As conference season gets underway in the United Kingdom, the Labour Party, under relatively new leader Ed Miliband, now leads the Conservative Party by a 41% to 31% advantage in the latest Guardian/ICM poll, with the Liberal Democrats trailing at 14%.![]()

Labour, which performed generally better than expected in the last election in May 2010 (which was supposed to have been a complete landslide for the Tories), hold 254 seats in the House of Commons to 304 seats for the Tories and 57 seats for the Lib Dems. Although the next election is not expected until 2015, and the current Tory-Lib Dem coalition shows no signs of fracturing, despite some strains, Labour would be set to return to government. That’s the best poll performance for Labour since well before the era of former prime minister Gordon Brown.

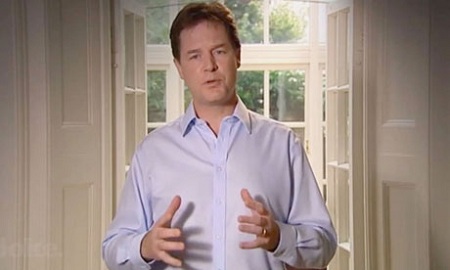

The support comes largely from the drop in support for the Lib Dems, who won 22% in the 2010 election and have watched support crumble as the junior partner of UK prime minister David Cameron’s government. Just last week, Lib Dem leader and deputy prime minister Nick Clegg (pictured above) recorded an apology for violating its 2010 pledge not to raise tuition fees — the Tory/Lib Dem coalition has voted to lift the cap on tuition fees to £9,000.

The move, which came in advance of this week’s annual Lib Dem conference, has dominated political discussion — Clegg’s video has even gone viral:

As we approach the expected 2015 election, if Lib Dem support remains subdued, the calls for a new leader will only become louder. This week’s favorite is Vince Cable, who has been the business secretary in the coalition cabinet since 2010. That’s perhaps ironic, given that Cable is just as pregnant with support for the central Tory program of budget cuts as Clegg. Nonetheless, the Guardian/ICM poll showed that the Cable-led Lib Dems would increase their support to 19% from 14%.

Throughout the conference, Cable and Clegg have both emphasized that the Lib Dems will run in the next election as a separate party, not jointly with the Tories or in favor of any particular coalition.

All things considered, today’s polls are of limited utility nearly 30 months before the next election. Furthermore, I still think — despite a strong performance by shadow chancellor Ed Balls and an increasingly sure footing for Ed Miliband — that the polls are a reflection less of Miliband’s stellar leadership than of the collapse of the Lib Dems under Clegg and the tepid reviews of Cameron’s Tories, given the austerity program that chancellor David Osborne is pushing forward with, even with the UK mired in a double-dip recession. So there’s much time for the economy to turn around, and if so, Cameron and Clegg will both in better shape going into an election expected in 2015, and Miliband still seems like (and remains closer to) Neil Kinnock, the perennial loser of the 1980s and 1990s British politics than to Tony Blair, who delivered three consecutive Labour routs.

The left has savaged Clegg because he refused to apologize for the actual hike in tuition fees (and not just for breaking the pledge), but the more damning criticism is that by offering up such a mealy-mouthed apology and by refusing to stand up to the Tories on not just student fees, but the direction of the economy, Clegg sounds like just another politician. Given that Clegg’s ascent into government came largely from his freshness and the appeal of a new approach to government (Cleggmania!), that is perhaps the most dangerous aspect for Clegg’s leadership. Continue reading Labour leads, as Clegg and the Lib Dems struggle during UK convention season