The sound that you heard Sunday evening?![]()

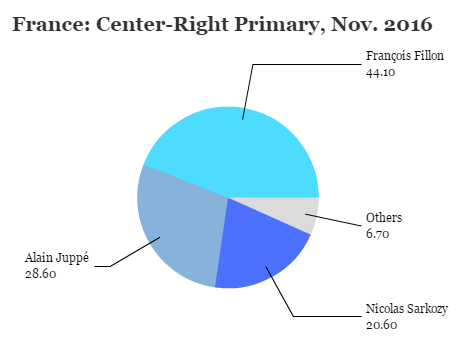

A sign of relief across the liberal democratic world that former French president Nicolas Sarkozy sank to third place in the presidential primary of the center-right Les Républicains (the Republicans), the successor to the party that Sarkozy once led and that he helped to rechristen and remake over the last two years.

Instead, his former prime minister, François Fillon, a social conservative who promises Thatcher-style reforms to the French economy, and his former foreign minister (and long-ago Chirac prime minister) Alain Juppé, who has promised a far more moderate approach to governance than either Sarkozy or Fillon, will head to a runoff next Sunday, November 27.

But with Fillon’s dramatic first-place finish, following a week-long reversal in the polls for both Sarkozy and one-time frontrunner Juppé, and with Sarkozy’s quick endorsement of Fillon’s candidacy, Juppé appears to have a limited path to victory next week.

Fillon may or may not prove a stronger candidate than Juppé. But he most certainly will be stronger than Sarkozy.

No matter what you thought of his presidency, Sarkozy’s defeat is good news for everyone on the right, middle and left who hopes to prevent Marine Le Pen, the leader of the anti-immigrant and eurosceptic Front national (National Front) from winning the presidency in May 2017. France chooses a president in two rounds — the two individuals with the most votes in a first-round April vote advance to a May runoff. Polls show today that Le Pen would almost certainly win one of those two runoff spots.

Sarkozy, more than Juppé or Fillon, was willing to run in 2017 (much as he did in 2007) by co-opting the language, if not the outright policies, of the far right. On immigration and crime, in particular, Sarkozy telescoped that he would compete with Le Pen primarily on her own turf. For many French voters who find Le Pen’s views on immigration, Islam, and the European Union repugnant, Sarkozy would have reinforced and normalized those views, pulling Le Pen closer to the heart of France’s political debate.

In 2007, Sarkozy effectively sidelined Le Pen by co-opting her rhetoric. That, in retrospect, only empowered Le Pen and her movement. In 2017, Le Pen will prove a far greater threat. French voters have now rejected Sarkozy (in 2012), and his leftist rival François Hollande, featuring approval ratings as low as 4%, faces a quixotic hope for reelection. With the French electorate so unhappy with the status quo, and after the shocking victories for Brexit in the United Kingdom and for Donald Trump in the United States, Le Pen must now be taken seriously as a threat to win the Élysée Palace next spring.

Even as Sarkozy’s nomination would have emboldened Le Pen and the illiberal, populist right, he would have simultaneously embodied everything that many French voters despise — the ostentatious ‘bling-bling’ nature of his presidency, the drama of his whirlwind romance with Carla Bruni, the attempts at neoliberal reform that voters have come to blame for inequality and stagnation. Even worse, Sarkozy would have gone into the 2017 elections under a legal and ethical cloud that aggregates several lawsuits and scandals, not least of which the notion that he received political funding from Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi in his 2007 election.

With the French left in tatters after Hollande’s disastrous and ineffective presidency, and with several figures on the left likely to compete for votes in the first round, Sarkozy might well have ended up as Le Pen’s challenger in the runoff, where he would have been an easy foil for Le Pen as the compromised avatar of a failed French political establishment — just as Trump so effectively demolished the scions of the American political establishment in Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton.

It’s true that Juppé and Fillon both carry baggage as figures associated with the French political establishment. So, too, will Emmanuel Macron, a former Hollande economy minister who announced earlier this month that he will stand as an independent in the presidential election (and who might eventually outpace Fillon to the runoff). So, too, will Hollande or the eventual nominee of Hollande’s leftist Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party).

But Sarkozy would have personified the worst of the French political establishment while also giving political cover to the National Front’s far-right views on politics and policy. Fillon, Juppé, Macron and the eventual Socialist nominee (likelier than not the brash, Spanish-born centrist prime minister Manuel Valls) will all certainly talk tougher about immigration and security in 2017, given the traumatic Charlie Hebdo, Bataclan and Nice terrorist attacks. None of them, however, seem poised to parrot the Le Pen line on immigration or on France’s Muslims to the extent Sarkozy was willing.

The Le Pen threat, now much more tangible than it was before Trump’s election two weeks ago, is still a serious one. But classic economic liberals and social liberals, on both the right and the left, should be relieved that they will not have to rally around such a clearly flawed candidate as Sarkozy at a time when Le Pen’s support is cresting.