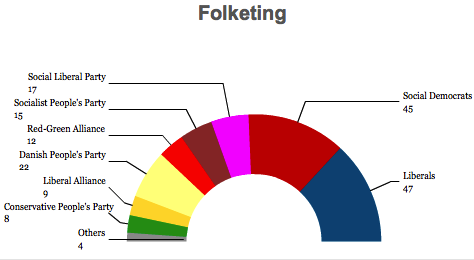

In an election race that finished as closely as polls predicted, the broad center-right ‘blue’ bloc won 90 seats in Denmark’s Folketing, while the broad center-left ‘red’ bloc of prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt won just 89.![]()

Though that’s a stupendous effort for Thorning-Schmidt and, especially, her Socialdemokraterne (Social Democrats), which actually gained seats and finished with the highest share of Denmark’s many political parties. Since winning the 2011 election, polls consistent showed Thorning-Schmidt’s coalition trailing by double digits, so the election result represents something of a comeback for the Danish left in general and for Thorning-Schmidt in particular.

Her coalition partners didn’t manage as well, though, so Thorning-Schmidt will not serve a second term as prime minister and, despite her success, she stepped down as the Social Democratic party leader after the narrow loss.

* * * * *

RELATED: How Helle got her groove back in Denmark’s snap election

* * * * *

The center-right’s victory means that former prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, the leader of Denmark’s chief center-right party, Venestre, will once again return to power as head of a minority government, according to reports on Sunday. But Thursday’s vote is still something of a Pyrrhic victory for him, because his party finished with 19.5% of the vote, about 7% less than the Social Democrats and, more significantly, about 1.5% less than the anti-immigration, eurosceptic Dansk Folkeparti (Danish People’s Party).

While the DF’s leader Kristian Thulesen Dahl (pictured above) didn’t demand the premiership, he will now be the chief driver of Danish government. Rasmussen is an amiable figure, but he’s been damaged by an expenses scandal and his party is now returning to power, despite the fact that it lost more seats (13) than any other party in the Folketing. Though the Danish People’s Party will conceivably his government from outside any formal coalition, there will be no doubt that Thulesen Dahl’s agenda — a populist approach to pensions and welfare spending, rolling back immigration (especially Muslim immigration), and chipping away at the free borders of the European Union’s Schengen zone (the party wants Denmark to leave the Schengen zone altogether) — will figure high on Rasmussen’s priority list. It also means that the Danish government will strongly back British prime minister David Cameron’s push for EU reform, in advance of a 2017 referendum on British membership in the European Union.

More thematically, the success of the Danish People’s Party is part of a broader story about the rise of the alternative right across Europe, especially throughout Scandinavia in recent years:

- Norway’s anti-tax Framskrittspartiet (Progress Party) had a breakthrough performance in the 2009 election, winning 22.9% of the vote and becoming Norway’s second-largest party. In the September 2013 elections, it still won 16.6% of the vote, and its leader, Siv Jensen, serves as finance minister in Erna Solberg’s conservative minority government.

- Last September, Sweden’s far-right Sverigedemokraterna (Sweden Democrats) won 12.9% of the vote to become the third-largest party in the country. Just one month into the premiership of center-left prime minister Stefan Löfven, the Sweden Democrats caused a political crisis that brought the country to the brink of a fresh snap election.

- The similarly far-right Perussuomalaiset (PS, Finns Party) finished in third place in Finland’s elections with 17.6% of the vote in March 2015, and its leader, Timo Soini, a skeptic about future Greek bailouts, is now Finland’s foreign secretary.

It’s clear that the message of parties like the DF resounds with a significant portion of the northern European electorate, including in the United Kingdom and France, and immigration — from both inside the European Union and from Muslim emigrants from beyond — has a growing resonance. Even Thorning-Schmidt’s Social Democrats felt like they needed to take a harder line on the issue, with advertisements proclaiming that Danish immigrants should be working.

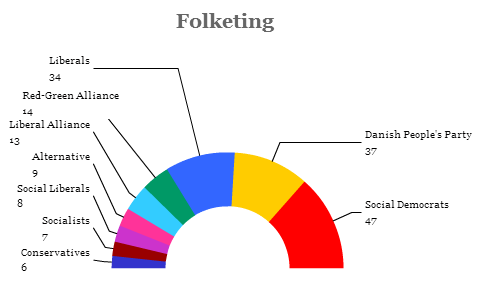

It’s not clear yet which parties Rasmussen will seek to form his minority government, but Thulesen Dahl’s tone seems to indicate that it won’t include the Danish People’s Party. But Rasmussen’s Liberals have just 34 seats — with support from the Liberal Alliance (13 seats), the Konservative Folkeparti (Conservative People’s Party (six seats), it gives Rasmussen just 53 seats.