Photo credit to Jari Laukkanen/Suomenmaa.

Photo credit to Jari Laukkanen/Suomenmaa.

As expected, the liberal Suomen Keskusta (Centre Party) won the largest share of the vote in Sunday’s parliamentary elections in Finland after a campaign dominated by Finland’s flagging economic recovery.![]()

That means Juha Sipilä, a former telecommunications executive who entered Finnish politics just four years ago, will become the country’s next prime minister, and he will prioritize an agenda of economic reform that includes personal and business tax cuts, further budget-trimming and steps designed to increase the competitiveness of Finnish industry.

The Centre Party led Finland’s government most recently between 2003 and 2010 under former prime minister Matti Vanhanen, who also emphasized tax cuts and promoted innovation — Vanhanen’s government was the first in the world to introduce a legal right to broadband internet. Olli Rehn (pictured above), who from 2004 to 2014 became the European Commission’s chief official for economic and monetary policy, won a constituency in Helsinki to return to the Finnish parliament, where he’s expected to play a leading role in the new government — quite possibly as Finland’s next finance minister.

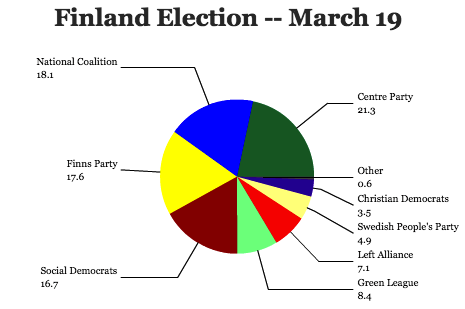

But the Centre Party’s narrow victory wasn’t the most convincing — it only defeated the governing center-right Kansallinen Kokoomus (National Coalition Party) by just over 3%. Another two parties, the far-right Perussuomalaiset (PS, Finns Party) and the center-left Suomen Sosialidemokraattinen Puolue (SDP, Social Democratic Party) weren’t far behind.

Each of Finland’s four major parties won between 17% and 21% of the vote, hardly a ringing endorsement for anything other than the traditional moderation and consensus that has marked past Finnish governments. For now, the Centre Party’s victory will end talk of Finland’s potential accession to NATO, a position that outgoing prime minister Alexander Stubb favored and that Sipilä (along with most Finns) opposes.

* * * * *

RELATED: Who is Juha Sipilä?

The man who wants to become CEO of Finland, Inc.

* * * * *

But it also means Sipilä’s government will almost certainly depend on the Finns Party in some form. Throughout the Finnish election campaign, that has caused trepidation throughout Europe for two reasons. First, the eurosceptic far right will now hold the balance of power in Finland, a scenario that’s becoming increasingly common in the Nordics as anti-EU nationalists continue to gain support throughout all of Europe. Second, because the Finns Party are opposed to future Greek bailouts, Finland’s new government could complicate efforts to reach a new deal on Greece’s financing that will allow it to remain in the eurozone.

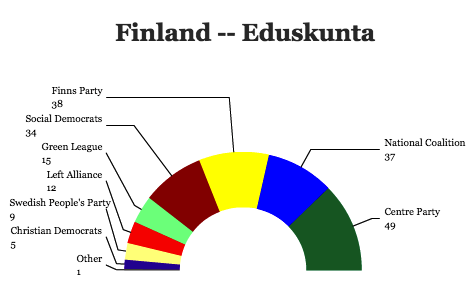

Perhaps the biggest surprise in Sunday’s vote was the strong showing of the Vihreä liitto (Green League), which gained five seats (for a total of 15) in the 200-member Eduskunta, the unicameral Finnish parliament.

Sipilä hopes to avoid the same unwieldy coalition that hampered the National Coalition-led government since 2011, first under Jyrki Katainen and under Stubb for the past 10 months after Katainen joined the European Commission (where he currently serves as vice president for jobs, growth, investment and competitiveness). Katainen was disappointed in his plan to enact deeper reforms, in part because he was forced to balance an unwieldy six-party coalition that included not only the center-right National Coalition, but the Social Democrats, the Green League and the Left Alliance (Vasemmistoliitto).

Sipilä starts out with less than half the seats he needs for a coalition. If Sipilä includes the conservative Kristillisdemokraatit (Christian Democrats) and the Svenska folkpartiet i Finland (Swedish People’s Party), a small party devoted to the interests of Finland’s Swedish-speaking population, he’ll have just 63 seats.

That means he’ll need at least one more major party. With the support of the Finns Party, however, Sipilä would just barely reach a 101-seat majority. Despite the economic liberalism of Rehn and Sipilä, the Centre Party has a traditional agrarian wing that’s far less enthusiastic about austerity and liberalization, so Sipilä will likely prefer at least two additional major parties that can give the new government a looser margin of error on key legislation.

All things considered, Sipilä wants (a) to lead a center-right government with a pro-business agenda, (b) do so with a coalition that’s nimble enough and ideologically consistent to achieve that agenda, (c) a majority that’s substantial enough to enact policy, and (d) on balance, a government that doesn’t include parties seen as radical or destabilizing within the rest of the European Union.

On the numbers of Sunday’s election, Sipilä simply cannot achieve (a), (b), (c) and (d). If he includes left-wing parties or too many disparate voices into the coalition, he’ll risk his agenda. If his majority is too narrow, he’ll be held captive by holdouts in the Centre Party or otherwise. The only way Sipilä can avoid those outcomes is to make a deal with the Finns Party to support him, either formally in government or informally outside a coalition.

Given Sipilä’s body language throughout the campaign, and his prior statements that he ‘can do business with’ the Finns Party, it’s not unreasonable to assume that (a), (b) and (c) are more important to Sipilä than (d).

That will put Timo Soini, leader of the Finns Party, in the driver’s seat on the country’s policy towards Greece, and it means that if the Finns want to make a stand on Greece, they can hold up any potential new debt deal, including a possible third bailout subject to ratification by Finland’s parliament. Understandably, that outcome will cause anxiety from Brussels to Athens.

It undoubtedly makes Greece’s path to stability a little more difficult, heightens the importance of Finland (and Katainen and Rehn) in Eurogroup negotiations, and it gives Greece’s creditors, on the whole, more leverage to demand concessions from Greek leaders.

But in a scenario where Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras and German finance minster Wolfgang Schäuble reach an agreement on Greek debt, it’s hard to believe that Sipilä will be willing to tie his legacy to forcing Greece out of the eurozone, even if that forces a new coalition or, possibly, snap elections.