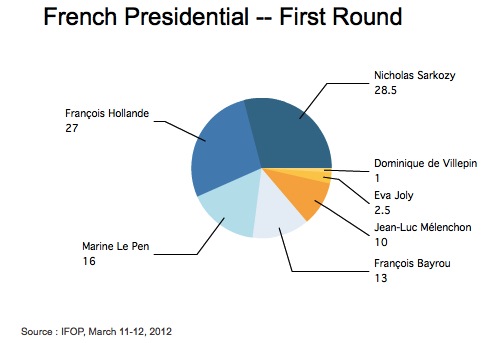

Mélenchon’s eagerness to attack the Front national led to a surge of support in the first round. Although Mélenchon won less than some polls indicated he could have, his 11% total was still the best presidential result for the far left in two decades.

For a time, it looked as if Mélenchon’s move was a masterstroke — he would secure a seat for the Front de gauche and in so doing, polls showed, would become the left’s champion in defeating Le Pen. As predicted, the campaign for Hénin-Beaumont has become a battle royale between the far left and the hard right, with rhetoric matching that of the presidential campaign:

“I find it funny the passion he has developed for me and that he follows me all across France,” Ms Le Pen remarked to a group of journalists at her constituency headquarters in the recession-hit town of Hénin-Beaumont. “But it is good. He divides people. There are people who would not vote for me if he wasn’t here.”

Speaking earlier as he greeted shoppers in a street market in neighbouring Noyelles-Godault, Mr Mélenchon brushed aside the innuendo that he has some kind of obsession with his rival.

“I do not find her erotic, as I have read in certain newspapers,” he protested. He had become a candidate in Hénin-Beaumont to “shine a light on the vampires” of the National Front, he said. It would be “absolutely shaming” for the left if Ms Le Pen were elected in a former mining area “at the heart of the history of the French workers’ movement”.

And so on.

But as the campaign concludes, polls show an uptick for Parti socialiste candidate Philippe Kemel, who had previously polled far behind the two national stars — even the retiring PS deputy had abstained from endorsing Kemel.

Two polls on Wednesday showed a tight race, however: Continue reading Le Pen and Mélenchon battle in Hénin-Beaumont precinct highlights four-way French campaign →

![]()