It’s not surprising, perhaps, that as the votes from Guinea’s October 11 presidential election are counted, incumbent Alpha Condé is leading with nearly 60% of the vote. ![]()

This is a country where it took six years to schedule a single set of elections for the country’s parliament.

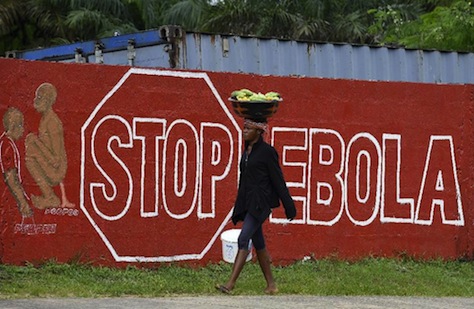

The west African country is the first of three Ebola-stricken countries to hold an election since the epidemic ended late last year, and Condé, who won election in 2010 in the first democratic vote in Guinea’s post-independence history, was expected to fall somewhat short of a majority — forcing a runoff with his 2010 rival, Cellou Dalein Diallo, an economist and, for a brief time, prime minister under Guinea’s 24-year dictator, Lansana Conté. Only weeks before the election, Guinea marked its first Ebola-free week since the height of the crisis.

As it became clear throughout the week that the vote count will show Condé with an unassailable lead, Diallo has withdrawn from the contest following last Sunday’s election, citing fraud and a generally unfair campaign environment. Diallo’s allies had previously called for a delay in the elections, citing delays in providing voting cards to all potential voters, and Diallo himself called for a re-run in the immediate aftermath of the voting, alleging ballot stuffing and other fraudulent practices. EU observers, for what it’s worth, declared the elections sufficiently valid so as not to require a revote, even while analysts are doubting whether sub-Saharan Africa is necessarily becoming more democratic.

* * * * *

RELATED: West Africa’s Ebola crisis is as much

a crisis of governance as health

RELATED: Guinea struggles to schedule elections after opposition protests and six years of delay

* * * * *

With 11.75 million people, Guinea is a fast-growing country in west Africa, though it’s struggled since independence. The first country to break with French colonial rule, it had no democratic institutions to speak of until five years ago. Its first leader, Ahmed Sékou Touré, ruled as an autocrat for a quarter-century, and the country held its first election in 2010 following a two-year military transitional government that took power after Conté’s death. Continue reading Guinea struggles with election amid few truly democratic institutions