<See below Suffragio’s preview of Honduras’s November 2013 presidential and parliamentary elections, followed by a real-time listing of all coverage of Honduran politics.>

TEGUCIGALPA — Honduras, with over eight million residents, is the second-most populous country in Central America, and its November 24 general election is arguably the most important of four upcoming Central American elections (alongside El Salvador, Costa Rica and Panamá) between November 2013 and May 2014.

Hondurans will elect a new president and all 128 members of the Congreso Nacional (National Congress). Under the Honduran constitution, the president is limited to a single four-year term, so the incumbent, Porfirio Lobo Sosa, is ineligible for reelection.

The presidential election is a one-round, plurality vote. The two-party system that has featured in Honduran politics in the 20th century and, especially, since the return of regular elections in 1981, has meant that the winner typically achieves over 50% of the vote, though the current three-way race means that no one is likely to win with an absolute majority this time around.

The same dynamic applies with the National Congress because there’s a strong chance that no single party will emerge with an absolute majority. A certain number of deputies are elected from each of the 18 departments of Honduras on an open-list proportional representation basis — for example, the department of Francisco Morazán, which includes Tegucigalpa, the capital, and surrounding areas, will elect 23 deputies.

Since 1981, the conservative Partido Nacional (PN, National Party) has won three elections, including Lobo Sosa’s victory in the most recent November 2009 election. The centrist Partido Liberal (PL, Liberal Party) has won five elections, including Manuel Zelaya’s victory in the November 2005 election. This month’s presidential election is the second since the Honduran armed forces ousted Zelaya from power in June 2009 — Zelaya had pulled the country increasingly to the left, and when he was deposed, he was attempting to revise the constitution to provide for presidential reelection.

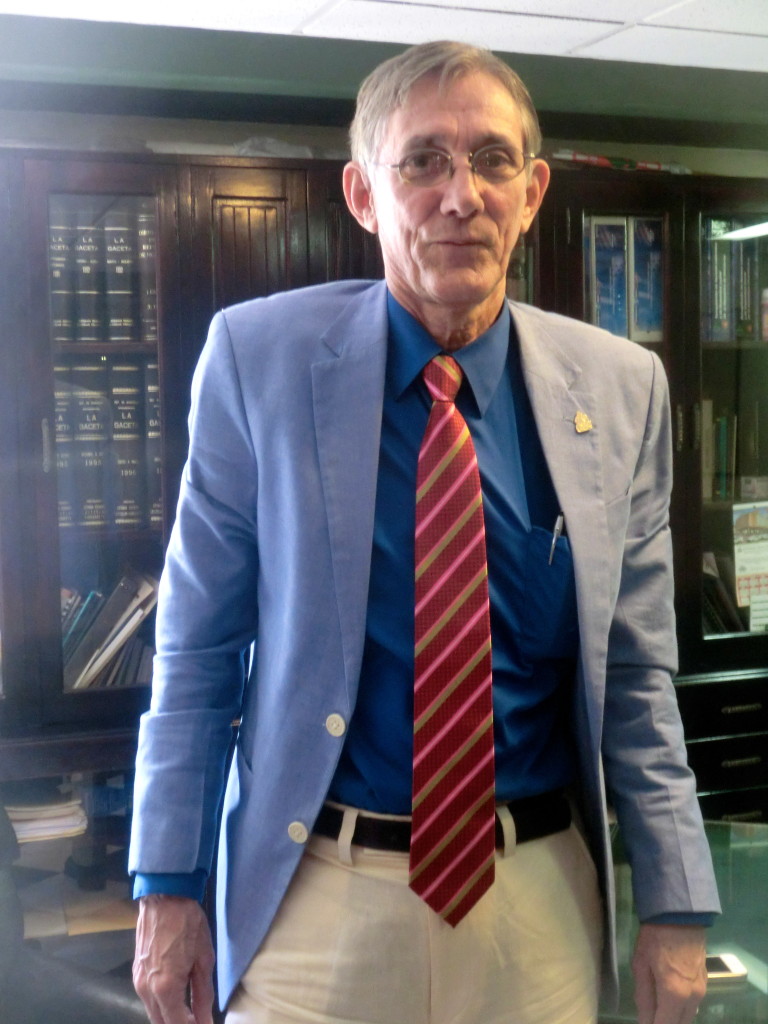

Juan Orlando Hernández (pictured above), who’s currently the president of the National Congress, is the candidate of the National Party. He’s running on a platform of greater security through the development of a military police, designed to be shielded from the corrosive corruption that’s captured much of the Honduran police and the Honduran military as the country has become an increasingly popular transit point for drug traffickers. That, in turn, has given Honduras the distinction of the world’s highest homicide rate (just over 90 per 100,000 annually). Critics worry, however, that the military police will commit human rights abuses, especially in light of the various politically motivated murders in the past four years that have targeted not only leftist opponents of the 2009 coup, but also LGBT activists and journalists.

His major opponent is Xiomara Castro de Zelaya (pictured above), the wife of the former president. Both Zelayas left the Liberal Party to help form the Partido Libertad y Refundación (LIBRE, Party of Liberty and Refoundation), the first truly leftist party in Honduran political history, which emerged out of the grassroots opposition to the 2009 coup. Since that time, LIBRE has attracted much of what used to be the left wing of the Liberal Party as well as a grab-bag of various human rights activists, including top labor, LGBT, women’s rights, indigenous and Afro-Honduran interests. Critics argue that Xiomara’s campaign amounts to a second term for her husband. While Xiomara’s platform is in many ways an extension of the Zelaya agenda from between 2005 and 2009, including a controversial renewed attempt to amend the Honduran constitution, she has also emphasized a community-based approach to policing, and greater spending to boost the economic fortunes of small farmers and businesses.

Mauricio Villeda (pictured above), the candidate of the Liberal Party, by most polling surveys, is stuck in third place. An attorney from the conservative wing of the Liberal Party, Villeda has a reputation as an honest politician, if somewhat uninspiring. His father, Ramón Villeda Morales, served as Honduras’s president from 1957 to 1963, effecting a broadly social democratic agenda that improved public education, social welfare and public health. The residual strength of the Liberal Party, however, and Villeda’s moderation (as between Castro de Zelaya and Hernández) means that undecided voters may turn to Villeda in the final months of the campaign.

A fourth candidate, sports announcer Salvador Nasralla, is running under the newly formed, right-wing Partido Anticorrupción (Anti-Corruption Party) and while polls showed Nasralla in the top tier of presidential candidates earlier this year, Nasralla’s support has largely dropped as more voters appear to back Hernández.

Given that Zelaya tried to move Honduras closer to leftist regimes like Venezuela and Ecuador, thereby distancing it from a longtime alliance with the United States, the result will have significant consequences for US policy in Central America. The United States holds a strategic air force base (Soto Cano) in Honduras and, throughout the past four years, the United States has massively increased military aid for Honduras’s anti-trafficking efforts, despite the country’s less-than-stellar human rights record. Moreover, the June 2009 coup marked one of the first major foreign policy crises for US president Barack Obama (pictured above with Lobo Sosa) — while the United States denounced the coup and the interim government of Roberto Micheletti, US policymakers ultimately recognized the interim regime’s elections that brought Lobo Sosa to power. No one doubts that US policymakers in 2009 weren’t incredibly upset to see the end of the Zelaya regime, and no one doubts that US policymakers would find a Zelaya resurgence in 2013 to be incredibly productive for US-Honduran relations.

Find below all of Suffragio‘s coverage of the Honduran election:

Hernández takes office with agenda already largely in place

January 27, 2014

Huffington Post: Honduran LGBT activists fear ongoing threat upon Hernández inauguration

January 24, 2014

Results of the Honduran parliamentary election — a gridlocked National Congress

December 14, 2013

How the Obama administration is failing Honduras — and Central America

December 6, 2013

A photo-op that Xiomara Castro couldn’t have pulled off

December 4, 2013

Americas Quarterly: Hernández edges toward Honduran presidency with no mandate, no majority and no money

November 26, 2013

LIVE BLOG — Honduras election results coming in: both Juan Orlando, Xiomara declare victory

November 24, 2013

McClatchy: ‘Whatever it takes’ — a look at the militarization of Honduras’s police force

November 22, 2013

An interview with Germán Leitzelar, Honduran congressman and former labor minister

November 22, 2013

An interview with Rasel Tomé, LIBRE party founder and congressional candidate

November 22, 2013

An interview with Dr. Leo Valladares, former Honduran human rights commissioner

November 22, 2013

Will the Honduran general election be conducted fairly?

November 21, 2013

LIBRE, Nasralla could leave no party with majority in Honduran Congress

November 20, 2013

Five reasons why Mauricio Villeda could still win the Honduran presidency

November 19, 2013

The New Republic: Why gun control legislation is a non-starter in Honduras

November 19, 2013

Photo essay: campaign season in Honduras

November 6, 2013

Juan Orlando versus Xiomara: an analysis of the Honduran election

November 5, 2013

Personal reflections on Roatán, the Bay Islands and the Garífuna

November 4, 2013

So what’s the big deal about Honduras’s election?

November 3, 2013

Toncontín blues: Of airports and infrastructure in Honduras

November 3, 2013

Chart of the day: Central American GDP per capita

October 29, 2013

![]()